In a world that seems to be more rather than less prone to confrontation, China and India are now squaring off against each other on a remote plateau in a corner of the almost-as-remote country of Bhutan. Bhutan, an ally of India, is wedged between the two Asian powers, with China claiming a sliver of Bhutan as its own.

The Chinese claim to a part of Bhutan reflects the fact that the border between Bhutan and Tibet, now part of China, was agreed to under historical sufferance. More importantly, however, as China’s economic and military strength has increased, it has extended the assertion of its territorial claims to areas that are, at best, historically contested and, at worst, contravene contemporary international law.

There has long been a regional theory that when China is weak it contracts, and when it is strong it expands. This characteristic can be traced to ancient times, with the external impositions of the 19th century and the internal chaos of the first half of the 20th century marking another Chinese low point.

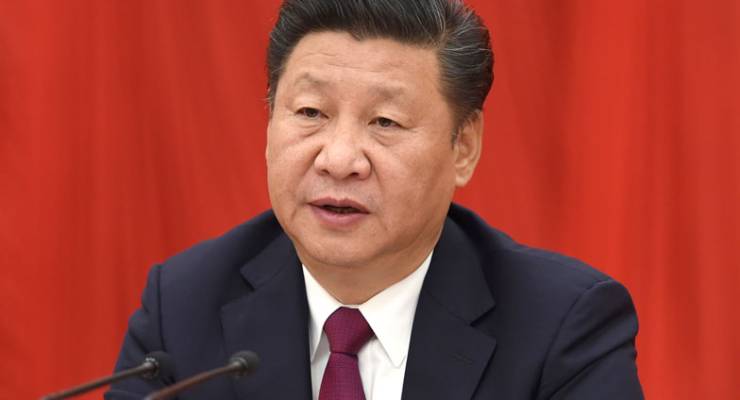

China is, however, increasingly strong again, seeking to expand its influence and, more importantly, its territorial reach. Not content with its claims to the Senkaku/ Diaoyudao Islands in the East China Sea and its less historically sustainable claims in the South China Sea, China is also seeking to redefine its land borders.

There is little or no economic or strategic advantage in pressing land claims, given they are marginal and will likely cost much more than they can deliver. But in terms of asserting its regional authority, China’s move in Bhutan is an act of political confidence, if not bravado. The question is whether it might not also be one of hubris.

India has been quick to respond, sending troops to Doklam, a narrow plateau that lies at the intersection of Bhutan, India and China. As a rising power itself, India is equally keen to show that it is a regional, aspiring world power not to be trifled with.

In Asia’s chess game, China and India have always been the key pieces on the board. Pakistan has sided with China to counter India, as has Sri Lanka after India’s mishandled intervention there to end its Sri Lanka-Tamil Tiger war in 1987. Bangladesh, on the other hand, is friendlier towards India, in part because India delivered Bangladesh independence from Pakistan in 1971 — since tested by Hindu-Muslim tensions — and in part because it is encircled by its vastly larger neighbour.

The showdown on the Doklam Plateau could, in theory, escalate into direct fighting. India and China conducted a brief war in 1962 over disputed border areas. In reality, the border areas between the two countries were always in the remote and undefined frontiers of the respective empires, until the imperial British imposed a border the late 19th century.

The British drew hard boundaries in areas where there had been none, some of which which were subsequently subjects of contention. Bhutan’s border with China was similarly demarcated in 1890, with territory south of the Chumbi Valley being Bhutanese, even though this area had historically been part of the trading region of the Tibetan, and hence Chinese, frontier trading market of Yadong. China and Bhutan agreed to respect the 1890 status quo in 1988 and 1998.

All of this would be a fascinating glimpse into regional history if it were relevant to current events. The reality is, however, disputes over lines on a map are, at best a pretext for nationalist muscle-flexing.

For China, asserting fully all of its sometimes doubtful territorial claims is a matter of national pride. It is also a matter of the Chinese “Communist” Party finding new, more nationalist-oriented ways to legitimise its one-party rule in a decidedly non-communist country.

Similarly, while India is a multi-party democracy, its own brand of nationalism has been steadily rising since independence. India’s current ruling BJP (Indian People’s Party) is an avowedly right-wing nationalist party with alleged parental links to the nationalist militant RSS (National Patriotic Organisation).

An “ex” member of the RSS assassinated India’s independence leader Mahatma Gandhi in 1948 for agreeing to the partition of India and Pakistan. The RSS has since been involved in numerous violent attacks, primarily against Muslims living in India.

Thus poised, a sliver of land more or less belonging to no one but its local inhabitants has become the site of a showdown between two increasingly nationalist regimes. It started when a Chinese road construction project crossed the border to the south.

China now claims this extension of road is in Chinese territory. Continued tussles in this dispute are likely, and blood might even be spilled, as it has been from time to time over India’s disputed border with Pakistan.

The dispute is, however, unlikely to lead to open warfare between the two giant countries. The first reason for this is that both countries are nuclear powers, precisely to establish “credible mutual deterrence” to forestall such a war. China has about 3000 nuclear weapons; India has about 1000 — enough to annihilate each other’s country.

The second reason is that the land in question is, ultimately, worthless, even as a bargaining chip with Bhutan. Tensions may continue, but after a bout of breast-beating and sabre-rattling, both China and India will likely look to a face-saving withdrawal.

As both countries grow, the celebrations are only just starting to get going in each country. Neither wants an ill-considered stoush to end it all prematurely.

*Damien Kingsbury is Deakin University’s Professor of International Politics

“Credible mutual deterrence” is an intelligent concept in the fascinating game of international politics that the author sketches for us. However, “mutual annihilation” is yesteryear’s hyperbole, invoked as if we Crikey readers are too stupid to believe that any war at all is bad news for both countries.

‘any war at all is bad news for both countries’, but not for the arms manufacturers.

This article overlooks a number of key points. The first is that the 1890 Treaty between India and China has been repeatedly accepted by the Indians as valid today.

Secondly, the border that was drawn under the 1890 convention did not include Bhutan.

Thirdly, India has sent troops to Bhutan where it has no legal standing, in order to confront China. What does Mr Kingsbury ignore this crucial point of international law?

Even if the Indian argument is correct that the territory in question is not China’s, that still does not give them locus standi.

To understand the Indian intervention one has to understand the wider issues, including Indian resentment over the BRI and more particularly the CPEC which passes through the Pakistani section of Kashmir.

To describe it as an example of China expanding its borders along with its influence is simply arrant nonsense.

An interesting excursion into an exotic region by our resident Langley VA correspondent – nothing new or even accurate but hey, that’s our Prof.

Which raises the question, why is the Hegemon even bothering to fax this script to its stenographer?