While we’re bombarded with claims of an “obesity epidemic” and an “obesity crisis” and Australians being manipulated by the sinister “Big Sugar“, Australians are, inconveniently, living longer and healthier than ever, with some worrying exceptions.

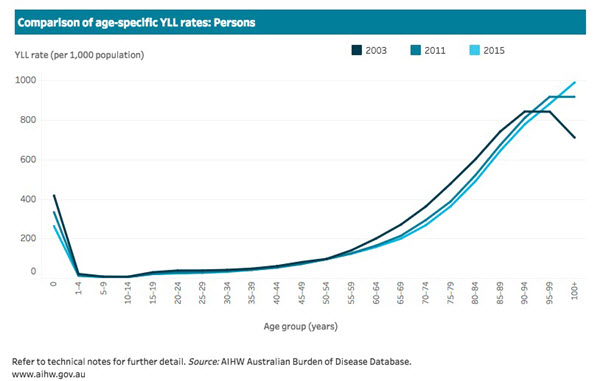

Recent data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare on the “fatal burden” — the years of life lost from individual diseases and conditions — shows that in 2015 Years of Life Lost (YLL) per 1000 population for all Australians fell by 5.5% compared to 2011, as part of a nearly 20% fall since 2003. That means that the average numbers of years of life lost to disease every year, as a proportion of the whole population, has dropped by nearly a fifth since the early 2000s.

In terms of age groups, the biggest gains in recent years have been in 75-90-year-olds, but all groups over 55 have noticeably reduced the level of YLL. Coronary heart disease remains the biggest killer and greatest source of YLL, but has reduced 45% since 2003. Stroke has slipped from second to fourth greatest source of YLL, due to a 42% fall. Breast cancer in women has fallen 26.2% in YLL per 1000 population; bowel cancer has fallen by 24.5% and lung cancer by 15%. Motor vehicle accidents have dropped 45%, while the YLL for type two diabetes — another epidemic we are said to be in the grip of — has fallen by 32%, taking it out of the top 10 sources of years of life lost and down to 16th.

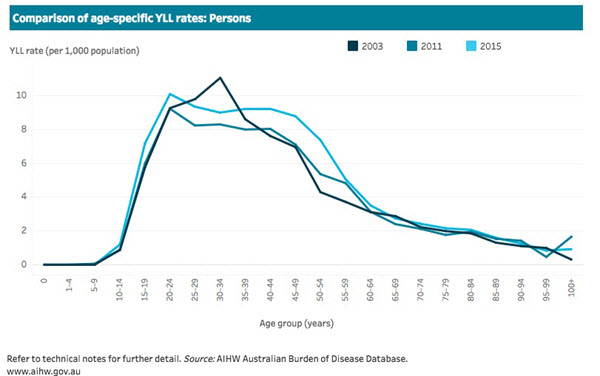

However, the YLL to dementia are up nearly 80%, heralding dementia’s arrival in recent years as one of Australia’s biggest killers. And YLL to suicide are up 11%:

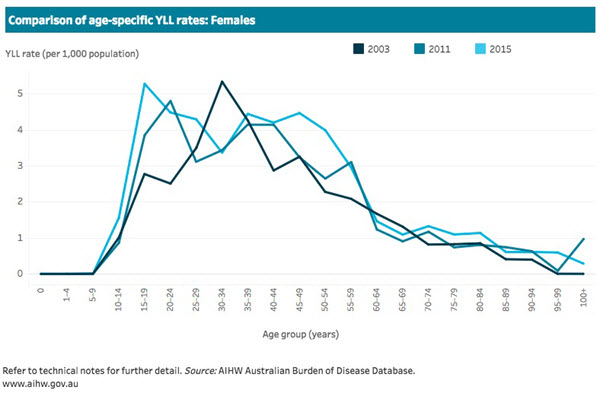

In particular, years of life lost to suicide among females has increased alarmingly; they increased 6.7% for males (who remain far more likely to take their lives) but 27.3% among female since 2003. And the age distribution of male suicide has remained broadly the same across the period, but it has changed significantly for women — and particularly for teenage girls — there has been a big spike in YLLs among 15-19 females.

While the internet has often been the subject of moral panics, it’s possible that this may be related to online bullying; the evidence is unclear.

Years lost is also much higher among low-income earners, with years lost averaging 80% more in the lowest income quintile compared to the highest. Years lost to lung cancer among the lowest income quintile are more than double those among the highest; years lost to most other cancers are much more similar between quintiles, except liver cancer. Years lost to homicide are also much higher among low income earners. Average years lost across the lowest quintile have fallen 10.6% since 2011, but that’s not as much as the fall for the wealthiest quintile, where years lost fell 13.5%.

