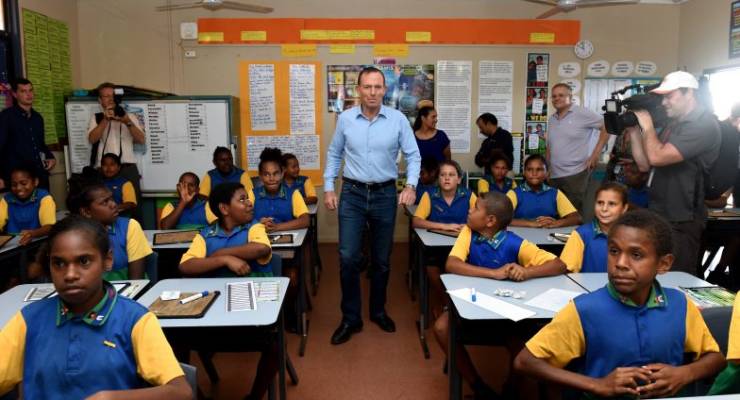

If there is anything Tony Abbott wants out of his consolation prize as Special Envoy for Indigenous Affairs — aside from publicity — it is to reinforce English-only instruction for remote Aboriginal kids. It began with his declaration on Sky News that Aboriginal kids must “learn to think in the national language”: a message he has reproduced, just as ham-fistedly, everywhere in his fly-in fly-out tour of remote schools.

But a key reason his comments are so absurd is that the vast majority of remote school in Northern Australia do teach an English-only curriculum, after a near two decades of policies designed to undermine bilingual programs in the Northern Territory. Abbott’s policy prescription of more English, always English has been the diet of remote schools since the late 1990s, and it has achieved very little of the improvement in English literacy that it supposedly is designed to.

Today, only seven schools teach a bilingual program combining an Aboriginal language and English as languages of instruction.

Debunking the “more English” myth

This is despite the fact that most Aboriginal people in the NT speak an Aboriginal language or languages at home. In remote areas, there is still little exposure to Standard Australian English, so the majority of Aboriginal children in the remote NT are coming to school as speakers of their local language.

Abbott’s base logic is that more English equals better English (married with his fetish for “structure, discipline, repetition”) is a deeply discredited one. Research shows that learning to read in your mother tongue and transferring those skills to another language later is the best method for producing biliterate bilinguals.

Yet stigmatising Aboriginal languages — and by extension, their speakers — remains the order of the day.

Next year will mark twenty years since an attempt by NT government to take away all funding and give it to English as a Second Language (ESL) programs, which, after outcry, produced a compromise “two-way education” model. This October marked ten years since the introduction of the First Four Hours policy, mandating teaching in English for the first four hours of the school day (it was quietly dropped in 2012).

Officially, today’s policy is that schools that have the qualified teachers to run a bilingual program are able to do so, supposedly without hindrance from the NT government. But this supposed permissiveness obscures a generalised hostility and near total lack of support.

Lacking genuine structural support

Simply “having” the qualified teachers has become more and more difficult for a myriad of reasons: the qualifications required have gotten more difficult to attain for Aboriginal teachers who may not have gone to high school, there is almost no on-site training, and the organisation mainly responsible, Batchelor Institute, appears to be in rolling crisis.

In fact, two schools, in Yuendumu and Lajamanu, both Warlpiri-speaking schools, fund the resources for their bilingual programs through the Warlpiri Education and Training Trust (WETT), funded by mining royalties and associated with the Central Land Council. In other words, the community is devoting millions of dollars of their own money just to ensure the program’s survival. They also provide language resources to the schools at Nyirripi and Willowra.

Alongside that, schools now have what’s called “global budgeting”. This means that the local principal is responsible for all funding decisions, and as one NT policy-maker describes to me “this is the real sharp pointy edge of how much people really appreciate and value the contribution that Aboriginal people make in the school”.

Without assured principal support, bilingual programs are in constant danger. Non-Aboriginal principals reportedly regularly arrive in bilingual schools without knowing they are bilingual, and they and other non-Aboriginal staff are under no obligation to learn the local language. With perpetual outsider turnover in remote communities, there is also a revolving door in teaching approach (as one former teacher at a bilingual school put it to me, “I’ve had more principals than I’ve had roast dinners”).

While the Labor government has funded a position within the department to head the bilingual programs, according to an NT government source, funding for Noel Pearson’s Direct Instruction programs was $32 million in 2017, while funding for bilingual programs was just $3.2 million.

