While jobs growth has been a success story for the Turnbull government over the last two years, a closer look at employment data suggests its economic policies deserve little credit. Instead, growth has been driven by social services spending and the Reserve Bank’s ultra-low interest rates.

According to ABS data, between November 2015 and November 2017, employment grew by nearly 520,000 in trend terms, or around 4.3% — noticeably faster than growth under the Abbott government, which managed only 3.8% growth between November 2013 and November 2015 (Abbott and Joe Hockey were replaced in September 2015). The strong growth under Turnbull and his Treasurer Scott Morrison has driven unemployment down to 5.4% (again in trend terms; all figures here are trend), its lowest level since early 2013.

But while the government has been justifiably eager to boast of getting unemployment back down to the levels of the Gillard-Swan mining boom years, the composition of that growth suggests the idea of a private-sector jobs market powering along isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

In the 12 months to November 2017, the health and social care sector alone provided more than 124,000 of the 395,000 jobs created in Australia — nearly a third. That came after the sector had a brief pause in its long trajectory of growth stretching back decades — in 2016, employment in health and social care barely shifted at all across the year, before surging again in 2017. Meantime, education provided a further 50,000+ jobs in the 12 months to November, on top of around 36,000 in 2016.

As a result, health and education provided just under 45% of all new jobs in net terms in the 12 months to November, and 42% of the 517,000 net jobs created over the two years to November.

In comparison, the private sector struggled to compete as a source of growth. One of the powerhouses of employment in Australia, construction, provided 91,500 jobs in 2017 as the east coast urban building boom — fueled by the Reserve Bank’s record low interest rates — and state government infrastructure projects ramped up. But that followed a weaker 2016 for the sector, so that over the two years, construction provided 23% of net new jobs. The other strong sector was accommodation and food services, illustrating that Australia’s love affair with cafes and restaurants continued unabated: that provided 75,000 jobs over the two years to November, or about 14%.

Manufacturing, however, contracted last year despite the new protectionism that dominates on all sides in Canberra — that sector lost over 40,000 jobs in 2017, almost wiping out all the growth that occurred in 2016. Mining, never a big employer despite the incessant lies of the Minerals Council, shrank 7000 in 2017. Professional services — which in the Labor years was one of the fastest growing sectors — was almost flat over the period 2015-17. But retail, after a very weak 2016, put on 60,000 jobs in the year to November, despite poor consumer spending.

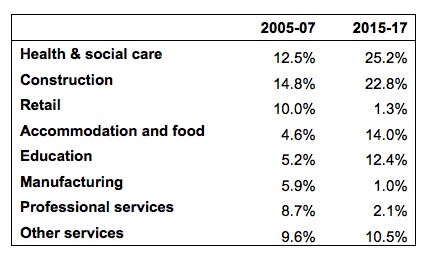

To give some historical context, compare the mix of growth in the period 2015-17 to growth in the last years of the Howard government, when unemployment dropped to around 4%. These are the biggest sources of jobs growth from the two periods:

The government can still claim credit for part of this jobs growth: the surge in education employment has come in pre-school, childcare and school education — all areas where government funding has played a role and the government has increased funding. Responsibility for the big rise in health jobs is shared with the states though, because much of it has come in hospitals rather than primary or private healthcare, and both state and federal governments provide funding for the acute care system.

The Turnbull government isn’t the first to have jobs growth dominated by health and education. In 2009, as the financial crisis hit the economy, they provided 175% of jobs growth — that is, without them, employment would have shrunk in net terms. And in 2015, almost half of all jobs growth came from the sectors. But ideally we’d return to the mix of 2005-07, when government-dominated sectors played a limited role and the bulk of jobs growth came from the private sector. On that score, we went backwards in 2017.

I am not sure how we trumpet jobs growth with a job defined as an hour. Crikey often points out the hours worked per person per month as being very low. I no longer trust the ABS other than on trends.

“The strong jobs growth under Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison ….”

Pardon?

As of November 2017:

*Official unemployment rate is virtually identical to that of 2013

*Underemployment is the highest its been for 30 plus years

*Un and under employment combined higher than in 2013.

actually with nation liquiditating Programs like the NDIS [thought bubble of Gillard to gain electoral traction] unemployment will statistically fall. Where disabled applicant is awarded funds to send them, carer, family on interstate holidays [travel,accomodation,entrance fees to venues] all paid out of the public purse naturally unemployment statistics will look rosey. Health administrators [not front line clinical personnel] are burgeoning . Tick and flick jobs working for accreditation agencies, health and safety companies, pseudo education courses in telephone answering etc are booming . Must not forget certificate 4 courses in courses in cleaning [includes sweeping & mopping]. These are driving the statistics

If statistics are valid analysed employment is falling in the real productive segments of society – every day stores are closing , manufacturers are calling in administrators.

If you look at next article in to-day’s Crickey a town in California seems to have created more real jobs than any State or Commonwealth Government in Australia.

I don’t have a cynical view of NDIS as I view it as a necessary addition to social support, but I believe that it is a big contributor to health job increases. This govt seems to be withholding or delaying funding for this indicative, so cannot be congratulated for this particular job growth to my mind, only being done under duress.

Probably the realisation is dawning that the country cannot afford it. We seem to be wanting to build Rolls-Royce type social support systems with a productivity that can only support motor bikes . The awful realisation is only now beginning to dawn generally on the politicians advisers and the there is no way of extricating the country without hurting the people whose hopes have been raised – Look at Gonski, NBN, NDIS and the list goes on.

We cannot afford it ? What do we lack ? Workers ? Facilities ? Equipment ?

What we need is more tax cuts (less gov; revenue) – that’ll make more jobs ….. won’t it?

You just have to believe in BCA economics and their Limited News Party puppets – and forget about all other evidence? …. That and that Liberal is the god of good news : while Labor is the god of torment (ref. The Book of Murdoch) …. now bring the goat Tosser.

generally low taxed nations leave more circulating money for their citizens to spend creating new ventures -and more productive use of the money .

The evidence – are Hong Kong , Singapore, Switzerland basket economic societies??

The evidence – are Hong Kong , Singapore, Switzerland basket economic societies??

So you’re saying Norway, Sweden, Germany, Post-WW2 USA (before the neoliberals took over), these are/were “basket economic societies” ?

Money circulates when people have high disposable incomes and a propensity to spend. This comes from a relatively wealthy low- and middle-classes.

Money and wealth bubble up, they do not trickle down. That is why we have progressive tax systems. Want to use tax reform to put more money in the places it needs to be ? Raise the tax-free threshold.

…wow. Just, WOW!

Nobody believes this paleocon B/S so we must assume that you are being disingenuous if dumb or utterly mendacious.

Our size and population/density in comparison – fend-for-yourself tax cuts are going to provide the services and infrastructure we need?

The education spend is largely just governments reacting to a mini baby boom in the country over the preceding decade. Guess what, those babies become little kids that need to go to school.

I can’t agree that we can’t afford the NDIS. What we can’t afford is tax cuts to very high wealth individuals and big corporates. We will get nothing back from those tax cuts, that money just ends up in Cayman Islands accounts.

The NDIS work being created was largely formerly done for nothing by carers whose work wasn’t paid and therefore not counted. They need the break, and many will go and work somewhere with the relief they get from their burden, and in the process pay some taxes.

We can’t afford not to have the NDIS.