Australian women retire with about half the amount of superannuation as men, and one-third of women will have nothing at all going into retirement, a new study by Per Capita has found. While parenting plays a key role in reducing women’s super, Australian workplaces also remain significantly gender-segregated, with more than 40% of men and a third of women working in industries dominated by their own gender.

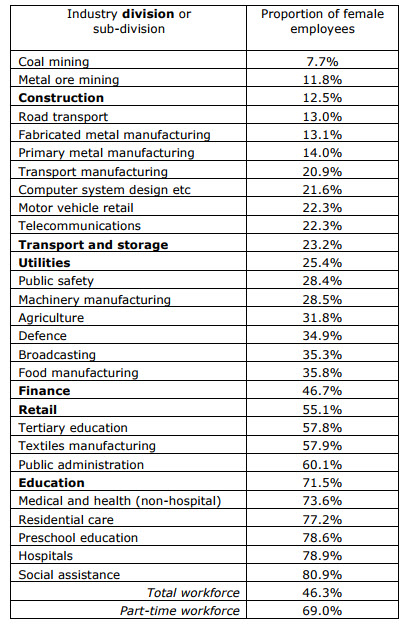

Employment data for the May quarter from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, broken down into industry and sub-industry, shows that a number of industries continue to disproportionately attract men or women.

The most male-dominated industry is mining, where the workforce (which totals around 230,000 people) is around 87% male; in coal mining, less than 8% of workers are female. Construction and road transport are also both around 87% male. Major sections of manufacturing are also heavily male: while the industry overall is around 28% female, metal manufacturing subdivisions are both over 85% male. The only manufacturing sector with a high level of female participation is the small (35,000) textiles sector (58%). The tech sector, plagued by sexism, remains heavily male, at nearly 80%.

Traditionally male-dominated professions like defence and public safety (police, fire brigades, etc) are significantly more integrated: defence is nearly 35% female and public safety 28.4%.

At the other end of the spectrum, Australia’s largest employer, health and social assistance, is strongly female. Social assistance, which means childcare and other social services, is over 80% female; hospitals are nearly 80% female; other medical services around 74%; aged care 77%. Education is also strongly female: overall, the sector is nearly 72% female, although tertiary education, at 58%, less so.

Overall, about 40% of men work in industries where less than 30% of their colleagues are women; about a third of women are in industries where less than 30% of their colleagues are male; and around 40% of women work in industries where less than 40% of the workforce is male.

There’s also been little shift in the gender balance over thirty years in many of these industries and some have gone backwards: in 1987, around 5% of coal mining employees were women; about 26% of the manufacturing workforce; 13.2% of the construction workforce was female and 16% of road transport — both higher than today; in IT, 46% of employees were women, far higher than today. Defence was 29% female and public safety had a greater proportion of women in the ’80s, 33%. Education has become significantly more female — it was 62% female compared to over 70% now. Healthcare and social assistance has grown a little more female — from 74% 30 years ago to 77% now.

And in a sign that construction is continuing to power the economy, the number of people employed in construction reached a new high in the May 2017 quarter, topping 1.1 million for the first time and lifting construction to its highest ever proportion of the workforce, 9.15%. And after several quarters of relatively flat growth, health and social care jumped again to over 1.56 million workers in trend terms, propelling it to a new high of 12.9% of the entire workforce. In contrast, agriculture has racked up its second quarter below 300,000 workers, or just 2.45% of the workforce.

So as our society has modernised and laws have been rightly enacted to ensure unfair discrimination on the basis of gender is made unacceptable and/or illegal, the data shows that industries that traditionally attract men or women have actually attracted them to a greater degree. Or in other words, as societies become more equal, the differences between genders maximise. This seems to disprove the social constructionists’ view that as opportunities for both genders increase, or that as impediments to free choice are removed, we will see the equal distribution of men and women in all facets of society and in every strata of every endeavour.

Am I missing something? In the one Crikey edition (20 July) Alan Austin castigates the Abbot and Turnbull governments for failure to promote the construction industry:-

“Total private and public construction in the March quarter was worth just $46.7 billion. Apart from the September quarter last year — which was an equally dismal $46.5 billion — that was the lowest since March 2011”

In a later segment by Bernard Keane on gender segregation in the workplace, we are told:-

“And in a sign that construction is continuing to power the economy, the number of people employed in construction reached a new high in the May 2017 quarter, topping 1.1 million for the first time and lifting construction to its highest ever proportion of the workforce, 9.15%”

Can I presume from this that construction workers are being paid less and less to do more and more?

Colin Edwards