With a federal election less than three months away, attention is turning to what a likely federal Labor government might look like.

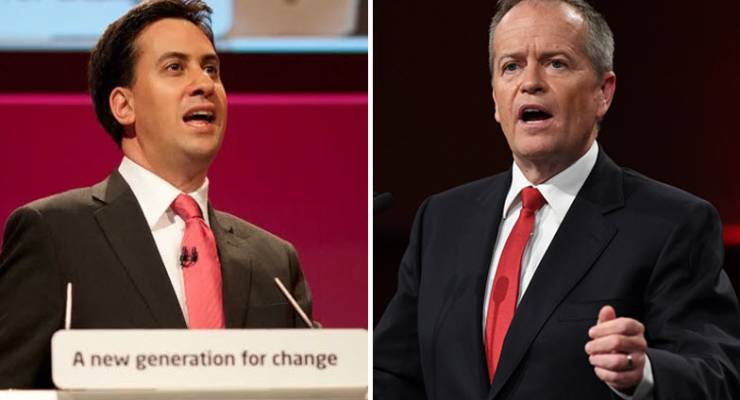

While Shorten has attempted to draw parallels to Bob Hawke’s style of leadership, the best comparison may instead be with a UK Labour government that never was: the unsuccessful 2015 campaign and platform of Ed Miliband in 2015.

Labor’s offer in 2019 is an antipodean version of Milibandism, conceived by industrial labourism instead of a soft left Fabianism that provided the philosophical Labour underpinnings in the United Kingdom.

What do I mean by Milibandism? Broadly, it entails a critique of the financialised form of capitalism and concerns about growing inequality. The cost-of-living squeeze on the middle-class is a concern, as is the protection of public services from privatisation. There is a greater focus on tax avoidance and specific targeting of the wealthy to reduce taxes for the lower paid. There is also a reliance on an agenda of predistribution to do the heavy lifting through reforming markets, encouraging wage increases and ending insecure work practices.

There remains a concern about debt and deficit, hemmed-in by a mindset of working out what social democrats can do when there is no money. And, hovering over it all, is the spectre of a compromise between the “Blue Labour” and remnants of the now defunct Blairism.

Federal Labor’s policies today all echo the same themes of this manifesto: reducing tax concessions to fund tax cuts and public services; a focus on cost of living; calling for a “living wage”; cracking down on labour hire; and fiscal rules to reduce debt and run surpluses of at least 1% of GDP.

But there are other parallels beyond policy. Like Miliband, Shorten was elected to leadership with underwhelming support. While also not being publicly popular, he too has challenged what policies are seen to be politically acceptable. Unlike Miliband however, Shorten’s skills in manoeuvring through internal Labor politics with a cross-factional coalition of union support leave him in a far stronger position to negotiate compromises.

While the ALP’s latest offer has a far more egalitarian impulse than similar platforms in the recent past, it is not one that has captured the public imagination. Any federal Labor victory will primarily be due to people voting against the Morrison government. Political disillusionment is strong and there is little public excitement for the prospect of Labor winning the election.

How this antipodean Milibandism will operate to tackle big issues will be harder to see. There have been signals of a shift away from Labor’s commitment to neoliberalism, but major challenges such as climate change cannot be addressed with tweaks or market regulation. Properly responding to climate change within a decade will cost significant amounts of money and it is unclear how Labor will overcome these challenges and cut through the disillusionment and distrust that has corroded our institutions at the same time.

Regardless, with Australian Labor likely to win the upcoming federal election, a Shorten government will be cited globally as a model of moderate social democratic “success” to counterpose against Corbynism (as I have previously argued). A recent article by Adrian Pabst in the New Statesman — that incorrectly characterises Australian Labor as radical and patriotic — shows this is already happening.

Australia is already gaining a global reputation as a kind of “Scandinavia for moderates” in an era of populism. How a Shorten government acts is unlikely to change that.

Osmond Chiu is the Secretary of the NSW Fabians. He tweets at @redrabbleroz.

“What do I mean by Milibandism? Broadly, it entails a critique of the financialised form of capitalism and concerns about growing inequality. The cost-of-living squeeze on the middle-class is a concern, as is the protection of public services from privatisation. There is a greater focus on tax avoidance and specific targeting of the wealthy to reduce taxes for the lower paid. There is also a reliance on an agenda of predistribution to do the heavy lifting through reforming markets, encouraging wage increases and ending insecure work practices. ”

Apparently Crikey is paying by the buzzword now.

Incidentally, the idea that that quite general set of ideas is so associated with Ed Milliband as to name it after him, I just have no words.

Wow. I thought the article might have been about about assuming Labor’s going to win the next election but they actually get trounced at the post for boring us to death.

Though after reading it, I think it spells out a reason for it to be a one term Labor govt for boring us to death.

What is “predistribution”?

And surely the “cost-of-living squeeze” (if it is not just a re-branding of wage stagnation) has more impact on the working class than the middle class?

The Labor government is not even here yet…but we already have the ‘left’ knocking what it might do/achieve.

Words fail me!!

So many “…ism”s that my head nearly exploded! Chiu needs to explain things very much more clearly if he expects people to

a) understand what he’s saying, and

b) agree with him.

Oh, and the Fabians are soo last century!