The corrosion of truth in these strange times is terrifying.

–Richard Flanagan, The Guardian, March 20, 2017

Richard Flanagan sets a very high moral bar for us all, so when I read he was writing a book about the time we worked together on the autobiography of a now forgotten fraud, I was interested to see how this would relate to the high-minded arguments he made in that Guardian article. Like …

“What if truth is the precarious hinge that holds freedom and progress together?”

And:

“Lies have become alternative facts and truth irrelevant in the face of power, while we all give up our privacy.”

With that powerful promise, I looked forward to reading the book and was caught a bit off guard when I found myself fictionalised in Flanagan’s new book, First Person. Coming from behind the author and onto the page isn’t a very comfortable position for a publisher.

Trouble became clear fairly quickly. The author says it’s fiction, but he was relentlessly out promoting the book as drawing on his very real life experience. When does the reader know he is being a novelist or retelling the actual facts? It wasn’t reassuring when I read a review that suggested it is all basically factual “with only the names changed to protect the guilty”. Should I worry when he says “fiction is not a lie but a necessary truth”?

The vapid, venal figure he depicts as his publisher in 1991 may be the result of his interest in satirising publishing in general, or it may be because that is what he thinks of me. Either way another review suggested the book was “a devastating satire on the world of publishing”.

Should I be devastated? I was when he described Gene Paley (the publisher in the novel) as having flabby upper arms. Because that gratuitous description followed a series of conversations, meetings and agreements that I remember well.

Paley is scared of literature, all about the money, loves mediocrity and is in the thrall of a very Bryce Courtenay like character (I was Bryce’s publisher at the time).

With Flanagan controlling the fictional dialogue, he was able to enhance his own role by adding touches that don’t accord with my memory, or that of Louise Adler, my colleague and his publisher on the book inspired the events in First Person — but they sure are helpful creating that devastating satire of a hapless, greedy publishing house.

All necessary truths?

I remember reading The Narrow Road to the Deep North and feeling sorry for Weary Dunlop, the apparent basis of the central figure, who was revered for his work in the war, but depicted by Flanagan as an overrated lothario. At least Flanagan didn’t fictionalise Paley’s sex life.

And the more I sat feeling “devastated” by my depiction, the more it occurred to me that whilst I had become a cartoon character, Richard’s own persona in the novel had grown into an authentic working-class hero, not the recently minted Rhodes Scholar from Oxford University I interviewed and then contracted in 1991.

Truth and satire, facts, lies and even omissions — it’s hard being a fictionalised character.

I now have more empathy with all those people who tell me they have been depicted as a character in a Helen Garner novel.

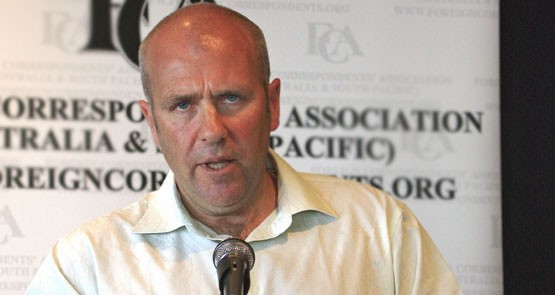

*Sandy Grant is a book publisher and co-founder of Hardie Grant.

I read Narrow Road to the Deep North because of certain relatives and their fate. My birthday is also the anniversary of my uncle’s captivity by the Japanese in Singapore. I found it a moving, dark, difficult and compelling read. I am well versed in military history and the Dunlop legend. I never saw Dorrigo as a Weary Dunlop figure, Dunlop after all was a great and extraordinary man, but not the only brave one on the camps or the only medical officer who went beyond the call. Rather. I saw a conflict between the public and private man, and we all know one. Someone who will face anything, but is a philanderer, or a gambler. Good is not necessarily absolute, though it can be. Neither is bad. I have yet not read First Person, though I found the concept interesting. I have heard Flanagan speak about it a number of times. Were I to read it, I would not know who the “publisher” is. Flanagan, when I have heard him, has not done more than outline the rather unusual circumstances behind the original event. Once again, do we know what Bryce Courtenay was like well enough to make the link? Flanagan would be wrong to make too close a suggestion in reference to you, but is it you or an amalgam which includes you?

Maybe it would have helped if Flanagan had fictionalised Paley’s sex life. Then you would have known for sure that it wasn’t really about you. I read the Narrow Road . . and had no trouble seeing the narrative vehicle. Even though I knew there was a Weary Dunlop figure in the story and some of the wartime actions of that figure may have been similar to the real Dunlop’s, it never occurred to me that the ‘lothario’ was anything to do with Dunlop. I think Flanagan has so many human traits to deal with and serve up that he has to jam a few into every character. Surely there’s something about Paley (who I haven’t met yet) that is totally not you?

I remember the news story on which RF’s latest is based. It’s recently been serialised on BBC Radio4. I listened for a while, then it got too dark for me.

DEAR CRIKEY

the bewilderment and annoyance Sandy Grant finds in reading what I gather is a dull, unsubtle caricature of himself in Richard Flanagan’s ‘First Person’ is at once comic yet distressing, for the exercise sounds mightily malevolent. And yet, since well before Old Man Dickens was portrayed as Mr. Micawber (maybe the hallmark of all such in English language literature) writers have been ‘raiding’ ‘reality’ for characters, incidents and plot. Though with this rider: if without the ‘persons’ the ‘characters’ wouldn’t exist, still the final work is very much one of the imagination, of fiction.

For example, in ‘These Things Are Real’, my latest book, I have five verse narratives all of which have people and events based on what I have seen or heard or heard about or read about. Yet the end product is in no way non-fiction or memoire.

And then there must be those times when a writer’s friends are disappointed they weren’t portrayed, or other occasions in which an author stepping back from a completed (maybe long completed) work, can find themselves announcing ‘My god! I actually wrote about him! about her!’

So yes, it is all part of a game and sometimes that game, as in the one under discussion, is very badly played. But ever since John Wren took on Frank Hardy and lost, a libel action from Sandy Grant would be laughable and he can hardly expect Flanagan to apologize. Yet as a publisher he does possess certain advantages and thus should commission a solid piece of fiction in which the protagonist (maybe even the narrator) is a self-promoting, multi-prizewinning novelist, attached to a Group of Eight University, with vapid opinions on just about the lot. I’m sure plenty of writers would line up for the task.

REGARDS

ALAN WEARNE