Remoteness is also a major contributor to years lost, obviously reflecting the persistence of poorer health outcome for indigenous communities (although indigenous people in urban areas have poorer outcomes than non-indigenous Australians, and non-indigenous people in remote areas also have poor outcomes). However, the biggest falls in years lost have occurred in remote and very remote communities: for very remote communities, the average of years lost in 2015 adjusted for population was down more than 17% on 2011 levels; in remote communities, down over 15%, compared to a fall of 12% in major cities, showing health outcome in relation to fatal disease improving faster in those communities than in metropolitan areas.

The latest data from AIHW complements that from a study two years ago comparing 2003 and 2011 data, that found that not merely were Australians living longer, but were doing so in better health.

Reach Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Suicide in Gamblers Linked to Increased Psychiatric Disorders, Lower Rates of Help-Seeking

More Vigilant Screening for Signs of Suicide in Pathological Gamblers Needed

Deborah Brauser

Dr. Boyer reported that pathological gamblers account for 5% of all suicides, and past research has shown they are 3 times more likely to commit suicide than nonbetters.

December 3, 2010 — Pathological gamblers who commit suicide are significantly more likely than their counterparts who do not gamble to have personality disorders and much less likely to seek help, new research suggests.

Although researchers found both groups of gamblers who committed suicide had psychopathologic conditions, the compulsive gamblers had twice as many specific personality disorders and were 3 times less likely to seek mental health help before their deaths.

“It was important to find out that the association with suicide was not only related to pathological gambling but also to the presence of many other psychiatric disorders, such as depression,” coinvestigator Richard Boyer, PhD, from the Center de Recherche Fernand-Seguin of Hôpital Louis-H. Lafontaine at the University of Montreal, Quebec, Canada, told Medscape Medical News.

“This study was a must. In Quebec, and I think in the world, this was the first time that this issue of the risk of suicide among people who gamble a lot was looked at in this way,” added Dr. Boyer.

The study was published in the September issue of Psychology of Addictive Behaviors.

Years lost to … : what another wonderfully idiotic P.C. term. The obvious question is “Just how are “years lost to ..” calculated? It is all very well to subtract the life expectancy from the age of death for a male or female but such is NOT and cannot be the definition or the description of “years lost to .. whatever. Conditional probabilities would have to be taken into account such as mis-adventure from walking the dog to parachuting to trail bike riding or even driving to the relatives – for a GIVEN individual and NOT the average individual; a non-trivial undertaking even with Baysian Priors! Otherwise : just enlist suicide or homicide as descriptions. The intention will be a lot clearer and a LOT more accurate.

As to the article two questions present themselves; viz., : is suicide (fundamentally) a psychological condition or a sociological condition. The ASSESSMENT of suicide is gong to turn upon the answer to this question. After that question has been resolved then we can build our “tree diagram”.

Although, credit where it is due (and to be fair) the graphs are interesting. It would be nice to play with the data for an afternoon and ascertain of there is any statistical difference between 2003 and 2015 with regard to the charts . It would seem not (by eye) but one would have to crunch to data to be sure.

What exactly did Big Nanny do to BK, in his formative years… or last week, whatever, that causes him to pound out such splenetic, swivel eyed articles?

Somebody should plot out a timeline & graph – perhaps it is something to do with phases of the moon?

I don’t regard myself as a reporter’s bootlace but I can undertake research. Reflecting upon the comment from AR, it occurred to be that a superior article could have been presented appealing to the following sources (that are by NO means exhaustive)

The first consideration is that the phenomenon (of increasing rates of juvenile suicide – among females in particular) is NOT confined to Australia. In conjunction with (shall we say) “integrated factors” – possibly being associated, inter alia, with globalisation, – the phenomena seems to be world wide or at least 1st World-wide.

For the USA there is this article

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/04/22/474888854/suicide-rates-climb-in-u-s-especially-among-adolescent-girls

For the UK this article confirms the general theme

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-health/11549954/Teen-girls-Suicide-kills-more-young-women-than-anything.-Heres-why.html

but is contradicted, somewhat, by this article by the Office of National Statistics.

https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/suicidesintheunitedkingdom/2014registrations

This rather comprehensive review for Europe is also interesting (and the interested reader, with some assistance from Excel, can summarise it for himself).

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Being_young_in_Europe_today_-_health

Then there is (good old) Wikipedia.

I’ll leave the above to a qualified reporter to summarise and conjecture social motivations for the change in the trends. However, not being able to resist “taking the plunge”, the realisation that Gen Y & Z are not going to “have it” as good as the boomers, or indeed Gen X, may (just) be a factor.

Decades of “dumbing-down” the primary and secondary syllabus was to have had the consequence that life would (in some ill-defined sense) become easier for future citizens. Yet it is all too apparent that the education programme (of quite some number of years) has not prepared young people for the obvious challenges that exist from now to (e.g.) 2050 or 2060).

Years lost to the grog doesn’t get much mention. Where I live alcohol is the biggest killer of men aged 40 to 70. It gets recorded as many different causes when I ‘ve watched as they drink themselves to death.