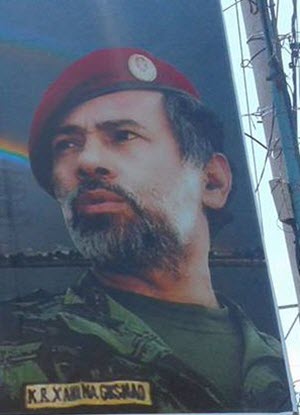

Xanana Gusmao, leader of Alliance for Change and Progress.

East Timor is in for another change of government, less than nine months after the last elections. Xanana Gusmao’s Alliance for Change and Progress (AMP) appears to have secured 35 seats in the 65-seat legislature, ousting the minority Fretilin government which was forced to the poll after having its budget blocked last year.

The elections were largely orderly. Heated political rhetoric raised the prospect of conflict between party members, but there was little reported political violence.

As with the 2017 election, the “Generation of ‘75” (the leaders who arose in response to the Indonesian invasion of 1975) continued to dominate the political landscape of East Timor. This was despite increasingly loud calls for them to move on. Resistance-era credentials were especially played up by Gusmao, with his campaign poster featuring his much younger self in uniform looking defiantly into the distance.

The AMP victory is likely to assure political stability in the tiny half island nation. Fretilin’s leader, Mari Alkatiri, said on Saturday, before the results were known, that he would respect the election outcome. Fretilin’s vote did increase, from just under 30% to around 35%, which marks the first time in over a decade it has been above 30% mark.

Fretilin’s previous minority government partner, the Democratic Party, received 8% of the vote, with a coalition of smaller parties under the Democratic Development Front (FDD) banner looking to take around 6% of the vote. No other parties broached the 4% cut-off for a seat in parliament.

Under the “double turnover test” for new democracies, East Timor has now had four different governments in the space of 16 years. It is, arguably, the most successful democratic state in Southeast Asia — a region which has few consistent democratic successes.

The alliances of parties and the fact just four of them secured seats marks these elections as a further maturation of East Timor’s political processes. That East Timor ran the well conducted elections without external assistance, and also contributed to the growing sense of a deepening of the democratic process.

The fractiousness of the outgoing parliament and the heated language used by political leaders about “coups” and “dictatorships” did give observers some cause for initial concern. In other recently independent post-conflict countries, such language has regularly led to the abandoning of electoral politics.

In 2006, East Timor’s then young and still fragile democracy came close to collapsing following a split within the army and political divisions spilling over into extensive violence and destruction. International peacekeepers steadied the country into its 2008 elections, leaving after the peaceful 2012 elections.

The new government’s main priority will now be working out how to develop the Greater Sunrise liquid natural gas (LNG) field, which it largely controls following a settling of maritime boundaries with Australia. The tiny country will also have to rein in spending ahead of possible delays in the Greater Sunrise windfall, as revenue from existing oil fields starts to dry up and the government draws down on its US$16 billion sovereign wealth fund.

Assuming the Greater Sunrise field can be brought on line soon, this will save East Timor from economic collapse. But the main challenge for any future government is how to establish a sustainable spending program as the country struggles to build a non-oil/gas revenue stream.

East Timor’s elections have given heart to “democratic fatalists”, who believe that democracy will always triumph. But history tells us that democracies, especially ones facing other challenges, remain fragile and prone to undermining or overthrow.

East Timor has taken another important step on the democratic path. It will require sound economic and political guidance to keep it there.

Damien Kingsbury is Deakin University’s Professor of International Politics and Coordinator of the Australia Timor-Leste Election Observer Mission.

That Gusmao-as-Che pic is not reassuring of a settled future.