The media briefly got itself into a tizz this week over some new data released by federal Education Minister Simon Birmingham.

“One-third of Australian students won’t graduate within six years,” The Sydney Morning Herald reported. The ABC and The Australian also carried the story.

The data made for some nice headlines for Birmingham, who is seeking to position himself as a kinder and gentler reformer in a portfolio that troubled his predecessor, Christopher Pyne.

“We’ve heard too many stories about students who have changed courses, dropped out because they made the wrong choices about what to study, students who didn’t realise there were other entry pathways, or who started a course with next to no idea of what they were signing themselves up for,” Senator Birmingham told The Australian.

Positive coverage for a Coalition is rare these days, even in The Australian, so hats off to Birmo for his media coup.

The only problem? The story is a massive beat-up.

As so often in higher education policy, a flawed metric and lazy journalism have combined to paint a picture at odds with reality.

If you examine the Department of Education data, which no one in the mainstream media seems to have bothered to do, you can see why.

The top level figure of 66% completing by six years is not the headline figure from the report (this figure instead comes from Birmingham’s media release).

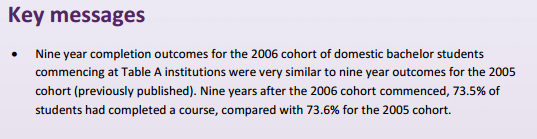

In contrast, the department’s study highlights completion rates after nine years. The figure here is rather better: 73.5 %.

I’ve screen-shotted the executive summary of the report. The nine-year figure is the top dot point. You would have hoped that the media could actually look at the primary source they were reporting on.

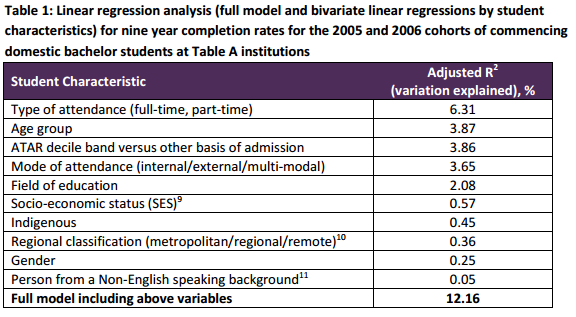

The report goes on to attempt a regression analysis of the reasons that might explain drop-out rates for those students who don’t go on to complete their courses.

It’s not a particularly strong regression. The best explanation for why students don’t complete is their type of attendance (full time or part time). But this factor explains just 6.3% of the variation.

As Curtin University’s Tim Pitman notes in The Conversation: “The report acknowledges that the method of analysis may overstate the strength of the relationship between particular factors and completion, and that a range of factors are ‘less amenable to measurement or unmeasurable’. However, these important caveats, by and large, do not make it into the media releases.”

Universities Australia’s Catriona Jackson defended the sector this week. She told the ABC’s Julia Holman that the attrition rate is actually third best in the OECD. “There are a number of reasons people don’t complete degrees and it would be very, very strange if we had 100 per cent completion rates, nowhere in the world does.”

Jackson pointed out that completion rates had stayed steady, even as the higher education system has massively expanded. “They’ve been pretty consistent and pretty good while we’ve opened up the system to people of low socio-economic backgrounds, people from indigenous backgrounds, people from rural and remote areas, we’ve welcomed everyone in and completion rates have not changed. That is an extraordinary achievement for the higher education system, and for those students most importantly.”

The media also used the data from the Education Department report to construct league tables. The league tables put the University of Melbourne on top, and Charles Darwin University on the bottom. This is more junk data, based on sloppy reporting.

As with league tables for primary and secondary schools, what they really measure are socio-economic advantage. The top universities tend to harvest the wealthiest and most educationally advantaged students; these are the ones most likely to go on to graduate. Universities in regional Australia draw their cohort from a radically poorer and more disadvantaged population. These students face multiple barriers to completing their studies, and so fewer of them complete.

Indeed, one conclusion you could make when looking at the socio-economic factors underlying university completion is the same one that the Gonski panel made when looking at similar data for the schools system: that if we want to improve outcomes, we need to spend more money on the most vulnerable students. Strangely, that was not the argument put forward by Simon Birmingham.

But there’s an even bigger problem with the focus on completion, and that’s the instrumentalist idea that the only thing that matters in education is gaining a qualification.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but this is a rubbish idea. Education matters for many reasons. Few of them boil down to the piece of paper you get at the end of your degree.

Is the effort put in by students to courses they don’t complete wasted? Surely not.

