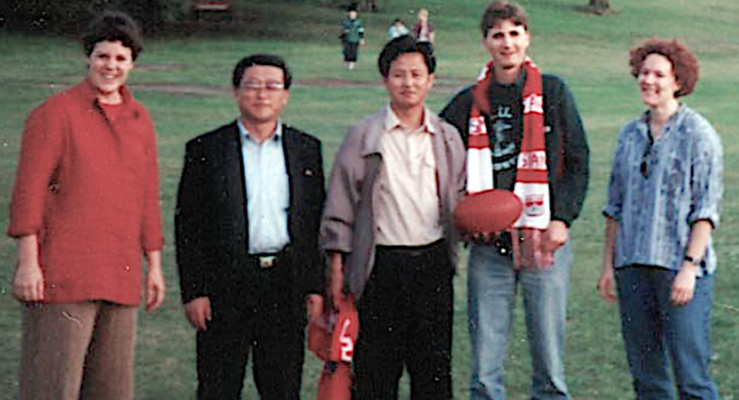

Part of an “official” North Korea delegation visiting Australia in 1999.

As we wait to see if the “The Great Dealmaker” eventually gets slamdunked by “The Supreme Leader” or vice versa, I’ve been forced to contemplate North Korea’s history in the international sphere.

During the period 1975 to May 2000, Australia did not have diplomatic relations with North Korea, although talks were held in 1979, and again in 1990, to re-establish diplomatic ties. This left the very few North Koreans who visited Australia, in a diplomatic no man’s land. I served as an MLC and eventual President of the NSW Legislative Council during this time. Here is my part of the strange story of North Korea’s chaotic and mostly secret relationship with Australia.

Out of pure curiosity, my chief of staff, Yvette Andrews and I had visited North Korea in 1996 on the invitation of the maritime unions. While totally accepting that the regime was authoritarian and often violent, we were not convinced that isolation was a better policy response than reconciliation and reunification. On return, we were conscripted into the Korea-Australia Friendship & Cultural Society, which was run by a famous old Stalinist, Jack McPhillips, who had been jailed during the 1949 coal strike, for hiding the money belonging to the Communist unions in his vacuum cleaner.

Leading up to the Sydney Olympics of 2000, the North Koreans were very keen to make contact with Australia and an “official” North Korean delegation of four arrived in Australia in late 1999. In their diplomatic isolation, my office as President of the NSW Legislative Council became their contact point.

The delegation was mainly here for the Olympics preparation, and showed an alarming interest in the details of our drug testing regime. They struck us as total babes in the wood and seemed to be getting no support at a diplomatic level from Australia. They even rang me to find out how they should get diplomatic plates for their cars. They obviously had little money as they stayed in a run-down motel in Camperdown and worked entirely on their old Nokias.

They brought with them magnificent examples of the beautiful celadon koryo pottery for which they are famous and held two very successful exhibitions in the CBD and Campsie, the heart of the Sydney Korean community. Local Korean-Australians flocked to the shows. Images of the Great Leader and the Dear Leader hung at the head of the room overlooking the exhibition. Each night these photos would be removed and stowed in the safe, or possibly taken back to the motel and placed under Pak Yong Gyun’s pillow. In contrast, magnificent examples of celadon by the great masters were given scant protection.

Yvette also decided to take Choe Yong Jim and Yu Kwang Rim, the two most important official guests to a proper Australian cultural celebration — a Carlton/Sydney Swans AFL game. She convinced them to be Swans supporters, and they sat there stolidly for the entire game. About halfway through the match, Mr Yu turned to her and exclaimed “Number four, very good catching”. Number four of course was probably our most famous footballer ever — the great Tony Lockett himself. Mr Yu clearly got the idea of Aussie Rules. Yvette even took them for a kick to kick in Moore Park after the game where a Sherrin was ceremonially presented.

We took them to Canberra to meet with Labor MPs Gareth Evans and Kevin Rudd who, although surprised, were both very polite and well-informed about North Korea. Mr Pak spotted Alexander Downer in a function room and had to be physically restrained from instituting an impromptu North-South summit.

A few years later, Yvette and I were invited to a North Korean performance in the Sydney suburb of Belmore. Thousands of local Korean Australians attended. The star of the show was a North Korean crooner known as the Elvis of the North. He and his singing partner, a Korean version of Doris Day, were a huge hit, especially when they sang a duet about the reunification of Korea. The entire audience sang along and sobbed.

We forget that Koreans are one people divided by an artificial line for the past 60 years. This was really made clear to us when, just after we returned from Pyongyang we were told that the South Korean consulate wanted to pay us a visit. When the Consul and his deputy arrived, we were expecting to be ticked off. It was quite touching when the only thing they said was “What’s it like in North Korea? We’ve never been there.”

When the North Korean and South Korean teams walked in to the 2000 Olympics, hand in hand, many in the international community were amazed. We were not surprised. We finally understood what the visit of this weird official delegation had been about.

Nice narrative Ms Burgmann but something about what you saw, if not discovered, in the north would have been better.

Superb article. Fascinating!

Good read; hope you’re working on your memoirs Meredith.

That brought tears to my eyes. We in Australia do not know we are alive most of the time and cannot imagine what it must be like to be physically separated from relatives and know hideous things might be happening to them.

While I cannot imagine Trump has any idea about how to go about diplomacy and perhaps the Summit won’t have achieved anything, maybe we should all hope and pray it was a small step towards a better and unified Korea.

We also forget that the US dropped well over half a million tons of bombs, napalm and chemical weapons, razing entire cities and killing over a million civilians.

Yes, nice anecdote from Ms Bergmann, but it seems both sides of politics in Australia are comfortable with perpetuating the notion that diplomatic failure/ all Korean dysfunction is due to an eccentric and despotic N Korean regime.

Korea was the US’s first hamfisted attempt at ideological warfare post second WW, and they failed. Like in Vietnam, a threat of failure unleashed unspeakable brutality from them, as outlined here by Albacore; and it still didn’t work.

So a division occurred and N Korea became diplomatically isolated; while the UN was involved, it was largely the US’s idea (better than defeat?).

The continuing division of Korea is an humanitarian tragedy, and aspirationally most Koreans want it to end. Removing the US spite from any negotiations may help a great deal in advancing that.

Moon Jae-in deserves credit, and is doing all the recent groundwork here.