The ACCC’s preliminary report on digital platforms — or Google and Facebook, mostly — received extensive attention from both the national newspapers today. This reflects not merely that this area is the intersection of two of the biggest issues in contemporary capitalism (market dominance and exploitation of private information), but that Google and Facebook are now the 800-pound gorillas in a market that Nine and News Corp used to dominate.

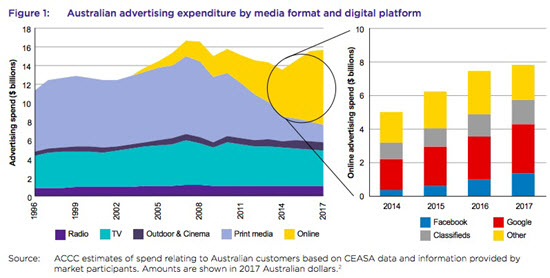

Australia’s two biggest media companies, now dwarfed and monstered by the digital giants, are desperate for more regulation to hem in Google and Facebook and reduce their capacity to keep taking advertising revenue. Online advertising now dominates Australian advertising revenue (it is 51% of all ad spending; TV is now just 24%) and in 2017, 38% of online ad revenue went to Google and another 17% to Facebook.

This has happened because they claim to offer advertisers a product traditional media never could: ads that will reach exactly the people most likely to buy your product. No more costly TV ads that play to audiences 95% of whom have little interest — go straight to the 5% most likely to buy. The digital giants can do that because people have handed personal information to them, and they and other companies have vacuumed up information we haven’t given them but is available from other sources. Our online behaviour is far more revelatory of ourselves than what we actually say.

The ACCC is sceptical that it works quite as perfectly as that. It finds that “advertisers are unable to verify for themselves whether advertisements on Google and Facebook are delivered to their intended audience”. That’s something legacy media has been eager to seize on:

Media businesses that compete with Google and Facebook for the supply of advertising opportunities allege that the unilateral verification and measurement carried out by Google and Facebook compares unfavourably with what they consider to be objective sector-wide measures applicable to traditional print and now online publications and commercial TV broadcasters.

Well, they would say that.

Google and Facebook say there is already independent verification. But the ACCC wants to consider the issue further, noting “it is not clear whether the current terms on which third-party verification providers have access to the Facebook and Google platforms enable them to carry out a reliable and fulsome [sic] audit of relevant ad metrics and measurements”.

The problem for a regulator like the ACCC is that the digital giants’ business model is difficult to regulate; their market dominance is derived from people’s willingness to surrender their data freely, in exchange for the perceived value of being able to look at your sister’s baby photos or find things online. The ACCC’s response is to propose regulations that would try to make the downsides of the deal with the devil that is using Google and Facebook more apparent: notifications that are “concise, transparent, intelligible and easily accessible”, “an independent third-party certification scheme” with “external audits to monitor and publicly demonstrate compliance”, or “express, opt-in consent”.

These are worthy, but don’t really alter the power balance between information-vacuuming giants and individuals. That can only be done by giving consumers far more power to monitor how companies are using their data, backed by stringent enforcement that will make it punitively expensive for companies not to comply. The ACCC goes part of the way there by giving consumers a power to erase their information, backed by increased penalties. But consumers should also have the power — backed by strong penalties — to obtain all the personal information held about them by a company, details of every commercial arrangement within which that data has been transferred or sold to another party, how that data has been used and details of the source of all personal data not provided by the consumer themselves.

The ACCC does go much further in a related area. It recommends:

… the government adopt the ALRC’s recommendation to introduce a statutory cause of action for serious invasions of privacy to increase the accountability of businesses for their data practices and give consumers greater control over their personal information.

The case for a statutory right to privacy is so strong as to be a no-brainer. But governments of both stripes have dragged their feet on multiple recommendations for a statutory right to privacy over the last decade. The media hates the idea of such a right, which would give Australians some capacity to fight back against salacious tabloid journalism without any public interest. Indeed, Australia’s legacy media is actively hostile to the entire idea of privacy, having been cheerleaders over the last five years for increased government surveillance — most recently with the government’s encryption backdoor bill, enthusiastically supported by senior journalists.

No wonder both the Financial Review and The Australian editorialised that the ACCC’s push for more digital media regulation should be carefully vetted and confined to their competitors. Google and Facebook are privacy annihilation machines. Legacy media would much prefer to play that role themselves.

Corporate interests are generally the motivation for most political party policy or inaction.

Our rights to privacy should have been defended from digital exploitation at the least, there is no national interest in not protecting citizens privacy from untaxed multinationals.

One of the problems that the population at large has with the new world of online media, is that we’ve brought our old, broadcast-media mindset, where we are just passive consumers of the information that media companies decide they want to feed to us, into a new environment over which we can (if we wish, and if we are prepared to put in the effort) exercise considerable control.

For example, Google isn’t the only search engine. There are others that we can use fairly easily. Nor are we tied to using just one search engine all the time. Mix it up a bit: use a different one every week. If nothing else, this dilutes the attractiveness of a single dominant search engine provider to its advertisers.

It’s not quite so easy with platforms such as Facebook because they have set themselves up specifically as places that we can use as a repository for all of our personal data, but at least we can diversify our functional use over multiple platforms. Don’t use Facebook for news feeds, for instance.

And if you do commit to just a single platform, at least read its privacy policy beforehand so you know what you’re signing away. How many people have read Google’s privacy policy, for example (here: https://policies.google.com/privacy) or Facebook’s (here: https://www.facebook.com/privacy/explanation), I wonder? If we can’t be bothered reading these, then maybe privacy isn’t such a great concern for us?

Either way, for better or worse, some of the onus of how we use the internet lies with us. I’m saying this not as some form of ‘victim blaming’, but because I think it’s important to realise that we don’t have to wait for governments to act. We are empowered already.

“This reflects not merely that this area is the intersection of two of the biggest issues in contemporary capitalism (market dominance and exploitation of private information)…”

It may well be that “market dominance and exploitation of private information” are the two biggest issues in the contemporary communications-media field but within contemporary capitalism I’d say that global warming and energy eclipse any communications matters.

Privacy of information, and all the metadata about sites we visit is now wholly irretrievable. That genie is now well and truly out of the bottle.

Even Google and Facebook couldn’t retrieve and delete any personal information they’ve sold about you. They know not where it’s gone, nor do they care.

The deep root of the problem, which the ACCC can’t get to because it’s basing its thinking around “consumers” is that the transactional nature of consent as expressed in privacy law is broken. It doesn’t matter how simple you make a privacy notice if people don’t read it. People can’t remember what consents they’ve given, and they definitely can’t remember which website they visited last week, so the whole notion they can exercise control is daffy. We don’t expect people to regulate their own medicines, we don’t expect them to test their own cars, and we don’t expect them to investigate their food chain – we assume the government will regulate for the public good to provide a minimum standard of safety. For the problem of data profiling to be solved, the power of data brokers (including the non-media players, like Quantium) will need to be substantially reduced.

If this all sounds horribly lefty, bear in mind that we’re seeing the toxic effects of data mining and targeting having deep impacts on the democratic process. Is Gilets Jaune a grass-roots movement, or does it have a helping hand from Facebook astroturf? There are impacts here that represent a real threat to national security – certainly far more serious threats than the ones we just got encyription legilsation to solve.