Now. Before you get angry with me for reminding you of recent Australian headlines you’d possibly rather forget, do me this one solid: know that I, like you, do not write the news. We are both cruelly forced to endure it. The power of social media and search engine algorithms ensures we cannot avoid what corporations determine to be the big stories of the day. There is no app or extension to block out the noisy problem, so all we have is solemn cures. Consider this your controlled group therapy.

And now consider a week, and an era, that allows a form of uncontrolled, possibly detrimental, group therapy to dominate news, and many other media.

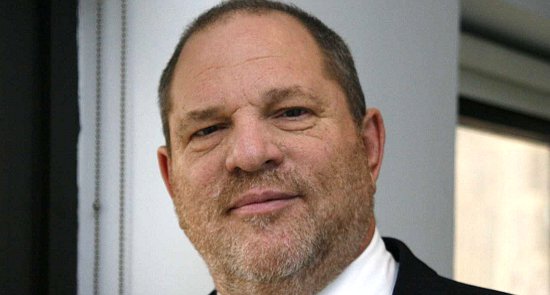

The social media hashtag “#metoo” (or “Me Too” for the reader who retains their fondness for written English) became news when the American actor Alyssa Milano proposed it. Following the multiple allegations of abuse by women, many of them well known, against US film producer Harvey Weinstein, Milano responded. She urged all women, even those who were not famous, to describe their experiences of sexual abuse.

[Instagram it. Hashtag it. Save the world.]

We might admire the democratic intention here; Milano was attempting to show that the problem of abuse extended beyond five-star hotel rooms in Beverly Hills. But, what we might be critical of is her invitation to women (not men) to publicly disclose their memories of harassment or assault. What we can certainly be critical of is the decision of news-makers to buoy this plea.

Call me old-fashioned, but I do not consider Facebook to be the most dependable therapist. Certainly, there are those few women able to speak publicly, even professionally, about their private trauma. Then again, even among the media class, or aspiring members of it, there are women who have suffered keenly when they disclosed one harrowing story of abuse, then became immediately useless to the publisher for any other sort of work.

This is how #metoo may appear to the victim still processing her trauma: Gwyneth and Alyssa and Clementine are applauded for their public disclosure. Public disclosure is immediate therapy. I will do as they suggest, and find catharsis by publicly reliving the moment of my pain.

It is possible, of course, that there are those women who will benefit from acknowledging their hurt; of being, perhaps for the first time, believed. It is inevitable not only that some women will find their troll antagonists, but that plenty of them will be dumped over time by what now seems like a gentle tide of acceptance.

This is not to say that “silence” is a preferable strategy. This is not to “silence” women, or anyone, which you can’t do effectively with social media, anyhow. It is to point out to you, and to snarl at my colleagues, that the purpose of journalism is alleged to be public interest. There are guidelines for reporting on suicide. There are proposed guidelines for reporting on domestic terror incidents. Use your noggins and acknowledge that a trauma like rape is not only to be reported by you with great caution, you have absolutely no business urging others to self-report.

[Razer: how mainstream media became a clearing house for simplistic opinions]

Of course, this, as Guy Rundle points out, is how we do “politics” these days. We don’t have organised mass movements that may actually address a serious matter like sexual violence or workplace harassment. We more often opt, even within organisations, for a great surge of individual stories that serve to inspire, “raise awareness”, or, as Milano suggested in her initial tweet, “show the magnitude of the problem”.

What we do not show in such political movements is our own magnitude. We are a mass. If we want something, we demand it. We do not seek to persuade by baring our most intimate hurt.

We do not believe in political action so much as we believe in the political power of painful stories. Some felt sure that story of Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi would end the Syrian war. Even president Barack Obama — at the time, the individual most empowered to end that war — mentioned that story’s power. Obama was moved, but not to act. The proxy war continues, and somehow our faith in the healing power of stories does, too.

Stories do not always heal. Stories can often hurt. Especially when appropriated by unthinking, click-ravenous media machines.

Surely we have to get beyond the binary of ‘tell your story’ or ‘silence’ and beyond the notion that any particular media act can ‘change everything’? I suspect that the use of the me too hash tag was an attempt to illustrate numbers and perhaps, in that way, many silent women were comforted that they weren’t alone. I suspect that some of the shared stories were salivated over by somewhat sleazy men, writers can’t control what readers think (to add a simple note of high theory).

I also noticed that my generation, older but used to the issues, just used the hashtag and left off the story. Some added to the comments an expression of relief that they/we had reached an age that was no longer so continuously ogled, touched, talked over at work, etc.

But really it isn’t about women telling their stories, but about those who discount such stories, whether man or female, learning to listen and begin to understand the flood of stories as evidence of power relations, not individual relations. Yes, I know that you know this – just thought it was better said in this flood of personal pain.

In these disgendered modern times, would it not be more to the point to acknowledge that abuse in all forms, personal, sexual, commercial, political, environmental etc arises from the nature of power.

What do strong leaders need above all else? FOLLOWERS, people too inadequate to make their own way in the world and thus, remora-like, attached to the big beasts.

We are not, most of us, Homo Sapiens so much as Homo Obedius, willing & eager to do what we are told, when we are told and to whomever the Boss fingers.

To stand against that paradigm would mean thinking for oneself, hard enough, but then being responsible for the results of such independent actions.

Evidence suggests that for about the last 5-10,000 that gene has been fading.

I’m still puzzled as how writing the two words “me too” is in anyway publically disclosing memories of trauma? Just two words – no details necessary.

Wasn’t the point to show the magnitude of the problem with a hashtag? Rather than a focus on sharing personal traumatic stories. The problem around Harvey Weinstein is that people were too afraid or disepowered to talk openly. There was a destructive mysogynistic culture in place supporting it.

I address this directly in the article, Lee.