Scott Morrison is hinting he will cut Australia’s permanent migration program. This sounds like it will take pressure off Australia’s infrastructure — but will it really?

The way migration is defined means its measurement can lead you to weird and surprising results. For example, the government’s “migration program” includes 186,515 visas in this financial year. But many of the visas go to people already in Australia. This is “migration” in a legal sense, not in a “moving to Australia” sense.

If we’re going to fight about traffic congestion, we need to keep this in mind. After all, what kind of visa you have won’t change how much space you take up in the morning commute.

Hundreds of thousands of people are moving to live in Australia without migrating in a legal sense. Our temporary migration program is a whopping thing that rarely gets spoken about.

To avoid getting befuddled by ScoMo, we need to understand what we’re talking about. If we don’t understand what a category relates to, the numbers in it are meaningless. All the experts I read and spoke to agree the numbers are confusing, and at times even misleading. This is a conceptual minefield, so let’s tip-toe through it together.

There are three categories to think about:

1. Humans in Australia today

The number of warm human bodies in the country seems like a good simple measure of population. Tourists, students and temporary workers would be counted, while outbound tourists and anyone with an Aussie passport living in London or Tokyo would not.

Tourism makes a surprisingly large difference to this measure and its seasonal spikes depend mostly on us, not foreign tourists. Last January, more than 1.3 million Australians were away overseas on short trips. (No wonder traffic is so much kinder in summer.)

In the last year, Australians spent a collective 500,000 years overseas on trips of less than two months. Another way of putting that: without outbound tourism, the population would be half a million people higher on any given day. (Inbound short-term tourism added 300,000 people to Australia’s population in the last 12 months.)

This is a good statistic to start with because its scale puts everything else in perspective, and because you will not find anybody arguing for or against tourism in a population context.

Managing population pressures by giving Aussies an extra few weeks’ leave a year to spend in Bali might legitimately make a difference to traffic (and be popular!) but it doesn’t feel like a serious population policy.

And, of course, tourists don’t compete for schools or to buy homes. (Although they do compete to rent real estate, and since the advent of Airbnb they compete in the very same markets as residents.) Tourists use infrastructure — but not in the same way locals do. They might be on the road, but not usually at peak hour, and they might be in the hospital, but probably only the emergency department.

When we talk about population policy, we normally refer to managing the number of people who live here. But even that category has to be broken down further to be understood.

2. People who live here

The second category is people “living” here — defined since 2006 as having been in Australia for 12 months out of the previous 16. This is where Australia’s temporary migration program does a great deal of work with little scrutiny.

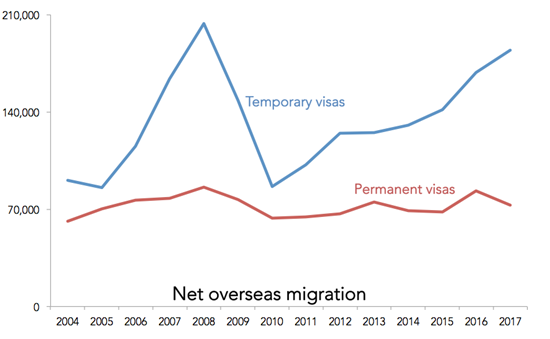

One thing stares you in the face when you look at net overseas migration due to temporary visas: arrivals are higher than the departures every year.

If temporary visas worked like I imagined, the net inflow would be about even. Instead, net overseas migration to do with temporary migrants is huge every year — an average of 133,000 a year in the last 14 years. Temporary visas have had more impact on net overseas migration than permanent visas each year in that period, and the gap has risen over time. It is now more than double.

More than 184,000 net temporary visas were granted in 2017-18, (322,000 arrivals and 137,000 departures.) This figure is counted when people arrive though, and it does not include any visa transitions, which means it can be misleading. (Australia’s population stats are a mess. I know the ABS is underfunded, but if migration numbers were something the government really wanted us to know, they might have made things clearer.)

These temporary migrants make up a substantial shadow population in Australia. Many of their lives are contingent and vulnerable. When we eat cheap food or get an Uber, we depend on their labour, but they do not enjoy all the same rights and protections as other Australian residents.

3. Citizenship/permanent residents

Then you have a final question: who has citizenship, or a visa entitling them to Australian permanent residency? According to Home Affairs, they are planning to hand out 186,515 permanent visas in 2017-18 and 2018-19.

But many of these people will not be coming from overseas. In the net overseas migration statistics, you’re looking at 93,900 permanent visa arrivals and net overseas migration of 72,000. So when Scott Morrison starts hinting at a cut of maybe 30,000 here, it’s not going to make much difference out here in the real world.

Note also that this category might be the least important. The right to live in Australia does not mean you’re adding to population. My sister carries an Australian passport but lives in London. And don’t forget the Kiwis. Every New Zealander has the right to live in Australia. Luckily they mostly stay over there…

It serves Scott Morrison’s purposes to keep us in the dark on what really matters in migration levels. Shedding even a bit more light on immigration is difficult, but well worth it.

“It’s poor long term planning, not the size of the population, that’s the problem”…

http://theluckygeneral.biz/2018/11/21/its-poor-planning-not-the-size-of-the-population-thats-the-problem/

Good article more info and analysis of the numbers please particularly when big numbers are thrown around. I also wonder where are the 40,000 Syrian refugees that Tony Abbott said Australia would accept?

Mozzie, ‘misleading’? Who’d believe that? …. “Emissions”? “Sri Lanka will take care of the refugess we return”? “Labor’s negative gearing policy decimating the economy and your home value”? “Sacked from previous jobs for being too good”? ….. “The PMship sailed into my lap.” …….

More proof that underfunding government agencies (“efficiency”? dividends) was a very bad idea.

I often wish that the ranters who complain about being swamped bythe 50,000 boat people over the 6 years of Labor would compare that to the 1.25M immigrants over the same period.

This is without reckoning – because it is structurally impossible, almost as if deliberately – the 457 “temporary” workers & 676 overstayers.