In 2010 a chunk of hail landed in the town of Vivian, South Dakota that re-wrote the record books. One of Vivian’s 130 residents grabbed it and put it in their freezer. Even after some melting (partly due to being shown off repeatedly to the town’s other 129 residents) the hailstone measured 20cm across and weighed 870 grams when it was officially recorded — the biggest ever seen.

Stories like this make toes curl in the insurance industry. Hailstones larger than golf balls do serious damage. Car windows get smashed. Crops are flattened, and solar panels get turned to shards. All of which can result in major payouts by insurers.

Insurers hate hail. They are very sensitive to changes in the frequency and intensity of hailstorms. But hailstorms are increasing in frequency in Europe, according to research supported by Munich Re, a major reinsurer (an insurance company that insures the risks of other insurance companies). Similar increases have been observed in North America.

This is understood to be most likely due to climate change. Climate scientists theorise that higher levels of humidity related to higher global temperatures are causing more frequent hailstorms.

This is bad news for companies that pay out when disaster strikes. And all this is without even mentioning the fires, floods, droughts, hurricanes and rising sea levels also exacerbated by climate change.

The costs

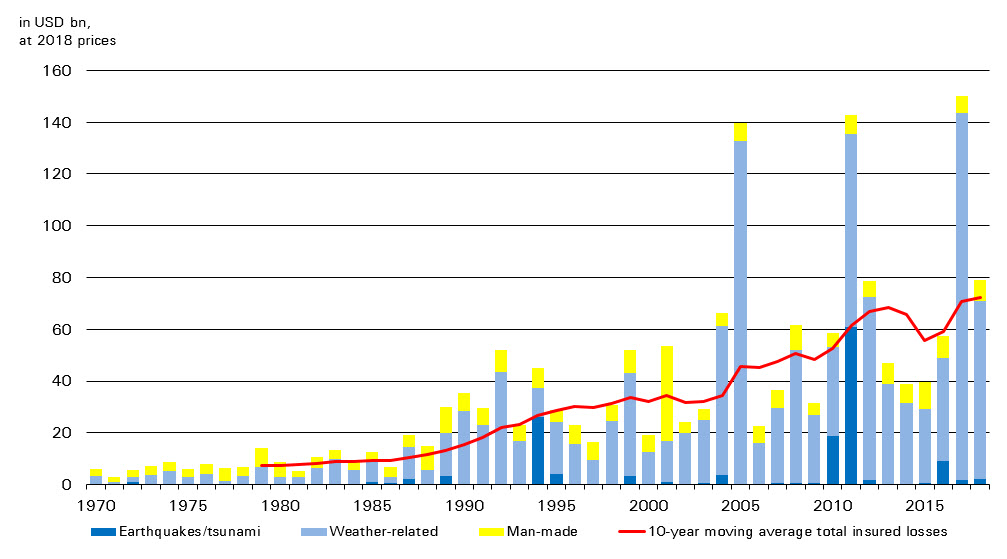

Insurers are already experiencing a large increase in their payouts for losses — especially those related to weather events.

The overall uptrend in insured losses is clear and a huge proportion of those losses is now weather related.

Australia, meanwhile, is not immune. It could see a lot more extreme weather and much higher premiums, according to the Insurance Council of Australia.

“Insurers will continue to offer insurance, but this will be risk-rated to reflect the exposure to extreme weather,” says Insurance Council of Australia general manager of communications Campbell Fuller. “Many parts of Australia may see sharp rises in premiums in coming decades.”

The insurance industry is concerned about climate change affecting areas that already struggle with extreme weather, Fuller said, particularly north Queensland.

Insurers are at the forefront of global risk trends. In contrast to certain other corporate entities, they don’t downplay the risks of climate change. AXA CEO Thomas Buberl said in 2017 that rising temperatures could impose such an unpredictable and enormous cost that they would represent an existential threat to the insurance industry.

“A 4 degree-plus world is not insurable,” Mr Buberl said.

