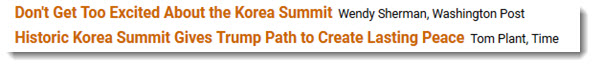

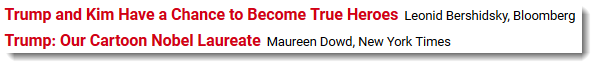

There’s always something amusing about Real Clear Politics at big moments, like a Korea peace summit. The US news aggregator site publishes a daily list of key articles, alternating between right and (by US standards) left. Times like these, it sounds like the Monty Python argument sketch. Thus:

And, from the early morning edition:

Well, OK then, glad there’s common ground on this. What could be worse than a political/culture war of position, using negotiations with an “unauthorised” nuclear nation as pretext?

You don’t have to believe that Donald Trump was pulling late-nighters cramming nuclear inspection protocols to believe that a change in US approach might have played a part in shifting the ground of North-South Korean relations. If it did, it most likely wasn’t Trump doing it: it was the half-dozen or so cabinet and staff who constitute the collective that is currently the President of the US.

But the more likely explanation is contained in Wendy Sherman’s Post article, which makes the point that Kim Jong-un can now afford to negotiate because his country now has a stable working nuclear weapons program. Having developed a system for producing them, they can now produce a sufficient arsenal to later trade down.

The Koreas “deal” is nothing of the sort; it’s just two leaders shaking hands across the DMZ, with the promise of future negotiations. It’s an advance, but it doesn’t bear comparison with the Iran deal negotiated by Obama, which the Trump administration is trying to junk. The truth is that, at the moment, non-specialists don’t have a clue what the real motives, forces and hidden events behind the Koreas rapprochement is.

In the absence of hard information, ludicrous, simplistic arguments, pro- and anti-Trump, are being projected onto the event by all sides. Yet, as this correspondent noted last year, the election of Trump may actually have made the world a little more dangerous — but more importantly, he has made visible the vast danger that would exist without him. That is the combination of national sovereignty and weapons of mass destruction.

Currently, national sovereignty works on a model that is literally mediaeval; at best, we elect parliaments who choose an executive that give a handful of people the legal authority to wage war; at worst, elected god-emperors — the US presidency is an example of that — decide our fate for us. With such a set-up, there is no guarantee that the rational and the irrational can be easily sorted out.

The supposition is that a President Hillary Clinton would not be as rude and blundering as a Trump, and would thus be less likely to create flashpoints. But H. Clinton’s neoliberal-neoconservative policy mix would have been relentless in boxing resistant nations into a corner, and she had surrounded herself with advisers who have contemplated the first-strike use of tactical and battlefield nuclear weapons.

Would we be better off with this smooth, competent, American suprematist organisation as opposed to … well, whatever the Trump organisation is? Not necessarily. We would just feel more comfortable with it, because they are more like us. But they would be willing to serve up death in the tens of millions or more, if that’s what was required to maintain their power — and, so far as Australia is concerned, they wouldn’t care much about which way the wind blows.

Nuclear exchange — by intention, bluff, malfunction or all three — is a certainty under our current global system, and the only rational policy is a steady dismantling of the autonomous systems in place that may cause it by accident — and the ancient forms of sovereignty that will do it by design.

Trump has the virtue of being more transparent in his lunacy, Hillary would have looked the part while doing backroom deals that would shock, so much more than what is going down at the Royal Commission. Real shock, real shocking.

Having to either barrack for Barack’s replacement as either Hillary or Trump was worse than Sophie’s choice. And yes, those missiles, with 50 year old parts and software systems.

Guy, thank you for an interesting perspective. I agree in principle: we know that the nation-state model for human society is Mediaeval in origin and precarious at best, with the ‘nation’ side being eroded by otherwise-beneficial multiculturalism, while the ‘state’ side is under erosion from globalisation and corporatism. And we have no way of knowing how far it can scale under these conditions and remain stable (if indeed it’s stable at its present scope and scale.)

But even less clear is what should replace it, or how that could be sensibly transitioned. You’ve posed the question. What kinds of answers do you believe represent reasonable candidates, and what makes them reasonable?

Trump, Clinton, any US ‘leader’ for that matter, are distractions when it comes to North Korea.

Despite the West’s fascination with all things Western, and the everlasting refusal to consider how ‘the other’ may do things, it’s China and Russia who are running this show on the Korean Peninsula.

It all turned when the admirable Moon took over the reins in the long corrupt South Korea, and the regional ‘Big 2’ recognised a like mind on the matter of national sovereignty.

Not long after he assumed the reins, Moon attended a regional development forum in Vladivostok (around Sept last year). There the Russians laid out a development plan involving Russia, China, South and North Korea, Japan and Mongolia.

That development plan involved around 7 ‘streams’ of activity, from infrastructure, to energy, to food, to water, incorporating all 6 ‘neighbours’.

The North Korean ‘nuclear threat’ did overlay much of what was discussed, and progressed, but the path forward could already be seen, and was recognised (in amongst the usual diplomatic fog).

What we saw late last week, in Korea, is very much a product of what began to gather steam in Vladivostok.

Ironically, or not, the list of places being considered for the Trump/Kim summit now includes Vladivostok.

To anyone too young to remember ancient history, say the Cuban (read Turkish) missile crisis in 1962, it should not be forgotten what was intended by the acronym MAD – utter annihilation of tens/hundreds of millions, who would have been the lucky ones.

Or that other charming feel good, “better dead than Red” – that was still current yea even unto post Reagan.

Have no doubt that la Klingon was just dunky-hory with “be(ing) willing to serve up death in the tens of millions or more, if that’s what was required to maintain their power“.

At least the Drumpfster doesn’t hide his…err, wotever.. beneath a bushel – he wears that thatch.

This Trumpian “victory” (poor word, but meh?) is a puzzle.

I think that a media shoot showing the two Korean leaders holding hands is meaningless. Are we so hungry for a resolution that a photo opp stands in the place of actual progress? Lets see what happens, but for my money in five years time we will be right where we are now no matter who is tweeting from the Lincoln room dunnies.