So, in the end, we were, in fact, to blame … It is always the stronger one who is to blame.

— Dag Hammarskold, Markka

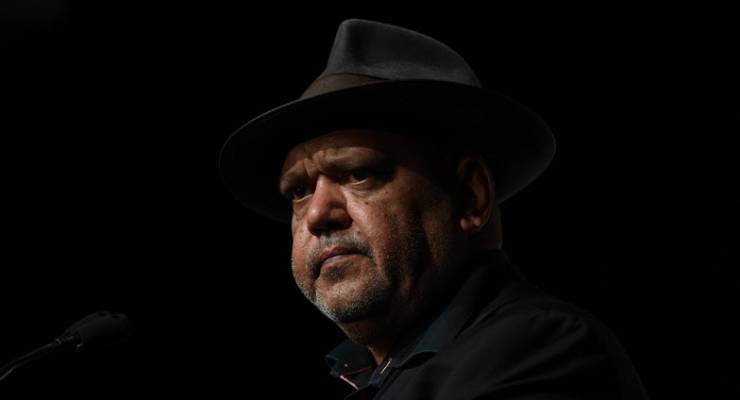

Nothing illustrates the paradox of Noel Pearson better than his latest appearance, a long essay in The Monthly entitled “Betrayal“. This is among other things, a purported confession of “seventeen years of failure” in trying to put together some sort of grand fusion of Indigenous social politics (with the advancing of things like “direct-instruction” education) with a constitutional politics that would advance recognition and structural change in the Australian state. The “betrayal” is Turnbull’s curt refusal to take the Uluru package — recognition/treaty/advisory body — to a referendum, allegedly reneging on a commitment made before he became PM.

It’s pretty excoriating, and self-excoriating in its own way. Pearson does portray himself as having been something of a fool, wasted vast time and energy, made many mistakes. The prose is often awful — “The day after Turnbull’s betrayal, my friend, the doyen of The Australian, Paul Kelly, came down from his mountain at Holt Street with those heavy tablets of stone …” — but it will be celebrated as genius. The Pearson paradox will kick in: denouncing himself as having got it all wrong, he’ll be feted all the more by his devoted supporters.

Pearson’s approach to Indigenous advancement and liberation deserves a longer treatment, but the gist is this: from the mid ’90s onwards, he attacked any and all politics of symbolism, the left for promoting victimhood, and advocated a strong focus on “taking responsibility” through full-time work, highly structured education approaches, and so on. He advocated a mixed modern-traditional society; but it sounded as if this child of a Lutheran mission believed that complex remote societies would become little Frankfurts-on-Cape-York, with trad culture in the arvo, and that kids would love the dour, industrial direct-instruction education system.

“Betrayal” suggests that recognition, treaty and a first peoples body were Pearson’s intentions all along. Well good to know that now. Because at the time it seemed that after 10 years of undermining cultural and symbolic politics, he was turning around and diving deep into it. Suddenly, he was out the front of it, with a big “R” on his T-shirt, leading the charge for a big recognition deal, that Turnbull agreed to, then welched on. By then, top-end Bavarianisation had not occurred, and the most visible result of direct instruction was three kids so pissed off with it, they carjacked their principal with a machete (shows initiative and project management skills). Then the big recognition deal disappeared. The political survival calculus of a prime minister leading a coalition of a liberal propertarian party and a rural white party trumped his earlier effusiveness. Betrayal? More like “fool me twice …”

So what went wrong in this dual failure? Well, everything really. Pearson was picked up too quickly, by two sets of people: white left-liberals, who wanted an MLK figure, and the right, who duchessed him. Pearson had some political skills, lacked others: a resistance to the flattery of power, a degree of cool scepticism. He lacked knowledge in key areas: a genuine grounding in social theory and critical anthropology, which would have produced a different strategy. His arrogance went well beyond youth: “I am full of regrets … About the mistakes I made. Litanies of them. They can’t all be offset against other people’s mistakes … ”

Goodo, but there were people, black and white, pointing out these mistakes, in real time, for years and years, and with two clear and simple arguments: Indigenous societies are not modern, Western societies in embryo, waiting to follow the same trajectory; and movements cannot be built, are in fact demobilised, by endless lobbying for the big deal. Both are arguments from the left intellectual traditions he rejected, or simply did not know well enough. Trouble is, the essay suggests he still hasn’t understood that superficial formulae lead to these results:

“The radical centre is still the place to hunt. What I have learned is that only those with power can take the country to the radical centre. Activists on the outside can advocate for the brilliant centre but only those who command the structures of power can cause the tectonic shifts.

