In the endless election cycle that Australian politics has become, Malcolm Turnbull is facing a greater threat to his legacy than the citizenship ruckus, Tony Abbott white-anting, and Labor’s party polling strength combined: the global economy.

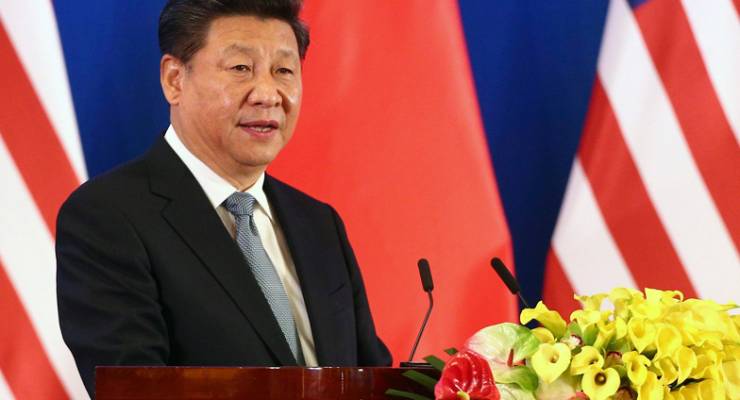

The threats are largely from Australia’ greatest “friends” — trade paramour China, and joined at the hip strategic bedfellow the United States — and therefore unmanageable from Canberra. After five years in power, China’s Xi Jinping finally has the internal clout to enact reforms on China’s bloated industrial sector and to open up its financial sector as rising debt threatens to tip the economy into possible decades of stagnation.

This is both good and bad news for Australia. In the long term, China’s continuing economic heath is essential for the Australian and global economies; in the short term, the country will continue to try and deleverage corporate debt — specifically the steel-making industry, where Australia’s iron ore, its number one export, heads — as well as reducing its dependency on coal, Australia’s number two export.

The expected fall in commodities prices will be exacerbated by Trump’s proposed tariffs on steel and aluminium imports, which is aimed at halting China’s serial dumping of excess capacity, further fast-tracking the shut down of its steel-making capacity. At the same time, falling student visa numbers among Chinese students, highlighted by Crikey, will hit Australia’s major international education industry.

[Are declining Chinese student numbers a casualty of diplomacy or just poor branding?]

The prospect of a larger trade war — the Trump administration expected to announce more measures against China — has already hit global markets, lowering corporate values and therefore the incentive and ability to make capital investments.

The only good news, that the resultant lower Australian dollar means the agricultural sector which will gain in competitiveness for a growing list of Asian customers, is still a piss in the ocean compared to the decline of resources and the education sector.

What China does next will mean much for Australia. In a paper for the Foreign Policy Research Institute, long-time China watcher Professor June Teuful Dreyer, notes that China needs to move quickly to avoid conditions that will make the “inevitable collapse” of its debt more severe: “Worrisomely high levels of debt continue to exist, both at local and central levels, much of it due to earlier stimulus measures. China’s debt-to-GDP ratio is estimated to be an unacceptably high 260%,” she says.

China has already made moves to rein-in spree-happy companies. In February, the government seized Anbang Insurance Group, whose prior purchasing splurge had included acquiring New York’s iconic Waldorf Astoria Hotel. Many other Chinese companies are on shaky ground. Hainan Airlines’ (HNA) regulatory filings revealed that it is billions in debt, one third of which is due in 2018. HNA is currently trying to divest billions of dollars of assets, as is the Dalian Wanda Group. Both HNA — which also has a stake in Virgin Australia — and Dalian Wanda are in the process of shedding major Australian property investments

Canberra’s continued flip-flopping ambivalence to China fits right in with what Teufel Dreyer notes as the concerns of foreign governments and companies about “indebtedness and territorial disputes [being] outweighed by desires to capture some of Beijing’s promised largesse”.

Be prepared for that to come into starker relief as all things China start hitting the economy and next year’s election looms.

The still neglected peasants in China, neglected since 1949, might provide an answer to this problem?

Debts can be paid if the economy continues to expand, and the Chinese economy will continue to expand if that “largesse”, (the massive trade imbalance resulting from artificially low wages, as in Japan before them) was spent on wage rises which allowed the locals, the long neglected peasants, rather than the rest of the world, to consume China’s industrial output.

