This week Nauru scrapped a treaty with Australia’s High Court — historically the highest court after Nauru’s Supreme Court — and now has no court of appeal. This is bad news for the Nauruan government’s political opponents, as well the asylum seekers still on the island left without an independent court to hear appeals.

This raises the question: why does Nauru keep making decisions that help the Australian government out? We’ve previously kept tabs on the costs of maintaining the detention centres on Manus and Nauru, and considered why it suits Australia to keep certain countries poor and dependent. In the case of Nauru in particular, that’s only the beginning of it.

Economy

Like so many tiny nations with resources — in this case dense reserves of phosphate — Nauru has been tossed from one colonial power to another. It was annexed by Germany in the late 19th century, then seized by Australia during World War I and finally — after a period under Japanese occupation during World War II — granted independence in 1968. By this time, thanks to colonial exploitation, two thirds of the phosphate was already gone, and Australia, Britain and New Zealand forced Nauru to borrow money against its future earnings from mining so that it could buy out its shares in the mining company jointly owned by the group.

Nevertheless, post-independence Nauru was, for a time, an amazingly well-off country; its phosphate exports made its citizens some of the wealthiest per capita in the world. As those resources were depleted, the government used its mining revenue for a series of devastatingly bad investments, including prime banknotes and Leonardo the Musical (consider that, an economy that can be crippled by investing in a shitty play).

These investments whittled down Nauru’s national trust from over a billion dollars to just over $100 million in only a decade. The exploitation of their one resource left Nauru largely uninhabitable; a fertile ring around now jagged, distended and barren coral peaks, no good for farming or tourism.

This has left Nauru a country that completely relies on other countries to survive. In service of this, it takes some interesting international stances, often, oddly enough, just before or after an influx of money. They recognised the republics of Abkhazia and South Ossetia after Russia scooped them out of Georgia, and promptly received $50 million for their troubles. They got another $130 million from China for ditching their recognition of Taiwan in 2002 and three years later flipped back, and now receives ongoing aid from Taiwan.

In the late 1990s, with the money drying up and the phosphate almost gone, Nauru became a tax haven and a destination for illegal money, reportedly laundering US$70 billion in Russian crime money in the 1998 alone. It was whacked with sanctions for its trouble.

Then, in 2001, the boon of offshore processing presented itself — employment, and a fivefold increase in Australian aid followed. Since the re-establishment of the camps in 2012, Australia is now comfortably Nauru’s biggest source of support, and housing Australia’s unwanted asylum seekers is also a major provider of employment for the island. Nauru’s currency is the Australian dollar.

Health

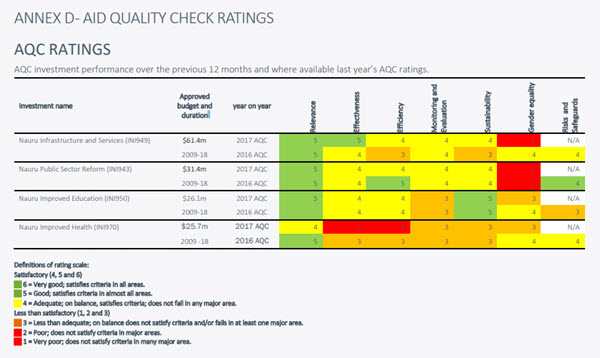

Australia has provided $25.7 million dedicated to improving health in Nauru since 2009. In 2017/18, Australian aid accounts for $3.3 million of Nauru’s health budget.

Infrastructure

In addition to money — of which Australia has provided $61 million since 2009 — Australia can use its greater clout in other ways. In October of last year, the government of Nauru thanked Australia for the role it played in helping Nauru get approval from the United Nations’ Green Climate Fund to upgrade the country’s port.

Education

The Nauru teacher education project is run through the University of New England and is funded by Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, with the Nauruan government and New Zealand Aid. It also has a University of South Pacific campus.

Defence

Australia is responsible for Nauru’s defence. It has no armed forces, only a small civilian-run police force. The agreement with Nauru over their defences is informal.

So, next time you wonder why Nauru so consistently does the Australian government’s bidding — like, say, increasing the cost of a journalist visa to $8000 and then refusing all but applicants who are on board with offshore detention, or remove a court of appeal relied upon by asylum seekers — remember that Nauru simply could not function if Australia decided to shut those funds off.

Excellent yet deeply depressing report, Charlie. Thank you.

Thanks for this factual encapsulation.

Poor buggers, screwed so badly, then screwing up so badly, and now reduced to screwing other people for pay.

A metaphor for free trade?