On June 20, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order bringing to an end the practice of separating undocumented migrants from their children on the US-Mexico border and announced, with typical precision and accuracy, “It’s been going on for 60 years. 60 years. Nobody has taken care of it. Nobody has had the political courage to take care of it. But we’re going to take care of it.”

The crisis is far from resolved — families can still be detained, just together; children are still separate from their families (who in some cases don’t know where they are) and Trump has mused on henceforth removing undocumented migrants’ right to due process. But given the apparent intractability of the administration, the executive order counts as a major win for opponents of the policy.

Of course, the similarity between the new US approach and that long employed in Australia has been noted by many in the media — despite claims to the contrary, there are still 200 children in asylum seeker detention both on and off-shore and, while the details are opaque, Deborah Zion in The Conversation says families are still regularly separated. Trump’s executive order came about after sustained pressure from the public and media to renege on the policy. How did they achieve in roughly a month what refugee activists in Australia have failed to do in nearly 20 years?

Location

The Australian government can send asylum seekers (even those ultimately successful in their application who offend in the community) off shore, to Australian territories like Christmas Island, Nauru and Manus. It can rely on a client state like Nauru to make the process of applying for a journalists visa prohibitively expensive, or just deny them to all but friendly journalists. The Trump administration has no such luxury.

Though the separated families have been scattered across the country — in some cases in secret locations — they are accessible enough for lawmakers, the media and eventually the first lady to visit, and their accounts, not to mention pictures of children in cages form part of the movements against the policy.

Media Outrage

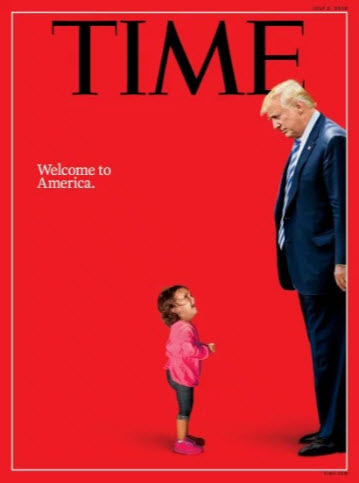

But it is not simply a case of access. The policy has been met with unanimous (aside from Trump’s mouthpieces at Fox) outrage; even aggressively centrist publications such as The Economist and Time have published unequivocal condemnations of the policy.

The Time cover, showing a smiling Trump looking down at a weeping Honduran child, became instantly iconic.

While there has been no shortage of serious, thoughtful and thorough reporting on asylum seeker policy in Australia there has been no similar concentration of criticism.

Partisan differences

The Trump rhetoric around immigration has been to pin the culpability on the Democratic Party — Trump is merely enacting laws that the democrats refuse to change. While the Democrats under “deporter-in-chief” Barack Obama were not the greatest friends of undocumented migrants, the accusation wasn’t true. They have been publicly united in their opposition to the policy.

In Australia, however, there is, for the most part, agreement on the issue between the major parties. Indeed, the current arrangement was engineered by Labor’s Kevin Rudd, in an attempt to wedge Tony Abbott on his trademark policy leading up to the 2013 election. Any hint of movement towards a less strict policy on Labor’s side leads inevitably the accusation that boat arrivals would immediately begin again under a Labor government. This has hitherto proved an effective cudgel, preserving the bipartisan commitment to “stopping the boats”.

States

A small but key victory, both symbolic and practical, for opponents of the separation policy is that it relies at least partly on resources controlled by the individual states. Governors in eight states — including New York, North Carolina and Virginia — all announced they would either recall or withhold their national guard troops from the southern border until the policy was abandoned. Largely these are Democrat state, but two Republican governors (who are coincidentally facing elections in November) in Maryland and Massachusetts also reversed their plans.

While state governments (notably Victoria) in Australia have stepped in to fill gaps left by the Commonwealth in asylum seeker support, Australia’s states exercise no such control over the forces (either federal or private) that allow the detention to continue. Of course, given the bipartisan agreement over the policy, it wouldn’t matter much if they did.

The difference is that in America a lot (most?) people know people who came to America as illegal immigrants or who are chidren of illegal immigrants. There’s a human face on it. They are “us” not “them”.

The number of “illegal maritime arrivals” to settle in Australia is a drop in the bucket. To Australians they are definitely a “them”

Look at how gay rights and then marriage equality were won. Story after story from socially conservatives people saying they used to be anti-gay until discovering a loved relative or friend or co-worker is gay and realising hey, gay people aren’t the devil.

They have a bill of rights.

The people (residents) they are deporting have an economic value (they probably worked for very low wages). Business’ and landlords are probably pissed off.

The fallacy as presented is that the initiative is “the last word” – so to write. The pragmatic view is to “see where the decision goes”. If the matter remains “controllable” then good and well. Should the matter become ungovernable then

the decision will be reversed in a tweet – with the injunction “I told you so”.

As to “human faces” it is less a matter of identity than of acquiescence but not necessarily tolerance; homosexual marriage is a case in point. As to a Bill of Rights – such a document establishes nothing. South Africa has such a document (google the crime stats) and similarly as signatories to this UN convention or that convention. As an aside damn all remains of the Magna Carta.

The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) on human rights is a UN initiative that started in 2011. Israel withdrew (after criticism) in 2013 (and hasn’t been back). Then there is Mauritania where slavery was legal until 2007. As for “freedoms” in the USA the place has had a Bill of Rights since 1789.

Unlike the US Rupert’s FUX News has too little competition here and too much say in our politics – a foreign body interfering in our own politics – but will Turnbull treat them like other “foriegn interests” with similar m. o?

NFL.