In spite of everything, the Coalition appears to be entering the campaign for the May 18 election in a spirit that can at least be called hopeful, if not quite optimistic.

Their reading of the situation is mirrored in the Labor camp, which is taking a conservative view — for a party that retains a clear edge in the polls — of what seats to target.

The Coalition ended the term on 74 seats out of 150, two down on the 2016 election thanks to the Wentworth byelection and the resignation of Chisholm MP Julia Banks.

A further incremental setback looms with the growth in the ACT’s seat entitlement from two seats to three, a free kick for Labor that will increase the total number of seats to 151.

Redistribution in Victoria also gives Labor a headstart in the Liberal-held seat of Dunkley, and eliminates the Liberal margin in their already precarious seat of Corangamite.

To get into a position where it is even able to cling to minority government, the Coalition will need to hack a path through seats currently held by Labor.

That seemed a distant prospect for most of the past term, but in New South Wales at least, the Liberals have ratcheted up their expectations after their surprisingly clear win in the recent state election.

Their biggest show is the mystically significant seat of Lindsay on Sydney’s western fringe, which Labor strategists famously structured their entire campaign around in 2010.

A white working-class electorate of tradesmen and machinery operators, Lindsay was gained by Labor in 2016 off a swing of 4% — the first time it had been won by the losing party at an election since it was created in 1984.

Lindsay is ground zero for Liberal campaigns on border control and the alleged impact of Labor’s environment policies on power bills and heavy vehicles. Voters there are better attuned to the purposefully suburban image presented by Scott Morrison than to the urbane and managerial Malcolm Turnbull.

Another opportunity for the Coalition to pump its deflated tyres is the Townsville-based seat of Herbert, which Labor won in 2016 for the first time since Paul Keating was prime minister.

The key issue then was the severe and ongoing economic hangover from the end of the mining boom, which the government hopes it has turned to its favour with its approvals for the nearby Adani coal mine project.

With the rural Victorian seat of Indi expected to revert to type with the retirement of independent Cathy McGowan, and a growing conviction that Kerryn Phelps’s byelection win in Wentworth will prove to have been a one-off, Liberals who have spent the better part of six months engulfed in despair are now daring to imagine what victory might look like.

In the opposite corner, Labor goes into the election with 69 seats carried over from the last parliament, and can be certain of gaining the new seats of Fraser in Victoria and Bean in the ACT, and very confident about the redrawn Dunkley and Corangamite.

At least for starters, Labor’s strategy is to build a firewall out of the clear advantage it enjoys in Victoria, targeting Chisholm, the only seat they lost in 2016, and the eastern Melbourne seats of Deakin and La Trobe, held by Duttonite Liberals Michael Sukkar and Jason Wood.

Labor also expects to gain two seats off its still pitifully low base in Western Australia, where its brand was rejuvenated by the landslide state election win in March 2017.

With that accomplished, it need only tread water in New South Wales and Queensland — and for all the bullish Liberal talk, that seems eminently achievable as things stand at present.

The cosmopolitan inner-Sydney marginals of Reid and Banks present the Liberals with the same vulnerabilities that beset them in Victoria, and the surge of support they believe they have picked up across the state may yet prove to have been a short-term artefact of voter confusion over the state election.

Queensland must also be considered a game of two halves, with the threat to Labor in Herbert balanced by opportunities in Brisbane, up to and including Peter Dutton’s seat of Dickson.

It is with good reason that Labor starts the campaign as short-priced favourites with the bookies.

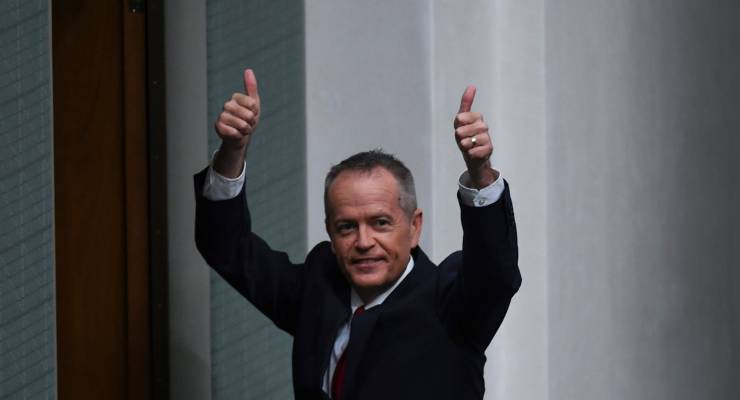

But with the experience of Labor’s disastrous state election campaign in New South Wales fresh in the mind, and over a month’s worth of campaign obstacles ahead of him, Bill Shorten can take nothing for granted.

An observation for those running parallels between the NSW State election and the Federal election.

If I remember correctly, the NSW State polls had been pretty much even stevens for the 12 months preceding the election . It would appear to me that NSW Labor’s problem is that its vote is locked up in safe seats, so the 49% TPP didn’t translate into marginal seat gains.

The Federal polling has been consistently pro-Labor for several years, except for a brief time when MT narrowed the gap. And the Federal ALP does not need a significant swing just to gain marginal seats from the Coalition.

Is there any actual evidence to suggest Wentworth or Indi will go back to Coalition, or just the Libs deciding that they will?

Given the probability of a Labor win, I would have thought that self-interest first see those conservative leaning electorates vote independent again. More chance of getting stuff from a government if they need to convince your MP to vote for them on each bill.

