In the media, measures of attention are big business. They determine what you can charge your advertisers and how seriously people take your outlet. In commercial TV and radio, stars and shows live and die by their figures.

But the figures are often far from perfect. Of the many official ways audiences and reach are measured in the Australian media, a range of methods and biases can throw things out. Some rankings are freely available to anyone who wants to look them up. Others are kept in-house, or sold to subscribers for a fee. Some you can take at face value, and others, well, it doesn’t hurt to be aware of their flaws. Here are the most common measures of audience used by media companies, and what you should make of them.

The small screen

The TV figures are some of the most important of all, partly because of how often they come out and how (relatively) robust they are. On the small screen, how many people are watching is measured minute by minute. TV execs can pore over the previous day’s ratings from early the next morning. Things that don’t rate well don’t tend to last.

The company that wields so much power over the small screen is OzTAM (short for Australian Television Audience Measurement), which is owned by the Seven, Nine and Ten networks. It installs measuring hardware on the televisions of several thousand homes (5250 are participating in the free-to-air measurement system in 2017) and simply measures what that sample are watching, night by night, minute by minute, demographic by demographic. You can get access to them by subscribing (a small number of industry players pay millions a year to do so), but they’re not hard for media reporters to get their hands on for free, which is why you see them reported on in so many places (including Crikey).

If the sample is representative (OzTAM weights the survey so it is representative of the broader population), then the measures are statistically robust, if not perfect — it is, after all, an extrapolation on a smallish sample. But television is being disrupted, and that’s starting to show. Many young people no longer own televisions. Australians of all ages watch things online rather than turning on the TV set. Streaming figures exist, but not in a centralised place you can check the next day. Many are tracked internally by the various broadcasters, and not publicly released.

[Playing in traffic: the dirty tricks publishers use to boost online views]

Another problem with streaming is that people stream TV when it suits them, not the moment it’s available. The overnight TV ratings are easy to understand and report on, but for many types of shows, they do not capture total viewing. For dramas in particular, the TV ratings are less than robust. Last year, Crikey pointed out that the ABC’s Cleverman, a new indigenous sci-fi drama, got killer reviews, but poor ratings. But our analysis didn’t include iView views. We did ask about them, but the ABC doesn’t routinely release such figures, and it didn’t release them to us.

Multi-channelling has also complicated things — some networks run shows on more than one channel at the same time, which can provide an audience boost. Still, for all their faults, the OzTAM figures are timely, detailed and relatively transparent.

Don’t touch that dial

The radio ratings are just as closely watched as those in television. But unlike their cousins in television, radio execs have to wait.

A few times a year, thousands of people across Australia are given diaries and told to fill them out over a given week. Every radio ratings survey averages out responses over a few weeks, and GfK, which since 2013 has complied the ratings for industry body Commercial Radio Australia, carefully controls the age and geographical distribution of those selected.

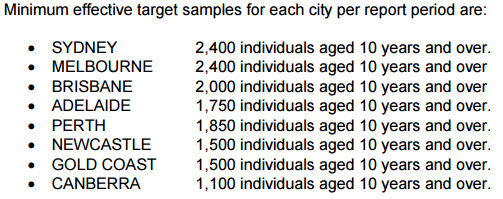

Minimum sample sizes for each city, from GfK’s explanation of how it does the radio ratings.

Four in five of those who participate in the survey are given paper diaries and told to fill them out every day with their listening habits. The final 20% are given digital ones. At the end of every survey period, the figures for each city are collated and averaged out over a few weeks, to give an average listenership number for each station by time block.

Of course, as with any survey-based system, listeners are likely to remember the most popular stations and time-slots when they fill out their diaries. Because of this, some have argued the diary system helps preserve the radio status quo.

Inky fingers …

For newspapers, print circulation relies on average daily sales records as provided by participating newspapers. These are released four times a year by the Audited Media Association of Australia, and list paid distribution. That also includes discounted copies to airports, schools and hotels, which are broken out separately. For a while, there was a push to count digital subscriptions in with the daily papers, to more accurately reflect a paper’s total subscriptions base. But this never got much traction. Only a handful of papers revealed their digital subscriber numbers, and at its annual results this year, Fairfax said it would no longer provide its digital subscription numbers for The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age.

It had never given digital subscription figures for the Financial Review. Likewise News Corp has very selectively provided digital subscription figures to Nielsen — and recently, News Corp executive Damian Eales joined Fairfax’s Greg Hywood in saying the figures weren’t really what advertisers were after. “The reality is that media buyers and advertisers aren’t interested in circulation. They plan media based on the audience that reads a paper, not the number of papers printed,” he told the Oz.

Just before Christmas, the nation’s three major magazine publishers pulled their titles out of the Audit Bureau, arguing total audiences, including digital, were a far more important metric to advertisers. That will mean fewer bad news stories for the magazine industry — for a time at least.

… But isn’t print dead?

That’s an argument newspapers make as well, though, so far, none have entirely pulled their print editions out of the circulation audit. But they have emphasised a new, preferred metric. Total print reach is combined with digital reach in a newish monthly measure called EMMA, owned by industry body NewsMediaWorks (formerly Newspaper Works — it changed its name to better reflect the times last year). In EMMA’s favour, the figures are released monthly and are publicly available on its website.

The EMMA survey relies on after-the-fact surveys of around 50,000 people who participate in a panel, asking them what they’ve read for more than two minutes over the past month. The sample is massaged to be broadly representative, in much the same way political polling is. Like radio ratings and other “survey” measures of readership, there’s a potential bias in this methodology — people remember the more popular brands more easily than smaller ones.

[‘Magical’ newspapers take a hammering in circulation figures]

EMMA controversially assumes every print title is read multiple times, even if it is only purchased once. According to the EMMA survey, nearly 1 million people (942,000) read the Australian Financial Review in print in October 2016. This for a paper that sells less than 50,000 copies a day, according to its circulation figures. In magazines, Woman’s Day had a print audience of 2.8 million in the same month — even though, according to the September quarter circulation figures, it sold less than 250,000 copies a month (every copy would have to be passed around more than 10 times to get the print readership figure EMMA’s surveys find).

But print is only one part of the EMMA survey: to arrive at a total masthead readership figure, it combines the print with the Nielsen/IAB audience digital estimates.

That brings us to the final measure of audience, which is digital reach. The gold standard for news outlet reach in Australia are the monthly Nielsen digital news figures, which are just one category of several types of websites measured by Nielsen.

The system is somewhat complex and was refined last year to gather more data from mobile and tablet users. Data is collected first through the publishers themselves, which allow Nielsen to implant traffic-measuring add-ons to their websites. More data is collected from panels of smartphone and tablets users, who might browse websites only through dedicated apps from publishers, as well as PC users, which are fused together and then “calibrated” from figures obtained from the tagged websites.

Of course, all digital traffic systems are vulnerable to manipulation. Popups, auto-play videos and even traffic bought through bots can all help keep the page-views up if they ever dip. Though reputable publishers wouldn’t want to rely on such tactics too much — advertisers see through them eventually.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.