Some recent data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) points to significant progress over the last 20 years in the treatment of cancer in Australia — and allows us to compare how we perform internationally in treating one of our most common killers.

Cancer is responsible for around three in 10 deaths in Australia and, according to the AIHW, will kill over 47,000 Australians this year. Lung cancer is the biggest killer for both men and women, followed by prostate cancer for men and breast cancer for women, then colorectal cancer. But our prospects for surviving a cancer diagnosis have improved significantly since the 1980s; your chance of surviving five years after a cancer diagnosis in the mid-’80s was, on average, 48%. In the period 2009-13, it was 68%. And that figure increases to over 80% if you survive 12 months after diagnosis.

The most survivable cancers are testicular cancer (98%), thyroid cancer (96%) and prostate cancer (95%) but a diagnosis of mesothelioma (6%) or pancreatic cancer (8%) remains devastating. Breast cancer has a survival rate of around 90%, but lung cancer is less than 20% — although for younger people it’s over 60% and then falls quickly for older people; similarly, survival rates for cervical cancer are very high (91%) for young women, but fall dramatically with age. Children and young people also tend to suffer from brain cancer and leukaemia more compared to adults.

The cancers with the greatest increases in survival rates were prostate cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and kidney cancer — for all of them, survival rates have increased at least 20 percentage points since the 1980s. Survival rates for bladder cancer have actually fallen, but so has the incidence — while it’s still in the top 10 cancers for men, incidence has fallen by nearly half since the 1980s.

Thyroid cancer, however, is being diagnosed far more frequently — an increase of over 350% since the ’80s (due, the AIHW suggests, to new diagnostic techniques and technology); the diagnosed incidence of liver cancer has increased four-fold; kidney cancer has almost doubled, as has melanoma, while breast cancer diagnosis has increased around 50%; cervical cancer incidence has fallen by around 50% due to screening for pre-cancerous abnormalities. While the incidence of cancer rises with age, it’s in your 50s that the chances of diagnosis really accelerate, particularly among men. Melanoma is the most common reason for a cancer-related hospitalisation, followed by prostate cancer for men and breast cancer for women.

Cancer doesn’t just distinguish between older and younger people, but between socioeconomic groups. Low socioeconomic groups are more likely to suffer from lung cancer and cervical cancer. And indigenous Australians are more likely than non-indigenous Australians to be diagnosed with liver cancer (2.8 times as high as non-indigenous Australians), cervical cancer (2.2 times) and lung cancer (2 times). Poorer access to health services also means indigenous people also have higher rates of unknown primary site cancer, where the cancer is diagnosed after it has spread beyond its originating area; the survival rate of indigenous people is also lower because of the predominance of cancers like lung cancer that have a higher mortality rate.

It also differs geographically: prostate cancer is the most common cancer in NSW; pancreatic cancer in Victoria (and second highest in NSW); melanoma, unsurprisingly, in Queensland; non-Hodgkin lymphoma in South Australia; colorectal cancer in Tasmania; breast cancer in women in the ACT; and lung and unknown-primary-site cancer in Northern Territory.

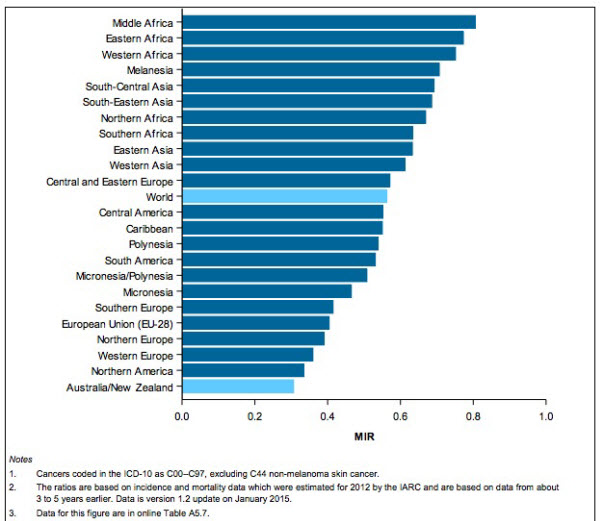

However, whatever criticisms we might make of our health system, Australia is one of the most successful countries for the diagnosis and treatment of cancer in the world. Using a measure called Mortality to Incidence Ratio, Australia (and New Zealand) are the best in the world in terms of of survival; we’re ahead of the US, Canada and western and northern Europe, along with everyone else.

Thank Great Gough for Medibank/care & Big Public Health in the Nanny State, eh BK?

Think about what happens to the 5 year survival figure if your improved diagnostic finds a cancer 12 months earlier, or finds a cancer that was never going to kill you anyway. The statistics are very hard to interpret.

I think you may want to check your data on the most common cancer in Victoria. I doubt it is pancreatic cancer.