Confounding the familiar government narrative of reckless spending binges by Labor, the Coalition actually has the record of greater profligacy when it comes to showering billions of dollars of taxpayers’ money on external consultants.

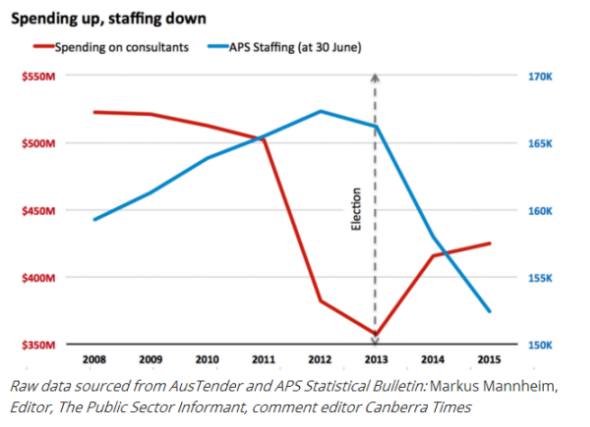

When John Howard became prime minister, he axed 30,000 employees from the public service. But in his second and third terms in office, public service numbers rose again. They continued to rise under Kevin Rudd’s Labor government, only to taper off during Julia Gillard’s tenure and drop sharply under the present Coalition government.

Consultants’ fees, however, after rising under Howard, eased back under Rudd before falling by more than 30% under Gillard. They rose again the moment Tony Abbott assumed office, and have continued to rise, albeit more modestly, under Malcolm Turnbull.

How will government look in 20 years?

Such is the pervasive influence of corporations and consultants over government and the de-skilling of the public service (as evinced by the recent slew of IT debacles) that Australia appears headed down the road to full-blown corporatocracy.

If they rely further on external parties for expertise and policy advice, governments — both state and federal — are likely to be emasculated, entirely laid at the whim of private vested interests.

With no expertise, let alone pricing power in negotiating external fees for expert advice, there will come a heavy cost to the public.

The devastating failure of Australia’s energy policy and spiralling prices for gas and electricity throw up a potent case in point.

It was recently reported that the big four accounting firms — PwC, EY, KPMG and Deloitte — picked up $2.6 billion over the past 10 years for writing reports. That is from the federal government alone, to just the four top firms. They may have earned that again consulting to the states, though state disclosure is poor.

The crowning jewel in this cuff-linked fee-fest was a payment of almost $10 million, or $75,000 a page, for PwC to write its report on the future burden of welfare costs. This was the work that presaged the government’s strike on social security late last year and the ensuing Centrelink imbroglio.

Consultants’ reports deliver a licence for political action, an imprimatur. In light of the lavish fees, though, their authors can hardly claim to be “independent experts”.

[Public service stuck in the hole Abbott dug for it]

Why could the Treasury not have penned this report? Why not the Productivity Commission? Surely, as bureaucrats, they are more independent, not susceptible to the tow of large corporate clients on the other side of a Chinese wall.

Is government captive to big business?

To put it crudely, many observers put the extravaganza of consultants’ fees down to “butt-covering”. This is just a ploy to lay the responsibility for political decisions, in case they go awry, at the feet of an external party. External reports can “test the water”, and can be tossed out without recrimination. They are so often a terrific waste of money.

There are two issues to consider then: one, the encroaching influence of private power over public policy; and two, the enormous expense to taxpayers in private firms penning reports that government departments and agencies could just as easily prepare.

Further to this rising sway of vested interests, there is also the incursion of corporate power in government in a physical way, via secondments.

Leading law firms, accountancy firms and banks often have executives spend time with a regulator or government department, but secondments are poorly, if ever, disclosed.

Then there are the “revolving doors” between industry and government: the passing of politicians, political staffers and the likes of mining lobbyists between industry, advocacy bodies and the public service. Governments are infested with industry people with vested interests.

As is the case with secondments, there is little in the way of transparency or decent policy in the arena of staff movement despite the inevitable influence it exacts over government policy. Not to put too fine a point on it, state and federal governments are infested with industry people whose influence on policy is undeniable.

The multinationals’ hidden hand

While consultancies, political donations, secondments and staff movements magnify corporate influence over government, an equally sinister trend is playing out in the world of multinational corporations.

Many observers of the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership have expressed alarm that the fine print to the TPP draft agreement contains Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) clauses. These are mechanisms that allow corporations to sue governments by claiming a change in a nation’s policies has adversely affected their business.

Indeed, more than 120 cases have been filed internationally under various “free trade” agreements. Water and waste management giant Veolia sued the government of Egypt for lifting the minimum wage. Canada is being sued for a ban on fracking. Germany was sued for its phasing out of nuclear power. All these actions were taken under ISDS clauses in free-trade pacts …

*Read the rest at MichaelWest.com.au

“Read the rest at MichaelWest.com.au” . . . . . no offence Michael, but invitation is equivalent to “slash my taxpayer wrists here . . . . ” re ISDS fine print ‘pay-offs’ etc etc!!!

Too right Michael.

Was having the conversation with a colleague this week about how the death of the public servant and the rise of the ‘consultant’, doing the same job for twice and three times the price, (and more). The loss of expertise in the public sector is now biting hard, and as much as it used to be infested with incompetents (better placed there then on welfare) it was also populated with serious and clever people who carried all the work.

Watch the debacle when Land Titles is sold off. There will be big time recriminations with that one. Some have already happened as they have rid themselves of public servants who knew what they were doing.

In Queensland the NSW privatization of the titles office is being watched with open mouths. Has no one understood that one of the great problems of Russia is not being quite sure who owns the land on which you wish to build your business?

Well done, Michael. What is the driver behind this purblindness to the obvious?