News from New Zealand confirms what data from Australia and Ireland has strongly suggested: cutting taxes on corporations leads to sharp economic deterioration; increasing company tax improves things considerably.

The annual report from the Kiwi tax office and the latest GDP growth data come at an awkward time for Australia’s Treasury and Treasurer Scott Morrison. Morrison is insisting the path to jobs and growth is to cut taxes on companies and the rich. Treasury has just published an academic paper, which tries to bolster this. It claims the New Zealand experience supports slashing both company taxes and government outlays.

The latest trans-Tasman data provides a compelling counter argument — one which Treasury should heed seeing it brought up the comparison in the first place.

Well, not Treasury directly. It came up in a “research” paper published by Treasury, written by anti-Labor academic Tony Makin. The paper has copped negative reviews here at Crikey, the SMH, The Canberra Times and elsewhere.

Makin claims:

“… the nature of Australia’s fiscal stimulus was misconceived because it emphasised transfers, unproductive expenditure such as school halls and pink batts, rather than tax relief and/or supply side reform, as occurred for instance in New Zealand where marginal income tax rates were reduced, infrastructure was improved and the regulatory burden on business was lowered.”

Superficially, Makin seems to have an argument. It is true Australia increased taxes on companies and spent up big on infrastructure from 2008 to 2010. It is true that New Zealand cut company tax in 2008. It is also true that Australia’s economy is now close to the worst-performed in the world, and New Zealand’s is one of the best.

So an open and shut case? Not quite. The missing information in the Treasury paper — and in Morrison’s understanding, it seems — is the dramatic policy shifts that took place in New Zealand in 2011 and in Australia in 2013. We need to examine carefully what happened in both countries before and after those major policy about-turns. We now can.

From 2008 until 2013, Australia undertook hefty stimulus programs funded by reserves and moderate borrowings. This required significant budget deficits — between 1.2% and 4.2% of GDP.

Taxes on corporations were significantly increased. For those five years, the company tax take averaged 21.5% of total taxes collected. That was well above the 19.6% for the previous seven years. As a proportion of taxes on individuals, company tax collected rose to 44.6%, compared with 40.9% for the previous seven years. (Note we are looking at actual collections. Nominal tax rates are meaningless when evasion is rampant.)

The outcomes? Not just the best-performed economy in Australia’s history or in the developed world, but in the entire world:

- hours worked per adult per month: 86.5;

- median wealth per adult: US$219,505 (highest in the world);

- economic freedom Heritage score: 82.0 (highest in the OECD);

- near optimum interest rates: 2.5%;

- budget deficit: $18.8 billion (down from $43.4 billion the previous year);

- gross debt: $270.0 billion;

- value of the Aussie dollar: 92 US cents; and

- quarterly GDP growth: +0.6% in a 10-quarter positive streak.

That is despite the lingering GFC, with six OECD countries still in recession.

Substantial policy shifts followed the 2013 election, notably much less company tax collected. For the four years 2014 to 2017 (the last year is projected), company tax fell to 19.3% of total taxes. As a proportion of individuals’ tax, it plummeted to 36.8%.

What then happened to outcomes? All deteriorated badly. Australia now has:

- hours worked per adult per month: down to 84.9;

- median wealth per adult: down to US$162,815 (ranked third in the world);

- economic freedom Heritage score: down to 80.3 (now third in the OECD);

- interest rates: tumbled to 1.5%;

- budget deficit: more than doubled to $39.6 billion;

- gross debt: up 77% to $476.8 billion;

- value of the Aussie dollar: down to 75.6 US cents; and

- quarterly GDP growth: -0.5%.

That is despite the steady global recovery, with no OECD country now in recession.

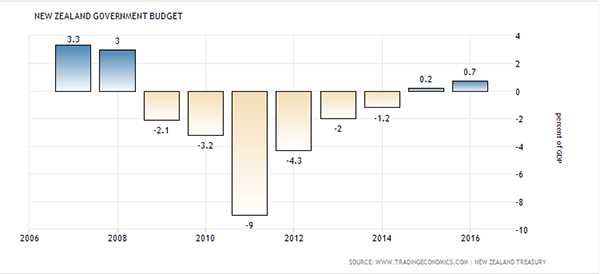

New Zealand appears to have observed Australia’s extraordinary success through the GFC and changed its course almost diametrically in 2011. It borrowed extensively, expanded the deficit to a whopping 9% of GDP — close to the world’s highest that year — and raised taxes on companies.

For the five years 2012 to 2016, the company tax take averaged 19.0% of total taxes collected. That was much higher than the 17.4% for the previous five years. As a proportion of taxes on individuals, company tax went up to 39.7%, compared with just 34.8% for the previous five years.

So New Zealand did, in 2011, pretty much the reverse of what Australia did in 2013. The results? Jobs and growth! The Kiwis now enjoy:

- unemployment: 4.9%, down from 6.2%;

- GDP quarterly growth is now 1.1% in a streak of 14 positive quarters, compared with -0.2% and -0.6% for the last two quarters of 2010;

- annual GDP growth is 3.5%, almost double Australia’s 1.8%;

- median wealth per adult is now US$135,755, ranking fifth in the world, up from $61,971, ranked 17th, in 2010;

- economic freedom Heritage score: 81.6, highest in the OECD, having overtaken Australia and Switzerland in 2015;

- budget surplus is now 0.7% of GDP compared with a deficit of 9.0%; and

- gross debt NZ$87,777 million, below the level of the last two years and reducing steadily now the budget is in surplus.

A 2014 paper by Tony Makin made the same points as this latest one about stimulus spending — bad — and company tax cuts — good. The previous Treasury secretary Martin Parkinson emphatically debunked Makin’s assumptions, methodology and conclusions. Looks like Parkinson was correct.

BCA please take note.

There isn’t a question or theory in economics that cannot be evaluated with a $5 calculator and cui bono?

Well done Alan. If only we lived in a world where facts mattered, at all.

Any chance this article will find it’s way into the OZ or FR?

Alan, my right-wing mate tells me that New Zealand couldn’t have borrowed to stimulate because international lending was close to frozen. He asserts we could stimulate back then because we had virtually no debt.

How can I counter? I don’t know enough about that.