“My critique of progressive thinking still holds. The leftist confusion of ends and means still remains. We share the end of social justice, but the means by which that justice is secured is still the subject of dispute.”

That’s drivel, Noel. It’s just plenary session-powerpoint-Qantas-lounge-free-popcorn-drivel that you use to cover the gaps in your knowledge and analysis. Stop doing it.

The same goes for his enablers/admirers. They needed in one young man a figure who would assuage the guilt of living in a white settler society, where the killing never stopped. Will they now recognise that the essay’s title is turned partly towards them? Or will its admirable rawness be aestheticised, its lessons unlearnt, other voices unsought out of a remnant moral vanity? Pearson’s enablers are, after all, the stronger ones, and that, above all, would count as a failure of recognition.

excellent, my thoughts exactly

Thank you Guy.

The commodification of disadvantage wit large in the utter failure to Close the Gap in Indigenous disadvantage is at the heart of Pearson’s elevation.

OK Guy Rundle, enough’s enough. I’ve read you, laughed with you, approved of your excoriation of the appalling idiots in the corridors of power. But now, you’ve gone too far.

You’ve kicked a great man when he’s down. By his own admission, Noel Pearson spent 17 years backing the wrong horses. He took a calculated risk, was vilified from the left and now it would appear patronised from the right, by those he thought he could trust to do the right thing when the time came.

And they pissed in him. On receiving the gentle request of The Uluru Statement From The Heart, the request for a Voice in how they were to be treated by the whitefella’s parliament, what was the response?

The Indigenous Affairs Minister, Nigel Scullion, said that this Voice, central to the Referendum Council’s submission to Parliament, an external body to advise on legislation affecting Indigenous Australians, was “neither desirable or capable of winning acceptance in a referendum.” Neither desirable or capable.

And the prime minister’s response? “This is not what was asked for or expected.” In that essay in The Monthly, Noel Pearson writes that Turnbull ‘appears incapable of understanding that he simply cannot say such words. He established an independent council to provide a report making recommendations for constitutional reform, then he complains that this was not what he expected or asked for?’

So where was your criticism of these gutless bastards (and where was Shorten when this happened, this, yes this betrayal?)

So, Guy, who have you been fighting for for 17 years? Were you fighting for your people who were being thrown in gaol, dying in custody, taken away from the families, drowning in alcohol and drugs on neglected remote communities? No, oh, sorry, I forgot, your people are the ones who are the lucky recipients of white advantage. Through no effort on their part. Just the lottery of pigment.

There were so many ways you could have responded to Pearson’s self-admitted failure. You chose scorn. You chose to sneer, to kick him, to pick over the scabs of past wounds.

Shame on you. Shame on you using your considerable skills in this way.

Noel Pearson will be remembered as a great fighter for his people. How will you be remembered?

Yeah Guy, where is YOUR giant trail of failures stretching across decades?

Demonstrate one — just one — remote Indigenous school program that is as integrated, comprehensive, rational with demonstrated, independently established positive academic outcomes as Pearson’s? I include decades of state education in this challenge. I’m waiting.

I’m impressed. Could you give a reference?

Or provide a link, as the kiddies sez.

AR, I’m sorry, i don’t understnad. A link to what?”

Richard, I can;t do that, and it has nothing to do with Rundle’s story or the Pearson story that prompted it. Pearson was speaking only about one particular betrayal, the last in a series over 230 years that has led us to the present day.

I’m not qualified to comment on education, maybe someobdy here is.

John – a link to your assertion of spiffing results in the skool syllabus – amerikan tick box (and wildly culturally inappropriate one might have thought) roneod sheets.

John

That’s exactly the sort of self-defeating idolatry I’m talking about. As I said, plenty of people, plenty of them indigenous, were making the criticisms of Pearson’s strategy that he now makes himself. They were in the same struggle – simply less celebrated. Pearson’s essay itself is an invitation to better analysis – not to use him as a figure for liberal white emotional needs.

Idolatry? Hardly Guy. Just yesterday I was talking with blackfella friend about Pearson. He didn’t always agree with him, but the standout for him and me was the way in which the Voice was dismissed by these two self serving …I’m looking for a word, let’s just say politicians, that’s enough of an insult.

I know Pearson was not the most popular man among some in the Indigenous leadership, and I know there was grumbling about The Statement From The Heart. But let’s go back to Turnbull’s dismissal of it: “This is not what was asked for or expected.”