The Australian Actuaries Association has even built a climate index to track extreme weather conditions relative to a three-year baseline.

The reaction

Change is coming to the insurance industry as part of these global initiatives. Premiums are not necessarily being adjusted yet — insurers can vary prices year by year in many cases and will put off price hikes until strictly necessary — but the industry is being forced to calculate and report on its exposures to climate change.

Understanding and reporting climate change risks is a vital step to strengthening the case for avoiding them. Several global frameworks have recently been developed to help financial entities do just that. One example is the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, who created guidelines to help financial entities make useful standardised disclosures on exposures to climate change.

Australia’s major insurers — IAG, Suncorp, Allianz and QBE — now all have Climate Change Action Plans. IAG — Australia and New Zealand’s largest general insurer, and behind brands such as NRMA Insurance, CGU and others — signed up in 2018 as one of 16 companies joining a pilot group developing principles for climate change risk assessment under the UN’s Principles for Sustainable Insurance.

The revenues

In terms of insured risks, where losses loom large, insurers are forward-thinking. But in terms of who they will accept as clients — where revenues can be made — the record is more mixed. QBE in particular provides a lot of insurance to coal companies and has won much bad press for doing so.

The choice to underwrite coal is a calculated one — QBE believes it is unlikely to have to pay out for anyone suing the coal companies. QBE’s annual report acknowledges that energy companies could be sued for damages caused by climate change and that regulators have already sued large energy companies in the USA. It observes, however, that such legal actions have so far failed.

“We do not currently regard liability risk to be significant but continue to closely monitor developments in this area,” the report says.

But theirs is not the only view on liability. A legal opinion published by Minter Ellision in 2016 argued climate change risks were foreseeable and relevant to a director’s duty of care under Australia’s Corporations Act. Australia’s insurance industry regulator APRA has also declared climate change risks “foreseeable, material and actionable now”.

One thing that reporting on climate change risks will do is reduce the ability of insurers to deny they understood the dangers. When everyone understands what the future could bring, standards for liability may shift.

Just like enormous hailstones, what was previously unprecedented is suddenly becoming a reality — don’t expect legal terms to be exempt.

This piece is part of our dedicated climate change series, Slow Burn. Read the rest here.

Does the insurance industry have a responsibility to prepare for climate change? Let us know at boss@crikey.com.au.

Insurance is one example of commercial capitalist mechanisms being incapable of handling the increased risks posed through climate change efficiently, or at all.

There is much expression of deeply touching concern about “moral hazard” of offering crop insurance to farmers. This apparent anxiety to restrain their apparently extreme desire to ignore all the other issues relating to their farm would even be believable if such high-minded and noble principles were ever applied to the banksters of Wall Street – people who’ve never done an honest day’s work in their lives and most certainly don’t intend to break that record of achievement.

Banksters indifference to risk on the basis that the taxpayers would accept liability was demonstrated on an enormously greater scale following the collapse of Lehmann Brothers – a comparison not mentioned by either ABARES or NRAS – two organisations that investigated crop insurance.

Naturally State Agriculture Ministerial nonentity and WA National ideologue Terry Redman in 2014 opposed an insurance scheme underwritten by government. No doubt why in 2010 two WAFarmers zone meetings passed votes of no confidence in him, and voted for the Government to introduce or support a multi-peril crop insurance scheme or what is now being dubbed a “risk management crop scheme”.

Australia’s first multiple peril crop insurance product was offered in 1974-75 by Wesfarmers and Western Underwriters. The product suffered from a lack of appropriate data, adverse selection and poor take-up by farmers and was consequently discontinued.

Only universal, compulsory government schemes will be equitable – workable – in the 1.6º+C world that we now have.

Insurance was probably the first bastard offspring of commercialism – originating in Venice and based on the minute arbitrage possible using the newfangled spyglasses atop towers to see a ship returning from a successful commercial venture.

(They knew they were successful else they’d not dare return.)

It would be nice balance if it were the first to die.