On February 16 1983, between 9.10pm and 9.20pm, the Victorian town of Cockatoo was removed from the earth. A fire had been burning lazily on the outskirts of town when 100km/h winds sent it eastward to wash over the community like a wave.

Firefighters were locked out by the wall of fire which periodically exploded when engulfing eucalypts. More than 100 children were led to the local kindergarten and ordered underneath wet towels. A skeleton crew clamoured to the roof with buckets and hoses. An hour later, the kindergarten was one of eight buildings left standing. Across the road, the town hall twirled in a whirlwind of soot.

But by the end of the week, after most houses were replaced with caravans and tents, the community remained. Sixty-five percent of those in town that day decided to rebuild and stay. They’d known the risk when they moved in. And they were willing to chance it again. That number has since dropped down to 5%. Many left town after 2009’s Black Saturday fires. The deadly front was contained 10km away from town which was close enough to bring back bad memories.

One of the more neglected elements of climate change, often forgotten in the face of a rising tide, is the fact that large swaths of the planet currently inhabited will be condemned to destruction through severe drought and heat. This is most often addressed by politicians’ “won’t someone think of the farmers!” rhetoric, but farmers aren’t the only ones on the frontline. Around 10% of Australians live in small towns, and current projections suggest that many of their communities could very well be rendered uninhabitable.

One of these communities is Cockatoo, my hometown, the town reborn from embers.

The Ash Wednesday Bushfire Education Centre, set up in the refurbished kindergarten that hid the children that day, holds dozens of old photographs and news clippings as a testament to those who remained. Bird’s eye shots of people resetting the foundations on charred chunks of land. A young couple with bleached and feathered mullets smiling as they hoist the church sign back into place. Two attendants walk me through the days immediately following, explaining how the place I grew up was resurrected.

“There’s just something about this place. You know, my son hated it here as a kid, he was always complaining that there was nothing to do. When he turned 18, he headed up to Cairns. When he started his own family, they headed down to the Gold Coast. And then they moved back down here. He told me, it’s impossible to raise a family in that place, it’s hard enough living there on your own!”

“There’s not many people left who remember [though]. It was Black Saturday that drove them out. Something about it felt different. People didn’t feel like they could hold up against a fire like that.”

I remember that Saturday; the sky was gold through the smoke. I shouldn’t have been outside at that point, but had decided to take the “too late to leave” warning for Cockatoo literally. I stood on the nature strip and took in the horrible glow. 70kms away Marysville smouldered.

I ask if people talk about climate change, if they feel a rising threat. The other attendant speaks up with a stern voice.

“People in Cockatoo have noticed the changes in weather. I even set up some equipment behind the house, thought to measure the rain, and it’s clear we’re getting less. Not only that, but now it’s coming down in massive bursts when it does come. That means we’re going to have a much longer fire season and far less time to prepare through burn-offs.”

“I love this place. I just hope it’s always here for everyone to enjoy.”

The conditions leading up to Ash Wednesday were like biblical plagues. The town was partway through the heaviest drought on record and facing pressure systems with 100 km/h winds that could change direction in an instant. A week before the fire came, we had the Melbourne dust storm — an ominous warning that blotted out the sun.

Black Saturday came with similar conditions, a dry winter with freak air patterns that resulted in searing blasts of hot air into an environment already edging on ignition point. But these were no longer freak conditions for February. The climate had changed since 1983. Even without the technical knowledge, locals can tell you it feels hotter, that this drought feels worse than last time, that the windows have started to rattle in their frames. People stayed after Ash Wednesday because they thought it was the worst of the worst. They left because Black Saturday showed that this was not the case.

Just like the volunteers at the AWBEC, I hope the community of sunny people at the foot of Mt Dandenong remain. But with each rainless winter month, I look to the air and find it’s tinted a little more gold.

The Inquiry into Ash Wednesday revealed that forestry used only ‘dry firefighting’ – burning backburns onto fires. They still do and the backburns often greatly increase the size of fires and the length of time they burn for – but rarely kill or injure people as they are deliberately lit – and deemed ‘a success’. There was little analysis of these fires. I was burned out at Mount Macedon same day/night. A court case determined these fires were started by a powerline against trees – but the settlement were more a lawyers feast. It was with extreme irony that powerlines were the cause of 6 of the 13 Black Saturday fires and the recommendation for underground powerlines was dismissed. Power was privatised and maintenance again neglected Like in a fire place, you open the flue and it burns harder. In semi rural towns dry European and other introduced grasses fuse fire rapidly along roads, across paddocks and up driveways. Not all trees burn the same – some even stop fires – especially wattles even gumtrees with people at Stathewan sheltering behind large gum trunks. Even highly flammable cypress hedges around properties on ash Wednesday stopped fire. Cypress fire breaks in East Gippsland have worked in similar ways. In high wind and extreme heat blocking the wind is the most effective.Fire breaks can be fire fuses depending on which way the wind blows – see recent Tathra NSW fires in heavily fuel reduced bush. During the royal commission researchers used data regarding people who lived staying in their homes compared to people who died outside them – less than a dozen people overall. As they were not there they did not see the hundreds that fled down the mountain and survived. They did not talk to people who stayed in their homes as long as possible, got out onto the lee side and, with blankets around them, camped on burned grass until the fire past. If they followed lat recommendations which as still current they would have died.