Politics and personalities aside, that was a totally unacceptable response from a totally unacceptable human being.

John,

I understood Rundle’s essay to be a critique of Pearson’s The Monthly essay – so went there to look at what Pearson actually wrote. Aside from the quotes used in Guy’s essay and in others’ comments here, I found this one from Pearson curious:

“When faced with the question of whether we predicate our struggle on the political right finding compassion or the political left finding its brains – I now know the answer. The left have an altruism the right will never muster. Every progress we make will have to be fought for, and every battle will be partisan. Bipartisanship is dead.”

Pearson is, or was until he realised the pointlessness of his quest, on a mission to find compassion and altruism in an Australian body politic when all that is on offer is pragmatism Keating-style. The question is, could the Uluru “package” have been delivered by a better storyteller, one seeking neither “brains”, compassion or altruism (an elitist approach if ever there was one) but instead putting a proposition directly to the Australian public. We know it wasn’t a third house of parliament being proposed so why talk to those inside the tent about what might happen in the space outside the tent? Why not take a mandate from fellow Australians TO the parliament rather than trying to cut a quickie deal with a couple of cabinet members there? Sadly, it looks like if Pearson couldn’t get there, no one can. Rundle argues that Pearson wasn’t up to the task. Pearson appears to agree with him.

Once again, the point is being missed. Pearson was not the deliverer, but only one of the team who wrote the Statement.

And none of the correspondents here seem to give a stuff about the arrogant dismissal of the request with no request for a way forward. It has hardly been mentioned since. We’ve been too busy deciding who is Australian to bother with the only group in the country who don’t need to prove their right to citizenship. We whitefellas are all from somewhere else.

I am disappointed in the Crikey readership, all too willing to put the boot into Pearson (and as you note Hugh he does that himself) but not into the snivelling gutless white supremacists who run this country .

John, you wrote (below – there’s something odd with the ‘reply’ format) that Pearson was “not the deliverer”. Yet in the “Betrayal” article Pearson wrote:

“On Thursday morning I sent a text to Turnbull: “PM, I’ve seen the Courier-Mail report on cabinet’s rejection of the Referendum Council’s recommendation. Would be good if we could talk soon as.”

I received no response.”

It’s pretty clear that Pearson was the ‘deliverer’ and he wasn’t getting anywhere. He found, as so many others have found with our legless PM, that if the path is not freshly brushed clean and clear, Turnbull won’t be going there, regardless what what was said or promised years, weeks or even minutes ago.

Charlie re delivery, from the Antar website:

On the morning of 14 February 2017, Jackie Huggins Co-Chair of National Congress for Australia’s First Peoples handed Prime Minister Turnbull a Coolamon holding the Redfern Statement. In doing so, on behalf of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, she called for:

“A new relationship that respects and harnesses [our] expertise, and recognises our right to be involved in decisions being made about us”.

She appealed to the government to: “Draw on our collective expertise, our deep understanding of our communities, and lifetimes of experience working with our people.”

She made clear to the Prime Minister that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have the solutions and that it’s time Australian governments listen and genuinely engage with Australia’s First People.

OK, I’m not so concerned about the technicality of who actually handed over the document. The fact appears to be that Pearson saw his own role as guiding the document through the process. He was the facilitator, the one that had received the nod from Turnbull (two years before) and felt that he had the ear of the PM. Pearson didn’t stand back and let others do the negotiating, no, he took to the phone himself – although there was no one on the other end of the line.

And that, Charlie, going back to Rundle’s story, is what he missed.

Hmm, ‘human being’? I tend to think of him as Gore Vidal described Al Gore (a distant relative), ‘a human shaped object’.

This was re JohnNewton’s last sentence on Dec 6th, at 3.15pm.

{{I’m curious as to the tekky reason some replies to replies sometimes omit the REPLY option.}}

ooohh, just like mine above. Must be a numbers thang.

when noel pearson hopped into bed with howard and the coalition, he sold his soul to the devil, when you share a bed with howard you get kicked out when your usefulness runs out, just ask meg lees, so now pearson is scorned by the libs and not trusted by labor, pauline hanson will be the next LNP bedfellow to suffer the boot, her usefulness expired in queensland when she took votes from the LNP and not labor so its only a matter of time till she joins pearson in la a land, where the the not needed, not wanted and not trusted always finish up., they should study the political history of the australian democrats, its too late for them but its a lesson others should learn.

One Notion actually took Labor votes.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-05-20/election-2019-towns-that-turned-on-labor/11128384