The claim

The Coalition has used the 2019 budget to match Labor’s promise to end the Medicare rebate freeze should it win the election.

On the day Labor announced the promise, Senator Kristina Keneally tweeted: “Under [Scott Morrison] and the Liberals, out-of-pocket costs to visit a GP are up 25 per cent and out-of-pocket costs to visit a specialist are up 40 per cent — because of the Liberals’ & Nationals’ Medicare freeze.”

So, has the cost of seeing GPs and specialists gone up, and is the rebate freeze to blame?

RMIT ABC Fact Check takes a look.

The verdict

Keneally’s figures broadly check out, but there’s more to the story when it comes to increased out-of-pocket costs.

For a start, the initial 10 months of the rebate freeze was imposed on Labor’s watch.

At any rate, experts told Fact Check the increase could not be solely attributed to the freeze, which has now been lifted for GP consultations.

Rather, they also blamed increased out-of-pocket patient costs on the rising cost of running a GP practice and the way in which general practice medicine was being funded overall.

How does Medicare work in relation to GP and specialist visits?

The Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) outlines medical services offered to individuals that are funded either partly or in full by the Australian government as part of Medicare.

Items listed on the MBS, including GP visits, are subsidised on a fee-for-service basis.

According to the Parliamentary Library’s quick guide to Medicare, the government sets a mandated “schedule fee” for each item, and refunds different percentages of this fee depending on the circumstances in which the service is provided.

“A service provided in hospital attracts a benefit equal to 75 per cent of the schedule fee; a service provided out of hospital generally attracts a benefit of 85 per cent.

“In the case of non-referred attendances (those provided by a general practitioner (GP)), the benefit is set at 100 per cent of the schedule fee,” the guide says.

The current schedule fee for a GP visit is $37.60. The schedule fees for specialist attendances range from just over $32 to more than $166.

When a GP accepts the schedule fee as full payment for the service, the patient pays nothing. This is known as “bulk-billing”.

However, GPs may charge more than the schedule fee, with the difference being met by the patient from their own pocket.

This is referred to as an “out-of-pocket” cost.

What is the Medicare rebate freeze?

Schedule fees were previously indexed annually in November using the Department of Finance’s wage cost index.

But in the 2013/14 budget, the then-Labor government announced that these Medicare rebates would instead be indexed at the beginning of each financial year.

This meant the rebate was effectively “frozen” between November 2012 and July 2014, predicted to deliver savings of $664.4 million over four years.

The incoming Coalition government introduced a further freeze in its 2014/15 Budget, pausing rebates at the July 2014 level for two years. GP schedule fees were exempt from this pause.

Then, in December 2014, the Coalition announced all MBS schedule fees, including those for GP visits, would be held at 2014 levels until July 2018. The 2016/17 budget extended this through to 2020.

In the 2017/18 Budget however, the government backtracked partially, subjecting GP services to indexation as of July 2018.

In March, Labor promised to end the MBS rebate freeze for all other services within 50 days of forming government, should it win the May election.

This would mean all schedule fees would be indexed annually from July 1, 2019.

The Morrison government matched Labor’s promise in the 2019-2020 budget.

Have out-of-pocket costs increased?

In an email, a spokeswoman for Kristina Keneally told Fact Check the senator had been referring to NSW figures in her tweet, but that national figures on out-of-pocket costs were consistent with the state picture.

The Department of Health publishes quarterly and annual medicare statistics, which include data on out-of-pocket costs.

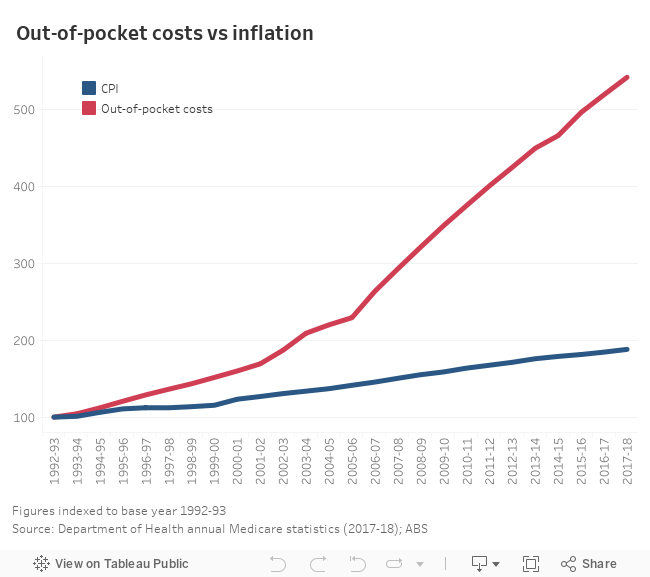

The latest annual figures, published in December 2018, show out-of-pocket costs for visits to both GPs and specialists have risen steadily since the early 1990s, where the data series begins.

From 2012-13 (the last full year when Labor was in government) to 2017/18, out-of-pocket costs to see a GP increased by 28 per cent. The cost for patients to see a specialist rose by 40 per cent over the same period.

