At the NSW Liberals’ election launch yesterday, Prime Minister Scott Morrison — who hails from Cronulla (well, Bronte, but anyway) and who used to be the party’s state director — sat silent while Gladys Berejiklian tried to revive her campaign. Polling in the Sunday papers showed her government trailing 51-49. That’s not enough for NSW Labor to win, but it’s utterly shocking given this should be an unloseable campaign for the Liberals.

It’s just as well that Morrison kept quiet (in contrast to Bill Shorten, who fired up the Labor faithful at Michael Daley’s launch across town). It was only a few days since the Prime Minister had smirkingly celebrated International Women’s Day by declaring women shouldn’t get ahead at the expense of men. Not a good look for a female premier.

But Morrison haunts Berejiklian in a way that can’t be hidden through any amount of stagecraft. The removal of Malcolm Turnbull last August was a savage blow to the NSW Liberals, and Morrison has been a dead weight on them ever since. How do we know? There’s hard evidence.

We know that last week’s December quarter national accounts showed economic growth slowing from a total 1.9% in the first two quarters to a total of 0.5% in the September and December quarters. But there was also a sharp slowdown in consumer spending in 2018. And it starts in August — the month Morrison replaced Turnbull.

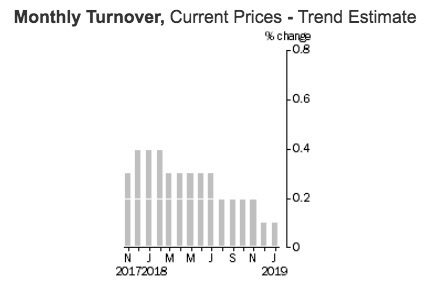

Last week’s retail sales data from the ABS shows sales rose 0.1% in January (seasonally adjusted) from December and 2.7% over the year. But that obscures the dramatic slowdown during 2018: the annualised rate of growth of 3.4% for the February-July period slumped to an annualised rate of just 2% for the period from August to January this year. The step down in August is particularly noticeable in the trend sales figures.

But the slide was worse in NSW, which accounts for 28% of national retail sales. Retail sales in NSW slid from an annual rate of growth 5% in the six months to July 2018 to an annual 0.6% in the six months to January. In fact, the seasonally adjusted value of sales in January in NSW ($8.68 billion) was lower than in July of last year ($8.72 billion). In other states like Victoria and Western Australia, retail sales slowed over the same period but January sales volumes were still higher than the previous July.

It’s true that house prices have fallen faster in Sydney than elsewhere — though prices in Victoria have fallen by nearly as much, without the same fall in retail spending. But unemployment is also much lower in NSW than anywhere else — at 3.9%, currently. And none of that explains why August marks the start of flat or declining retail sales in our biggest state. In trend terms, the last time there was a rise in retail spending in NSW was in July before Turnbull was ousted.

The slowing of the national economy in the second half of 2018 can’t all be pinned on Morrison, of course. But NSW voters evidently were underwhelmed with the removal of Turnbull in August. Very likely Peter Dutton would have made the situation dramatically worse. But Scott Morrison has failed to address the deep uncertainty created by the ouster of his predecessor, despite buoyant economic times in his home state.

Perhaps that’s because NSW voters know him better than voters elsewhere. Either way, he’s bad news for Gladys Berejiklian and a competent government facing a remarkable defeat.

Competent? My arse.

Hear, hear. TheNSW Coalition government only looks good because it hasn’t quite yet pissed up against a wall, all the money it got from the fire sale of just about every national asset that it could.

Thank you applet. Saved me the trouble.

Bernard keeps running this line and – as far as I can tell – hasn’t had a single Crikey reader agree with him. But he keeps trying.

It’s very trying.

Look, I hate Morrison and all, but to be persuaded that this isn’t just coincidental I’d want to see evidence of past consumer spending trend changes coinciding with major political events like this.

No difficulty tying the fall in consumer spending to the general malaise of the Coalition government and stagnating or falling real wages, coupled with the fall in house prices. There’s a logical connection there. Making the specific event into Malcolm’s fall seems a bit OTT. I’m sure Malcolm loves that narrative but as it stands it’s just a narrative, and personally I think that it would have happened just as much with Turnbull still at the helm.

Same time as house prices started to fall Arky. Much more correlation with that. ScoMo is just road kill along the way.

Also speaks to the stupidity of Sydneysiders thinking that the price of their house has any meaningful impact on spending. Whether you’ve worked it out or not, if you’re spending more because you think the price of your house has anything to do with day to day living, you really haven’t progressed beyond year 7 maths.

Not that this is peculiar to Sydney, just suggests they are more susceptible than most.

The WA Liberal government was criticised for wasting money on a major sports stadium in a state that didn’t have one. Pulling down two quite good stadiums to build two new ones doesn’t suggest a competent government. Perth people visiting Sydney see many signs of decay and neglect: bad roads, inadequate public transport just to name a couple. Competent? Not that you’d notice.

Delivery or non-delivery of infrastructure projects is super critical to the rise and fall of state governments now.

Look at Victoria. The Brumby government ultimately paid the price for failing to deliver transport improvements and the botched and highly expensive MYKI rollout, with swings against it concentrated down the train lines. Ted Bailieu, under the perception even from Liberal voters that he was a do-nothing Premier, lost the leadership without even making it full term, leading to Napthine’s unholy rush to sign the contracts for East West Link (which didn’t save him), while Dan Andrews saw a landslide – particularly along the train lines in the south and east – despite 4 years of negative stories about the CFA, african gangs, red shirt rorts etc etc- because he started and delivered infrastructure projects on schedule which actually helped people. I told the story at the time of driving in Melbourne the day before election day and seeing a billboard of Matthew Guy with a slogan about ending traffic chaos… in area where the traffic was better than it used to be because a level crossing had been removed in time for the election.

Where I’m going with this is that as I read in the press about the long delayed, highly inconveniencing light rail and road projects in Sydney which are not complete before the election, coming from a government which has been in a power for 8 years and can’t blame the Opposition for it, I can smell the punters’ rage from here- and this government is talking about spending hundreds of millions on stadiums next. Geez.

Your olfactory senses are picking up the same breeze I’m sniffing Arky.

Seems strange to think the NSW economy would be dependent on Turnbull’s fortunes – so in awe of his “achievements(?)” in government – I wouldn’t.

How about sales from Sydney’s George St to way out west, along the Darling?

I reckon it wouldn’t have mattered who was steering the Limited News Party Coal-ition lubed bobsleigh and whether they ejected them – with a dead-weight anchor like the BCA it was always going to be a pile too far.

dont believe the polls, glady will lose the election with a little help from scummo but largely due to the conservative brand it stinks likeweek old road kill on a summers day, l