Arguably, Abbott’s approach to education is just the latest manifestation of the neo-assimilationist turn in Aboriginal policy, whereby remote communities must somehow be made “viable” in the market economy, or face sanction and neglect from government.

“All of the education funding today has narrowed down to these really clear outcomes that are all job-related — but they don’t actually create jobs in remote communities”, one NT policy maker argues.

Amidst a growing public discussion about language revival, and decisions to teach Aboriginal languages in LOTE programs in Victoria and New South Wales, there is a markedly different approach to the future of Australia’s living Aboriginal languages and the people who speak them.

Wendy Baarda has been a teacher in Yuendumu since 1973. She told me, “There’s an old saying—they think if you squeeze an Aboriginal person hard enough, a white person comes out. Well, today the squeeze is the hardest I’ve seen it in my lifetime”.

All Abbott wants to do is squeeze even harder.

Amy Thomas is a lecturer and PhD candidate at the University of Technology Sydney where is she is also a 2018 Shopfront Community Research Fellow. Her research concerns education, language, social movements, and Australian history.

Mature adults can become fluent in languages they didn’t learn in infancy. Abbott doesn’t need to go very far to observe that. His friend and colleague Mathias Cormann didn’t speak a word of English until he was in his twenties. You can laugh at Cormann’s accent, but he’s fluent in English and seldom if ever gets a word wrong. Although I’m Australian I have had the same experience myself in a second language, as have many immigrants to this and other countries. There is no educational reason why Aboriginal children shouldn’t learn to read and write in their own language first and then go on to master English. Abbott may have other reasons for enforcing English but they aren’t educational.

You’re absolutely right Rais. My mother, a Toowoomba girl, learnt to speak both Dutch and Indonesian fluently after marrying a dutchman after the war. But there’s no reason languages can’t be taught side by side. As a child at primary school in Holland, I was learning Dutch, English and French. It was normal. You’d be hard pushed to find a person in Holland today who doesn’t speak fluent English and often French or German as well.

What is it about people like Abbott, some kind of remnant of conservative, old school British colonialism? Whatever it is, this type of backward thinking should have no place here and certainly not when applied to Aboriginal schooling. If anything I would think knowing and speaking your native language is a human right.

It is a very great shame that Oz/NZ/Canada/UK/USA are mono-lingual. Spanish sign-age is appearing in many parts of the USA. I’m the first to advocate languages being taught in primary school and the earlier the better. The matter here is different and the agendas are different. I’ve read essays arguing that Aboriginal children be insulated from English until high school.

Appealing to my own school days – Maori kids spoke Maori by osmosis. Some of the white kids picked up Maori by osmosis – but that practice was not really encouraged. That written most white kids “graduated” from primary school with about 50-100 words of Maori.

Pity that by the end of year 10 students are not acquainted with a half dozen Greek or Roman plays along with a a hundred words or so of either language. Just from the exposure of ancient plays discussions on policy (with some grounding in human nature) would improve.

Sorry to say; this was inevitable giving this zealot a job that’s not only wildly inappropriate but yet again dismissive of Aboriginal voices. The PM’s tactic to try and keep Abbott busy and minimise his trouble making is even more destructive and insulting; using Aboriginal people as his political pawn.

Makes you wonder what other inappropriate jobs they have lined up for him once he flunks out of this one.

Amy’s article raises many interesting points that I would like to see explored further. Every pronouncement from Tony Abbott since his appointment reeks of a lack of empathy with Aboriginal people living in remote northern communities and their situation. He wants to punish parents for the non-attendance of their children – what does he know of their life of poverty, of poor health, of constant funerals of close kin, of incarceration of young people for sometimes trivial offenses? What does he know of the contact history and the miserable treatment of the children’s grandparents and great grandparents as their land was taken for pastoral properties, their cheap labour exploited and their herding into settlements where almost total control of all aspects of their lives was enforced? I suggest he take a closer look in some of the school classrooms and then ask himself if he would have been happy to have had his daughters attend every day.

Tony Abbott is a white man with a traditional Australian education – he knows what is best. Just ask him.

What a great article, Amy.

And I agree with all the comments here. Abbott’s approach and the policies set in place towards Aborigines is just an extension of white man imperialism. The English language is fine but never at the expense of their traditional languages and culture. Abbott should take a leaf out of the Aboriginal culture book and understand concepts like sharing, caring, conservation and giving. I would gladly live under an Aboriginal govt than a western imperial govt based on exploitation and greed.