A perennial question for any activist movement is how to get the public on side. In the case of the union movement, much like being a good house guest, it certainly helps if you have beer or ice cream.

The dispute between the Australian Manufacturing Workers’ Union and Unilever regarding the employees of the Streets ice cream factory in Minto in New South Wales is, in numerous ways, similiar to many the union has been involved in recent years.

Unilever, the company that owns Streets, has applied to the Fair Work Commission to have the existing agreement covering the Minto workforce terminated. The FWC has yet to make a determination. If Unilever is successful, employees would have to negotiate a new agreement on the basis of the award conditions, rather than the much more generous provisions of the current agreement.

As Crikey has noted, the practice of employers applying to terminate agreements during negotiations has become increasingly widespread, particularly in manufacturing, with Griffin Coal in the Western Australian mining town of Collie, as well as Aurizon, Esso, AGL, Parmalat using the tactic. The AMWU has tried to rally public support for their campaigns in these areas, with mixed results.

However, the AMWU may be heartened by the fact that the Streets dispute has an important link to one of the most successful campaign’s in recent union memory — a big clear target for boycott action. Across 2016, the union was locked in battle with Carlton and United Breweries over pay cuts for workers at the plant in Abbotsford, Victoria. In the CUB dispute, 55 Abbotsford brewery employees were sacked and offered their jobs back at a 35% pay cut via a revised contract through a labour hire firm, which the workers refused.

What followed was a social media campaign, primarily led by the AMWU and Electrical Trades Union, but publicly backed by the Australian Council of Trade Unions, aimed at getting the public to stop drinking CUB beers during the dispute. It got wide public support, and eventually the workers were reinstated with all the conditions they wanted.

Unilever produces a number of high-profile ice creams at the Minto site, including Magnum, Golden Gaytime, Paddle Pop, Bubble O Bill and Calippo. Professor of marketing at RMIT Francis Farrelly told Crikey this makes the company very vulnerable to strike action.

“Iconic brands are definitely the most exposed to boycotts, because they live in our culture,” he said. “Many successful boycotts utilise what’s called ‘the doppelganger’ — which uses the emotional content, the very essence of the brand and its iconic images against them. So Streets is very vulnerable because their brand is about family, togetherness and kids, and that can be used against them.”

Farrelly described a tweet from the CFMEU reimagining Streets’ famous Golden Gaytime logo as “Stolen Paytime” as “classic textbook number one use of the doppelganger”.

Associate professor Bobbie Oliver, labour historian at Curtin University, said boycotts had long been a tactic of the union movement, but were more likely to be successful when there was one clear, high-profile product to target.

“It has to be something a lot of people can do and are willing to do,”she said. “There are some boycotts which require huge sacrifices — for example the Indian nationalist movement, where Ghandi told people to boycott Western universities and Western forms of dress — and they often have mixed success. But with CUB, say, it just required people to switch brands. And ultimately, that’s what really matters, when it really hurt their bottom line, and that’s why Carlton eventually reneged.”

Oliver compared this with the unsuccessful opposition to pay cuts at Griffin Coal, whose product didn’t allow an easy boycott.

Steve Murphy, incoming secretary of the AMWU NSW, told Crikey Unilever’s concern about its brand would play a part in the campaign.

“Unilever has one of the largest marketing budgets in Australia, and Streets ice creams are heavily advertised — especially in summer. They care about how their products are seen,” he said.

“Consumers expect that their products are made fairly. If Unilever slashes their workers’ pay by 46%, we are going to make sure that people are thinking about that when they walk down the supermarket aisle or visit the local servo.”

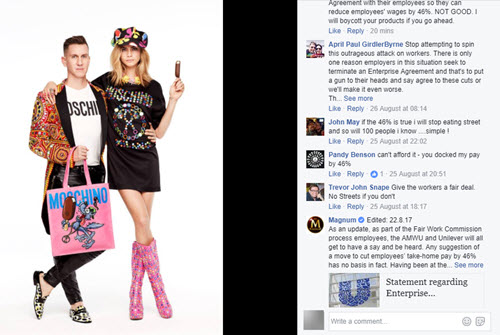

Indeed, Streets have been fending off angry comments from customers on the Facebook pages of various products for example having to slightly undercut the glamour of an announcement about their “collaboration” with actor and model Cara Delevingne by accompanying it with a statement about the FWC process after a series of comments about the dispute. Sample comment: “I hear Streets, the makers of Magnum, is planning on breaking the Enterprise Bargaining Agreement with their employees so they can reduce employees’ wages by 46%. NOT GOOD. I will boycott your products if you go ahead.”

“We understood this matter might attract attention, but our focus is on the need to enhance the competitiveness and viability of the Minto factory going forward, which is ultimately in the best interests of our employees, customers and the company,” a spokesperson for Streets told Crikey.

“We will continue to engage through the Fair Work Commission process where employees, the AMWU and Unilever and will all get a fair chance to have a say and be heard. We will also keep communicating with our customers and consumers to ensure the information they receive is accurate.”

Farrelly said the dispute had real risks for both sides.

“For the union, they risk alienating the public, who might be questioning if they are getting the whole truth with sensationalist claims,” he said. “Plus, ironically, if they are too successful in their campaign to damage the Streets brand, it could have long term implications and make it difficult for the company to employ their members.

“It’s a real risk for Streets too, if they reply with sensationalist claims of their own, and turn it into a protracted ugly public debate — they could do themselves a great deal of damage.”

Streets are playing a dangerous game. No doubt they want to reduce their prices closer to the Aldi look-alikes but if they piss off their currently loyal customers those customers may well discover that competing products are pretty good as well as being much cheaper.

It’s GANDHI!

Honestly Crikey, must you depend on amateur sub-editors like me?

It’s the fourth glitch today – and I haven’t even read some of the articles.

The big one to watch on this front is Murdoch University, who are trying this stunt.