Wasn’t the US economy built, to a large extent, upon local consumption of its local industrial output, China copies everything else, why not this?

Xi prefers a declension of democracy and sabre rattling instead, to cow the Chinese populace, showing that the deplorables are not all just in the West.

Australians can sort themselves out, they did before after the 1891 depression, without foreign money and its crippling interest payments on debt.

We might need the Commonwealth Bank back again, ( for those struggling with the relevance of the historical method in economics to the above article).

Your point about internal consumption is one studiously ignored in

the mad, bugger… sorry, beggar-thy-neighbour future ahead.

As for a federal bank – oh still, my beating heart.

The US built on Henry Ford’s famous “five dollar” doubling the daily wage and allowing his workers to by the Model T, get out of the overpriced inner city slums, buy cheap housing land, create the American suburbia, with large disposable incomes to fund even more industrialisation?

What’s not to Like President Xi?

And the Australian “Big Four” banking cartel, can it survive the Royal Commission?

A little bit of competition could go a long way?

Some on this list will consider me a nemesis of Mr Sainsbury but it is the case that this article is typical from his kbd and is, as with other articles that I have read, frankly, “all over the sky”. The space required to critique the entire article would occupy about twice the space as the article itself so a few examples, for illustration, will have to do.

“Trump’s proposed tariffs on steel and aluminium imports, which is aimed at halting China’s serial dumping of excess capacity, further fast-tracking the shut down of its steel-making capacity.”

I won’t bother to ask for the basis for this “gem” but it is the case that China intends to control primary industry world wide. That objective DOES affect Australia. In fact, the headline to the article, linked, is “The Trade Issue That Most Divides U.S. and China Isn’t Tariffs “.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/26/business/china-us-trade.html?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=newsletter_axioschina&stream=top-stories

The tariff stuff is an attempt for the USA to have greater access to the Asian market; PRC in particular because Donald really does “believe” that

the country that incurs the trade imbalance (Flexible/Fixed exchange rates aside – which he, clearly, hasn’t considered) is the country that is being ripped off.

Then we’re provided with this insight “China watcher Professor June Teuful Dreyer, notes that China needs to move quickly to avoid conditions that will make the “inevitable collapse” of its debt more severe: “Worrisomely high levels of debt continue to exist, both at local and central levels, much of it due to earlier stimulus measures.”

The reasoning here is not by analysis but by analogy. Indeed there has been a “housing bubble” and a rapid increase in overall debt within the PRC and a country conducted along “Wall St lines” would, ceteris, parabus, have a problem. But the condition of Chinese home-buyers is much less fragile than in the West and moreover, China, takes a very long term of debt. There are any number of business men in China who cannot service the debt but the banks take the longer view (20years+). However even in the USA house debt approached 125% of disposable income on a 5% deposit.

“China’s debt-to-GDP ratio is estimated to be an unacceptably high 260%,” she says.”

I suppose a few other “say so” too but is it the case given the inter-relationships between the financial sector and the (for thensake of a collective noun) government? The matter is NOT a case of “1997-2010 boom” OR a “Japan-style wilderness”. I’m not inclined to write a paper on comparative financial institutions (although I have thought about it. I’ll conclude with a reminder of how the PRC behaved over the Asian Financial event of 1997-8. All? (certainly almost all) Asian countries devalued to ensure some viability of their exports. China did NOT devalue. For the PRC the issue is (and always is) long term and that includes long term stability. Some FDI’s that had an interest in exports to the world from the PRC were hurt (badly) but the long term prevailed. In other words the Chinese “doubled-down” on the bet as I understand a yank might describe the event. Oh — almost forgot : by 2004 China’s export surplus was “exploding” as the world financial press put the matter. It is such perspectives and these that the scribblers for the WSJ (forget Oz) do not comprehend.

I would like to see some “real” analysis undertaken by Crikey. I am able, thankfully, to point to a few (isolated) cases but in general what is written is no more edifying than a front-bar discussion by the intoxicated. The topic selected by Mr Sainsbury is considerably more sophisticated than as, rather amateurishly, presented here.