Former ABC chair Donald McDonald made a significant point on Thursday about his time at Ultimo, though he otherwise declined to comment on Justin Milne’s extraordinary attempts to have ABC journalists sacked. Speaking to ABC Sydney, he said:

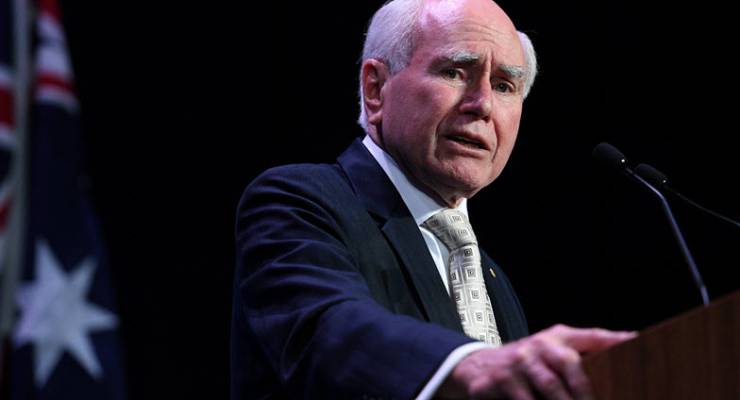

Ministers were on occasion unhappy about some report some coverage, they were always prepared to put their complaints in writing and they were addressed in a thorough way… On the day my appointment was confirmed, John Howard said to me ‘I will never speak to you about the ABC, I will never raise the ABC as an issue with you, if you want to talk to me about the ABC contact my office, make an appointment and come and we’ll formally meet and discuss it.’ Which we did 3 or 4 times over funding issues. But never did he speak to me about a program either happily or unhappily.

There’s no doubt that the Howard government prosecuted a war against the ABC. The complaints launched against the broadcaster’s Iraq War coverage by Communications Minister Richard Alston initiated a period of open hostilities between the government and the broadcaster. But it was a war prosecuted in a very different way to that undertaken by the Turnbull government, as McDonald’s remarks show.

For a start, complaints were made in writing by ministers about programs. Alston made 68 separate complaints about the ABC’s coverage of Iraq — in retrospect, not exactly the kind of issue conservatives would like to brandish against the national broadcaster. But they were handled like any other complaint: by the ABC’s complaints review executive. In fact, much of the conflict between Alston and McDonald and then-managing director Russell Balding was over the complaints-handling process itself, rather than the substance of the complaints, and led to months of toing and froing between the minister, the ABC and the Department of Communications over revamping the process to increase its independence.

Contrast that with the fact that Milne wasn’t even interested in the government’s complaints being referred to the ABC complaints area, as Michelle Guthrie said they should be — he just wanted journalists sacked.

McDonald’s other points was that contact with the PM was formal. Howard declined to pick up a phone, or dictate a letter, to McDonald to complain about programming; the only contact was over budget issues, and it followed a formal process.

Current Communications Minister Mitch Fifield has denied this, but until Malcolm Turnbull there was no tradition of ministers and Prime Ministers picking up the phone to complain about ABC programming. As McDonald says, Howard never raised programming with him, full stop. Alston, Daryl Williams and Helen Coonan may have spoken with MDs and chairs informally — Alston attended an ABC board meeting when he decided to start trying to broker a peace with them — but contact was primarily in writing. And Stephen Conroy called Mark Scott precisely once during his tenure as Communications Minister, about the politically loaded and deeply divisive issue of the scheduling of Doctor Who. But under Turnbull and Fifield, the practice of government ministers casually calling and texting chairs and MDs of both the ABC and SBS to complain about programs and journalists has exploded.

The problem with this is that there is thus no paper trail of government attempts to influence the ABC. The Alston-McDonald correspondence over the Iraq War complaints sits in the Department of Communications’ files. Both sides followed due process. That process has been ditched by Turnbull, meaning there is now far less transparency about the Liberals’ war on the ABC.

Maybe if Milne had insisted that Turnbull and Fifield follow the Howard example and keep things formal, he wouldn’t have been compelled to resign.

Bernard Keane was manager, National Broadcasting, in the Department of Communications from 2000-05.

A bloke can only do so many things at once! Howard had his hands full corrupting the ADF at the time. Tony, Malcolm and Scott have taken up the mantle with regards the ABC, the AFP and whatever remains of the smoking ruins of the APS.

I’m unable to stomach the thought that John Howard could ever teach us anything worthwhile He’s a big Ramsay supporter, after all. His “reign” over Australia was disastrous for this country.

All Keane is saying is this Liberal government is worse than the last. That isn’t outside the realm of possibility. It isn’t like Howard was literally Hitler.

I agree, Howard wasn’t threatened by the ABC – he just didn’t give a damn about bad press.

He could afford to be. When it came to the ABC, he had Richard Alston as “The Butler” (did it), and Coonan as “Lady Macbeth”?

Turnbull’s approach shows the need for caution when business entrepreneurs enter politics. They are accustomed to giving orders and having their way, essentially answerable to no-one provided they are making money.

Fantastic comment and thoroughly agree.

King Rupert wasn’t an eighth of an inch of completing his Final Solution back then – elderly, unemployed, poor, sick, disabled and queer living in slums and wall-to-wall media dominance on TV/print/radio with the middle class.

He’s so close now he can almost smell it, so going in for the kill.