After the Coalition’s shock win at the federal election, many Australians are focusing on how key electoral concerns such as climate change and the economy will be affected. However, the Coalition’s third term will also have wide-reaching impacts on the digital world which have attracted little attention.

The Liberal and National parties have demonstrated a clear disregard for user privacy and security since forming government in 2013. What can we expect from the Morrison government? And are Australians’ digital freedoms, privacy and security at further risk?

Browsing the history

Issues surrounding digital rights have featured increasingly in mainstream media in light of data breaches, privacy scandals and increasing censorship around the globe. Despite this, many users are still unaware of how policy relating to the digital world can put their security and privacy at risk.

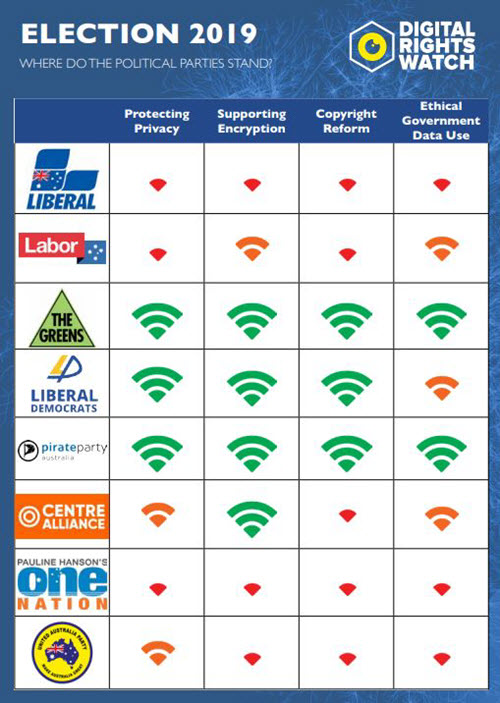

Before the election, advocacy group Digital Rights Watch attempted to rectify this by producing a digital rights scorecard for each major political party. Each party was scored on its stance on privacy, encryption, copyright and ethical data use. The Liberals drew with Pauline Hanson’s One Nation at the bottom of the table.

Why is this? For starters, mandatory data retention has been in effect since 2017. This enables intelligence agencies and government bodies to access metadata on the grounds of national security. Metadata is the technical data behind a communication, such as its form (SMS, email etc), the time and date it took place on, its duration, destination and where it was sent from.

Under law, all metadata must be stored for at least two years. Though metadata does not reveal the contents of a message, it provides anyone who can access it with significant insights into a user’s private life.

Last year the Coalition government also rushed through the Assistance and Access Act — legislation which allows government authorities access to the encrypted communications of anyone suspected of criminal activity, no warrant required. To facilitate this, Australian tech companies are having to build backdoors into encryption — which could make devices vulnerable to exploitation by cybercriminals. Unsurprisingly, it has caused outrage among these companies who are worried it will drive consumers to avoid Australian products.

Then came My Health Record. There are persistent concerns over the service which see Australians’ key health information stored in an online database. By storing this data online, My Health Record leaves Australians’ sensitive healthcare data vulnerable to hackers. This data can then be used to commit potentially devastating crimes such as identity theft.

These moves have left Australians’ private data open to access by not just government authorities, but any bad actor with the right tools and intent.

What to expect

Lizzie O’Shea from Digital Rights Watch told Crikey that some of these pieces of legislation are in fact direct violations of Australia’s human rights obligations under international law. “[These laws] have hampered free speech, taken away privacy rights and introduced instability and distrust in digital systems in both the private and government sectors,” she said.

O’Shea said that the Coalition’s track record does little to suggest digital rights improvements will be coming anytime soon. And this seems especially likely when looking towards global trends. Methods of limiting or monitoring online activity for the sake of national security are being increasingly adopted by totalitarian and democratic countries alike.

For example, site-blocking was recently introduced in New Zealand to counteract the circulation of violent content in the wake of the Christchurch terror attack. It has prompted discussions on whether permanent site- and content-blocking should be introduced, leading some to worry about how it could be used for government censorship.

With the expansion of China’s Belt and Road initiative furthering the exportation of advanced surveillance tech, and the recognised involvement of online platforms in political and terrorist acts, it seems likely that more digital legislation may be introduced to help protect national security.

What you can do

Through the passing of hastily drawn-up legislation and the introduction of databases such as My Health Record, Coalition governments have repeatedly thrown Australians’ digital rights under the bus. Thankfully, there are things Australians can do to help protect their data. Digital Rights Watch recommends Australians install a VPN, opt out of My Health Record and prioritise using apps and services that offer end-to-end encryption.

As well as taking immediate protective measures to stay secure, Australians can join civil society organisations such as Digital Rights Watch. There will be plenty more campaigning on the horizon.

Katherine Barnett is a researcher at VPN review site Top10VPN.com. Her writing focuses predominantly on global censorship, digital rights and cybersecurity.

(1) The (so called) ‘score card’ provides no information whatsoever in terms of HOW (e.g.) the Greens have endeavoured to oppose initiatives of the other parties. The ‘score card’, without definitive references is one grade up from a finger painting.

(2) “Coalition governments have repeatedly thrown Australians’ digital rights under the bus” ought to have been augmented with ‘compliance of the Opposition’. It took more than two!

(3) Fewer adjectives and more facts would have provided the means to evaluate the article’s claims against “My Health Record”

(4) The article OUGHT to have been located in a global context and not in a “we-them” context of puerile sour grapes; a presentation that is becoming rather typical on these pages nowadays.

(5) A nod to the objectives of Five Eyes would have also enlightened the reader in respect of the subject topic.

Overall : a dismal and uninformative piece of writing.

It should be understood that, bad as it is that the government knows as much about you as you do yourself, it is far more deleterious when it (assumes that it) knows MORE than you do.

Even worse, and distressingly common indeed not ‘normal’ – see credit rating agencies, is when the data hoovered up is not only incorrect but deliberately so.

The government uses the British Admiralty rating system (A-F/1-6) for data evaluation in which A1 is confirmed to F6 which is inuenedo, rumour and malicious.

The vast majority of Intel held by spooks, cops & the alphabet soup agencies is below C3.

Ponder that.

… as well as innuendo.