An acquaintance who lived near Pakenham Upper stayed with the house during the 1983 fires. He and others with him saved the house, however, in the hours that passed after the fire-front went through, he saw houses that had initially survived catch alight and burn to the ground.

The same thing happened with the 2013 Blue Mountains fires – the Coroner determined these fires were started by a powerline against trees – but the settlement was consumed by the lawyers feast.

Modern day Jarndyce & Jarndyce. I’m a fan of Dick the Butcher from Henry VI.

As CO2 increases in warmer growing seasons, growth of the (C4 photosynthetic) grasses at the expense of (C3) trees means that there will be more fuel on the forest floor during the drying season. Forest fires will increase until the biomass of the world’s forests decreases to a new equilibrium with CO2. Let no one pretend that we can store excess carbon in the surviving forests.

Would,in your opinion(which I don’t always agree with but find worthwhile nonetheless ) protection/preservation of existing forests and worldwide planting of a shitload of trees be able to change the scenario as you’ve described it ?

Hi MacTez. Yes, we need to protect the forests because the world needs forests. And it would be good to see trees planted alongside every roadway. But we could not possibly grow enough extra trees to take about one thousand gigatons of the recent extra CO2 out of the atmosphere and keep it out of the atmosphere and ocean for thousands of years. Each gigaton of CO2 approximates an impossible cubic kilometre of wood, yet 40 more gigatons go into the atmosphere every year. Unfortunately, the arithmetic is against us. We just gotta stop emitting.

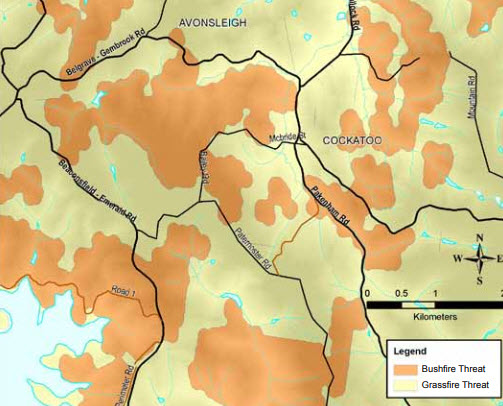

I believe authorities have maps that can be used to predict the likely direction of bushfires similar to flood maps.

It may now be time to be realistic about where we continue to allow human habitation

It’s a debate that cannot be swept aside as the fire seasons are starting earlier and become increasingly dangerous. To hear the warnings for people that they were too late to evacuate sent a chill uo my spine.

There is always a moment in time when choice exists; act now or fail. Climate has rung a bell. Science concurs. Who prevaricates, who fails? To act. Call out leadership in denial. Acknowledges communal endeavour is first bulwark available. There is always a moment in time when choice exists. Act now, or fail. Human adaptability is energised by a single decision and empowered when embraced by community. Leadership offers focus but cannot progress without unity. Motivation supplies the means.

Climate Change means sons, daughters, grandchildren at risk.

You are right graybul. Liz Hanna, a climate change and health specialist has a frightening piece today in John Menadue’s blog Pearls and Irritations about what we are facing with extreme heat. Sorry can’t do the link on my device but it’s worth a read.

Appreciate heads up Vasco. Just followed up on your suggestion to visit J M’s excellent Pearls and Irritations. Liz Hanna’s measured post fits. ie “. . . always a moment in time when choice exists . . ” Really, seriously scary . . . LNP TIME IS UP! A change of heart won’t cut it. ALP MUST FULLY COMMIT. MOVE TO FRONT FOOT OR TIMES UP! We need leadership’s full attention right now.

Even in Sydney’s easter suburbs beach climes the last two summers have been ridiculous. I could count on 3 or 4 nights per summer that would be humid and uncomfortable. Now it’s half the summer or more. There are other examples of introduced flora causing ongoing issues, none more obvious than dune care at beaches with introduced grasses.

Everything we touch we f #@%k up.