In April 1965, a young Oregon student was rushing to attend an anti-war rally. Diane Newell Meyer, then 22, had prepared no placard, so she quickly grabbed an envelope and pinned it to her chest having just scrawled upon it the words, “Make Love, Not War”. The slogan drew attention, as things affixed to young bosoms are wont to, and was reproduced throughout the era of Vietnam War protest on millions of buttons and protest signs, and at least one dreary John Lennon song.

I’m not at all sure this would have sat well with me. The idea of love as an antidote to war is not a sound one. Patriotism, the ardent love of nationhood, is, in fact, effective fuel for combatants and a great pretext for leaders who still speak today about their “empathy” in the prelude to acts of war. Buddhism, the religion of loving compassion, can exempt its most holy practitioners from ethical norms, permitting and promoting extreme violence in the name of love. At our own trivial level, many might attest that those with whom we “make love” are also those with whom we argue most aggressively about whose turn it is to take out the garbage.

Love and war as opposites? I don’t think so, and neither did John Lyly, who saw in 1579 that they could be meaningfully compared. “The rules of fair play do not apply in love and war,” he wrote, and was misquoted throughout the centuries.

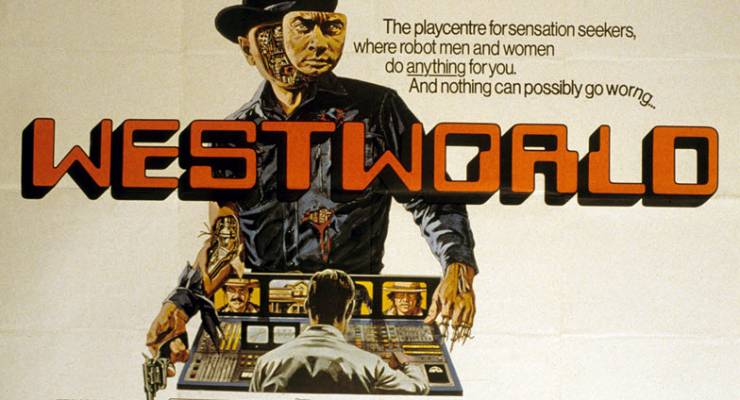

When I gained my first job in the then-emerging internet sector in 1999, another similarity between love and war was evident. By then, it had become very clear that digital innovation had been advanced and funded at speed by both love and war. War is what the world’s most powerful state spends most of its money on. “Love” was then the only digital product consumers spent their money on — do have a look at this primitive “sex robot” from the era, compatible with Windows 95! There would be no internet as we know it without the US military. There would be no system of secure online payments without the famous loving penis of the drummer Tommy Lee.

Of course, we could just accept these gifts of great innovation and say that their bearers — love (or, sex, really) and war — are now out of the picture. It’s not true. Does this even matter? As a (very selective) libertarian, I have no problem whatsoever with the ongoing market power of porn. But, as a (very selective) libertarian, I have great problems with the use of the War Powers Resolution to justify warrantless searches by the NSA of private data.

The rules of fair play will not apply at the NSA, nor should we expect that they will when it comes to sex robots. If you think that the deep state will not monitor your deep penetration of Giggles the FemDroid, well, you haven’t been paying attention.

Martin Luther King Jr. Ralph Nader. Alan Turing. The somewhat less heroic Donald Trump. These are just some of the persons who have been under sex scrutiny by the state. “Love” and war are not only close cousins for those more poetic reasons described in the 16th century. To reveal, or to threaten to reveal, the, ahem, loving peccadilloes of a person for the sake of “national security” is not exactly new. Your sex can be turned to war by the state.

Yesterday, sex robots were again in the news — and, why not, they’re fascinating. Don’t get too excited: Giggles is still years from our embrace. What we can access right now, however, are the conclusions of philosophers who, having lost funding to investigate trifles like the meaning of life, are chattering like Ray Kurzweil on Ritalin about the “ethics” of sex robots.

Goodness, the report is dreary. Like almost anything publicly said about AI and robotics, the answer to the question of sex robots is “it could be good and bad”.

This is the good. There is a strong emphasis in the widely publicised report on how Giggles might help the sexual deviant or the social recluse, and this is a precise and propagandist reflection of how any cyborg-y thing is discussed. When Elon Musk declared his intention to whack neural implants in our heads this year, he led with the announcement that it could help patients of Parkinson’s disease. This is Singularity 101: always talk about how your proposed device will help the disabled! Let’s leave aside that few in government and fewer still in business give a shit about people with a disability. This machine will change all that!

This is the bad. Apparently, Giggles might make some men objectify women. Well, I’d say that horse has bolted.

Whether you like ‘em or not, masturbatory devices have been available for sale or clinical use since the Victorian era. They’re here to stay. While, certainly, the psychological consequences of more human-like wanking tools does deserve discussion, the more urgent matter for mine is: who can see what I am doing to Giggles?

If security agencies can peer inside our refrigerators and remotely operate our TVs as listening devices, then they will certainly take care to learn what part of Giggles I have put into my holes, and how often. It seems curious to me that the Asimovian agencies who talk about our connected future with such hope, or with such timid concern that my gender might be objectified (again, done and dusted, guys) never seem to ask: who will be watching?

We are all aware of the possibility that we are being watched. It is no longer paranoid to think you’re being monitored, but rational. I do not expect a bunch of populist philosophers to ask about the political and military consequences of such surveillance. But, you’d think, wouldn’t you, that they might want to have a chat about how that plays out in the individual psyche?

This new robot love. It will be weaponised. This love will become, as it so often has, a tool of war.

Helen – new phrase to replace ‘make love not war’

HELP! THE PARANOIDS ARE AFTER ME

‘Love and War as opposites? I don’t think so, and neither did John Lyly, who saw in 1579 that they could be meaningfully compared.’

It reminds me about a quote in Robert Sapolsky’s ‘Behave: the Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst’ (strongly recommended – it’s very engrossing once you get past the early very difficult neuroscience, but then everything drops into place, even the ‘rational’ dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) citing Eli Wiesel, Nobel Prize winner and concentration camp survivor: ‘the opposite of love is not hate; its opposite is indifference.’

And you have to hate to go to war.

I don’t care! I’m going to *want* the government to know I have two bespoke sex robots! — one designed to look like Cory Bernardi, the other like Andrew Hastie. Sometimes I join in, and sometimes I just watch …

*applauds”

It has come to pass that I would once reflect upon the paranoid nature of stories like this. Alas, I do miss those times….

Speaking of “those times” – did you look at the Lennon link? Not sure what all the 10yr olds were doing with an aging pop star of their parents’ vintage but other aspects that today would be unimaginable – smoking amidst the kids then grinding out the butt on the park way, the zoo elephant & primate in bare, concrete cells, apart from one slightly rotund bloke nobody was obese and certainly none of the kids, Lennon of course was junkie thin.

Wuz thems rilly the daze?

In defence of Ms Meyer and her hasty scrawl, I would have thought the slogan only works if you DON’T see “love” and “war” as opposites. The primary meaning of “make love” has to be “have sex” – as an alternative use for the energy that might otherwise go into making war. (Tediously beside the point, I know, but that’s pretty much where you’ll find me these days.)

On the main point, if the state insists on surveille-ing me via my apparatus, I very much endorse Owen Richardson’s way of exploiting their curiosity.

Very glad to learn about Ms Meyer. Hadn’t heard that yarn before.