Putting increases in out-of-pocket costs in context

In her email, the spokeswoman for Keneally pointed to a pre-budget submission published by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) in which it suggested that, since 2005-06, costs for patients had risen by 140%.

It singled out Medicare rebates as a key reason for the rising cost for patients, though the freeze was only part of the problem; the college also took issue with how indexation was applied.

“The patient rebate has not kept pace with inflation,” its submission reads.

While this was “largely due to the Medicare rebate freeze resulting in a lack of indexation”, it was also because the government used the wage price index as its yardstick for indexation as opposed to consumer price index.

A ‘complex issue’

Fact Check asked experts whether Keneally could fairly attribute the rise in out-of-pocket costs solely to the Medicare rebate freeze.

All experts said a number of factors, including the freeze, would have contributed to the higher patient costs.

Margaret Faux, a lawyer specialising in Medicare and health insurance law, told Fact Check the increase in out-of-pocket costs was a “complex issue”.

Ms Faux, who is completing a PhD on Medicare claiming and compliance, pointed to high salaries, expensive equipment and large insurance premiums as structural problems within medicine that could be pushing up prices.

“Yes, [the rebate freeze] is having an impact, definitely, but if it is lifted it still isn’t going to be enough to enable GPs and specialists to run a bulk-billing practice, and practice medicine in the way they would like to practice it,” she said.

“They are still rewarded for six-minute medicine.”

Helen Dickinson, professor of public service research at the University of New South Wales, agreed that rising out-of-pocket costs was a complicated issue reflecting more than just the rebate freeze.

“In 2018, for example, the freeze on GP consults was lifted and was re-indexed by 55 cents, so it’s not a massive amount,” she said.

“It’s probably true to say that the freeze has made the issue worse for some practitioners, but the main thing the RACGP and others are saying is that, actually, the problem is how funding is organised and distributed.”

The RACGP has taken issue with the funding of general practice, stating in its pre-budget submission: “Despite general practice being the most accessed form of healthcare, it represents only 7.4 per cent of total government (including federal and state/territory) health expenditure.

“Successive funding cuts to general practice, including Medicare … has had a devastating impact on health service delivery.”

Other ways of responding to the freeze

Associate Professor Kees Van Gool, of the University of Technology Sydney, said there were a number of ways GP practices could react to the rebate freeze other than by charging patients higher out-of-pocket costs.

“They could try and reduce their practice costs, they could merge with other practices, or they could seek to increase the volume of services they provide.”

This was echoed by the RACGP in its submission.

“Many GPs have forgone income and absorbed the rising cost of providing care in efforts to ensure services remain accessible and affordable to patients.”

Principal researcher: Ellen McCutchan

Sources

Kristina Keneally, Twitter, 25 March, 2019

Department of Human Services, About Medicare, 19 March, 2019

Federal budgets: 2013-2014, 2014-2015, 2017-2018, 2019-2020

Mid-year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, 2014-2015

Department of Health, Medicare Statistics, financial year 2017-18

This article was originally published at ABC.net.au

“Many GPs have forgone income and absorbed the rising cost of providing care in efforts to ensure services remain accessible and affordable to patients.”

That’s lovely……until you have to put food on the table & a roof to keep over your head. Seems like yet another way in which the alleged “Budget Surplus” is built on screwing over the Australian people.

The GP practice I go to does not bulk bill me or my mother, who is a pensioner.

In my infrequent visits I have found that the price goes up just about every time.

As a diabetic I need to go a couple of times a year to get referrals or scripts. Sometimes for scripts they will bulk bill, other times not.

The out of pocket cost is nearly as much for the GP as it is for the specialist.

I believe there should be a cap on out of pocket expenses. Otherwise GPs will become too expensive to visit.

It seems Crikey are letting Labor off the hook.

Did Crikey write this:

“For a start, the initial 10 months of the rebate freeze was imposed on Labor’s watch.”

And that is the crux as Kristina is comparing Liberal to Labor.

She is trying to paint Labor into a good light.

That can not be done

Liberals and Labor are much the same as each other, two peas in a pod.

Both bad news, different sides of the same coin.

The Conservatives absolutely detest Medicare, they fought against its introduction and will do anything in their power to undermine it.

The only way to curb excessive ‘out-of-pocket’ doctor’s costs, is to completely overhaul the way Medicare Provider Numbers are issued to all doctors. At the moment, they have the say about where they set up in practice…when it should be the government, on behalf of the taxpayers who pay for Medicare, demanding MPNs only be issued where services are required.

I suspect the doctor/patient ratios are very different in the suburbs compared to those in rural/remote areas. Doctors can still set up practice in the city if they wish, but should NOT automatically receive a MPN in areas which are already over-serviced…because this leads to fewer patients per doctor and larger out of pocket fees to maintain expected income.

Where public money is involved, taxpayers have a right to expect equality of access to doctors and healthcare generally…no matter where they live.