Unless you’re a regulation nut, you won’t know what the enforcement pyramid is. But it’s at the heart of the framework Australian governments establish to protect consumers. And in financial services, it’s completely useless. We need a new regulatory shape.

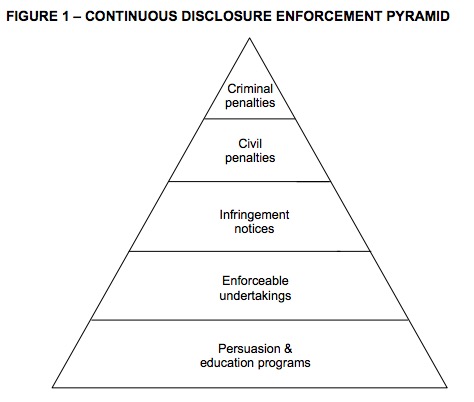

The pyramid has self-regulation and what’s called co-regulation at the bottom, in which companies police themselves or report breaches to a regulator or are subject to a complaints mechanism, then there are mid-tier powers for more substantial breaches — enforceable undertakings, or licence conditions, or “speeding ticket” infringement notices. Then, for more serious breaches or repeat offenders, there are civil penalties, then at the very top, criminal penalties that can see large fines and, potentially, jail time or the corporate version thereof — removal of licences or prohibition from trading. This image, from a paper by Aakash Desai and Australian regulatory guru Ian Ramsay, illustrates it:

This has been the regulatory approach for financial services: in addition to consumer complaints to regulators, banks and other financial service providers are expected to police themselves and report breaches to regulators, who — theoretically — may investigate themselves and respond with escalating sanctions.

But as is now apparent, financial services regulation isn’t a pyramid. It’s more like a very, very thin trapezoid made up entirely of the bottom tier of self-reporting. The constant evidence from the royal commission has been the obstinate refusal of the consumer finance regulator ASIC, or the prudential regulator APRA, to take any kind of strong enforcement action against big banks or insurers guilty of serial and major breaches of the law. But a report from ASIC yesterday illustrates the extraordinary contempt with which those companies treat their self-reporting obligations.

The report revealed it takes big institutions an average of 2145 days — or almost six years – between the first breach and the first compensation payment to customers. And according to ASIC, “the major financial groups took an average of 1726 days (median: 1148 days) to identify an incident that was later determined to be a significant breach”. They undertake long investigations — 150 days — before they report breaches, and one in seven breaches is reported later than the legally required 10 days.

And this is quite deliberate. One of the big banks, Westpac, is able to compensate people significantly more quickly than the others. And smaller institutions investigate and report breaches and compensate people much more quickly. The big financial institutions simply refuse to regulate themselves properly, despite having billions more in profits than smaller rivals who take their regulatory options more seriously.

It’s clear that the pyramid needs to be ditched. Self-regulation and co-regulation have demonstrably failed. The entire bottom tier of the pyramid needs to be removed. The base must be mid-tier regulation — the automatic infringement notices, enforceable undertakings. Then civil penalties and criminal penalties, with a regulator far readier to resort to those measures. The pyramid shouldn’t taper anywhere near as much as it currently does.

And there’s a way to compel banks to speed up compensation and force them to co-operate more readily with inquiries by regulators. In response to a complaint, the regulator makes a preliminary estimate of what it believes the compensation for a breach, if found, should be, then compels the bank to hand over that sum. And that’s not returned until the bank resolves the complaint satisfactorily, with the regulator keeping the interest. ASIC concludes that the delays they examined related to complaints and breaches worth $500 million. That would be a substantial incentive for banks to speed up their dilatory internal processes.

The only problem is that the government has imposed a peculiar limitation on the royal commission in the terms of references, which includes this:

The Commission is not required to inquire into, and may not make recommendations in relation to macro-prudential policy, regulation or oversight.

The thrust of this is understandable: to avoid bringing into question the prudential regulation of the sector, especially banks, and the overall objectives of prudential regulation and monetary policy more generally. But the changes needed to get rid of self-regulation and get the enforcement framework working again are likely to relate very clearly to macro-prudential policy and oversight. We’ll find out on Friday, in the commission’s interim report, how Kenneth Hayne proposes to resolve that tension.

I completely agree. I cannot think why any sane person would think that self-regulation would work, particularly given the many examples of when it does not.

However, it is not just APRA and the ACCC – where was Fair Work when the Seven 11 workers were being ripped off? Why was it left to the ABC to expose this? What were they actually doing? Another example is the body supposed to oversee and regulate the aged care sector – again MIA.

I am sure there are many, many examples of employees and management of these bodies not doing the work we are paying them to do.

No humble cleaner or manufacturing worker could get away with not fulfilling their duties.

The government will do what is necessary to ensure that there will be no criminal convictions for the crooks. The Icelandic bankers who were jailed will no doubt be making arrangements to get their CV’s polished and sent to our big four legal mafias.

The Productivity Commission was right when it said the four pillars banking policy should be put in a cupboard. We need a genuinely adversarial banking ombudsman (not the bank appointed wimps who are there now) who can name and shame with full Government support and then demand the regulators take legal action with massive new penalties, we need a whistleblower incentive scheme like they have in the United States and we need to go back to the firm separation of “banking retail” from “banking speculative” investment and other financial schemes.

Could not agree more, excellent suggestions. Unfortunately both libs & labor are the bankers friend & no one can expect any change as these corporate thieves continue on their merry way to even bigger profits at our expense.

“Mate. You can self-regulate – we’ll take care of the dog. Wink wink, nudge nudge.”

OK, so I actually AM a bit of a regulation nut. Sufficiently at least to be familiar with (and to have used) such pyramids. First: these pyramids originally came out of empirical research on how regulatory agencies do their jobs. Particularly, very poorly funded agencies with limited sanctions at their disposal. (See Hawkins on UK Environmental Pollution agents wielding the huge stick of 100 pounds maximum penalties, for example). In other words, as a description of how agencies function, they reflect the realities of choices having to be made. Secondly: to the extent that these pyramids have a normative function – that is, serve as a guide to what should be done – it is a grave mistake for any regulator – or anyone else – to assume a necessary vertical progression from bottom to top. Better regulators always establish compliance, enforcement, and sanctions policies that reserve the right to start as high up the pyramid as necessary, depending on the nature of the breach and its consequences. Think OHS regulation: the first time offender that fails to put in place systems to save a life usually will – and should – go straight to the top.