I’m much less convinced than the media that the NSW state election holds anything for the Libs – maybe some additional inspiration for their dirt unit, but that’s about it. Morrison can’t point to any projects underway, and Shorten is unlikely to be revealed to have made racist comments.

Wentworth? Well, it was pretty close in the byelection and doesn’t need many “protest voters” reverting to the Liberals to swing back, and that byelection campaign was a shocker for them. Phelps hasn’t had enough time to use the advantage of being a local member to really sandbag the seat full of people who owe a favour to the local MP. So conventional wisdom is it reverts.

Indi, well, it is practically unheard of for independent MPs to successfully succeed other independent MPs in the same seat and by default the seat is safe Coalition territory.

Arky – So it’s running on the same conventional wisdom that said an independent wouldn’t get up/last in Indi, and that the Libs would always hold Wentworth?

I’m probably wrong, but I don’t find either of those convincing without poll numbers, despite seeing these ideas repeated unchallenged across the papers.

Cathy McGowan has a pretty good election machine that was being hailed as game changing not too long ago, and her being replaced was always in the conversation, and Kerryn Phelps gave a pretty good return on her vote – with only a couple of days as sitting member she got changes to the offshore detention rules and exposed the government on the issue.

Other issues will influence people’s vote, I just can’t get my head around why if you voted for an independent last time, you’d decide to go with ScoMo this time.

I don’t think either of those things was conventional wisdom. To the contrary, actually. All rural seats, especially with a local member as unpopular as Sophie Mirabella was, are vulnerable to a local independent, we’ve seen it again and again and again. And the conventional wisdom was absolutely that Wentworth was ripe for the right independent to take it due to the local anger over Malcolm Turnbull being rolled.

Voices for Indi gives McGowan’s successor a better shot than some independents replacing independents, it’s true.

Whether Wentworth voters are that impressed at Kerryn Phelps’ work with the medevac bill is unknown to me.

I was relieved when the liberals won NSW . It showed that the voters clearly distinguished between state and federal issues. Without joining BK’s hymns of praise, it’s clear that the Berejiklian government is everything the Morrison government isn’t: reasonably competent (despite some poor project management & and one stupid decision about stadiums), capable of getting shit done, reasonably united, not obsessed with culture wars etc. On the other hand, NSW labor offered no compelling reasons for voting for them, and their recent past gives plenty of reasons to not vote for them for a long time. Their pathetic campaign seemed to be built entirely on the stadium decision. The voters saw all this, and chose not to take their frustrations with the federal libs out on the state libs. Had labor won, the voters would already have buyers’ remorse. As it is, they have saved the baseball bats for Morrison. The only thing that can save him is something Goebbels-like from the Murdoch press, and even that might not be enough.

LOL, “Clear Win in NSW”?!?! A 4% Primary Vote swing against the Coalition-in spite of the Opposition’s new leader only taking the reins in December of last year? I think you lot are trying a little too hard to make this look good for the Coalition.

This election is labors to lose and not the coalitions to win, and if labor does lose then it will be Bowen`s brain fart franking credit policy, there was really no financial gains there as it only impacted on the low income self funded retirees who will quickly make other arrangements to minimise or deflect that policy, but panicked all the other superannuants as to who would be hit next, a stupid policy with no real financial benefit to an incoming labor government but just making it much harder for labor candidates in electorates with a high percentage of retirees, its shortens/bowens michael daily moment and may prove a fatal mistake which is unfortunate as shorten has run an impeccable campaign up till that.

Your comments prove that you have no idea how the Franking Credits policy works. It actually impacts people with shares in the millions of dollars, not “low-income self-funded retirees” (who, btw, were sold out by Morriscum when he changed the asset test for part pensions, so his sudden faux concern for this group rings extremely hollow.

Now may I suggest you do some actual research, rather than regurgitating Murdoch propaganda?

bb…what crap! ‘…a stupid policy with no real financial benefit to an incoming Labor government…’

I wouldn’t call $6+ billion dollars (and growing) no benefit…Labor has other, and better, ideas for that money. Not to mention that the current status of franking credit legislation is just another rort instituted by little Johnny Howard to advantage his rich mates and gain a few more votes. Independent analysis shows that money from franking credits goes overwhelmingly to the top end of town…and Labor have already said pensioners will be exempt from the new rules anyway. It will have virtually NO influence on the election outcome.

It’s all about climate change/global warming…at least for anyone with more than half a brain!!

I’m a pensioner and WILL lose my credits as my ( minute) Pension commenced after 31st March. Normally a Labor voter I am quite conflicted as to where my vote will go (in Warringah) because of this particular issue.

Are you sure about that? Surely you’d need to have a very large shareholding to receive a refund of excess franking credits and thus unlikely to qualify for a pension.

The Cancer policy is paid for over the forward estimates by just 6 months of the franking credit change.

Still reckon there’s no benefit to the franking credit change?

Re electoral sentiment in NSW: I strongly suspect the good result for the Libs was substantially based on the very poor performance by the ALP leader Michael Daley – he was truly pathetic in that last week. My gut feeling is that NSW will be in line with the national trend which will be pro Labor. One caveat – the franking credits issue could well damage Labor to some extent.

Umm, how is a 4% swing & the loss of 4 seats a “good result”? NSW Labor has had 3 leaders in 4 years, so the Coalition should have been GAINING seats.