Higher education is structured into discreet lessons and units. If you studied Indonesian or philosophy or mechanical engineering for a couple of years and drop out, do we really think that you will mysteriously forget everything you’ve just learned? If you turn up to classes, if you turn in assessment, if you take the time and effort to engage with a difficult academic field, then you have plainly gained something from your studies, even if you don’t graduate with any degree.

Students drop out of courses for all sorts of reasons: to care for family members, for reasons of illness, or because their priorities have changed. Some do drop out because of poor teaching or because the course is not right for them. But some also drop out to enter the workforce, an outcome we can assume Simon Birmingham would support.

So why is the government so keen for students to complete their courses? A paragraph buried halfway down The Australian’s write-up explains it nicely.

“Senator Birmingham has also asked [the Higher Education Standards Panel] panel to investigate trends in student completion rates and to consider how universities can be helped to arrest attrition rates and support enrolled students through to course completion.

“Doing so would help the government claw back the amount of debt now not expected to be repaid, which is accruing under the FEE-HELP student loan scheme.”

Ah yes, clawing back debt for the federal budget. Now there’s something that any Coalition minister can understand.

When I started a science degree in 1979 we were told by a lecturer to “look at the ppl on either side of you, out of the three of you only one will be here by the end of the year”. They were right about me, I wasn’t there. But I finished a Law degree, and three Masters later. People starting Uni are often 17 with no experience. They need to try things out, find what’s best for them. That was in the days of fee-free Uni. If only 1 in 3 finishes within 6 years that’s a higher rate than in the past. It may not be a good thing. Students not wanting to accrue massive debts may be sticking to things when they shouldn’t, or just simply so many have to work long hours that it’s taking them longer to finish ( since after 7 years the figures show 75% will have finished. After 8 years maybe it goes up to 90%, who knows?). Just another example of this hopeless govt trying to divert attention from THEIR failures. Welfare recipients, aged pensioners, unemployed, last vulnerable group- students, so they’re going after them. Who voted for these people?

Agreed. However, it also suits Uni’s financially to have 1st year undergrad’s packed to the rafters, while knowing they will decimate those numbers going into 2nd year. To achieve so many 1st year applications, Uni’s run Foundation courses for those who never made the appropriate ATAR. It’s mind boggling to see students who attained an ATAR of <50% in their HSC (thus ineligible to attend Uni), a year later achieving a 92% equivalent score after completing one of these Foundation courses. The stat's on the overall success rate of this the particular demographic would be very interesting.

Not mind-boggling at all. Entrants to that course know why they are there and are taught what is needed in the way it is needed by people who know how to teach it — unlike lockstep and forced choice in schools. It is not the improvement that boggles the mind, it is the waste of talent that had preceded it in their school experience.

I totally agree with the sentiment in this article, but there is one part that doesn’t make sense. You state: “The top universities tend to harvest the wealthiest and most educationally advantaged students; these are the ones most likely to go on to graduate.” But earlier, you used Table 1 from the report to argue your case, and this table shows that SES only accounts for 0.57% of the dropout rate. What am I missing?

That model should not be taken seriously: with an adjusted R2 at 12.16% what it is measuring is just noise.

I think your observations are correct. But Charles Darwin University has high proportions of part time, mature and external students.

Simon Birmingham is under the impression that universities are degree factories. Fair enough, as most modern university management also sees things that way, and seeing as failing a student may see less income, it tends to be discouraged.

Simon Birmingham, like Pine before him, is just massaging figures to support his own agenda. Lazy, feckless, career politician. And his point would be, of course, that he reckons fewer people should be going to Uni, and they should be those who can afford to pay. So much wrong with that. As the article says (kind of), University is a unique and immensely valuable experience even if you don’t finally end up with a degree. But the figures seem to be saying that more people do than don’t, eventually. So Birmingham, like the rest of this government’s front bench is just completely out of touch.

I know I had a unique and immensely valuable experience, 50 years ago, and despite that I got a degree as well!

“I know I had a unique and immensely valuable experience, 50 years ago, and despite that I got a degree as well!”

Nicely put. Same with me, and I never practised in the field where I had “qualified”. In a full working life, I did a lot of good I believe — using only the most general learning from my Honours degree. Would not change one bit of that.

Speaking of education, I think you mean ‘discrete lessons’

Thanks Ben for doing the leg work for this piece and giving us a realistic view to counter Mr Birminghams fantasy land. I did not complete the last 10% of a post graduate qualification 35 years ago – changed jobs, new family, etc, sometimes kicked myself, but have used the knowledge gained, and expanded on it, in my working life. Much gained, nothing lost.