In their own words, the Marist Brothers are “dedicated to making Jesus known and loved through the education of young people, especially those most neglected.” It’s an admirable mission statement, but one that is hard to reconcile with the evidence delivered to the 2016 royal commission into child sexual abuse:

- 154 Marist Brothers were officially accused of child sexual abuse between 1980 and 2015, and many of them have been convicted or had claims paid out to victims.

- 20% of the Marist Brothers order between 1950 and 2010 were paedophiles.

- Claims of abuse against the Marist Brothers accounted for a quarter of all claims received by religious institutions.

- 486 people made a claim of abuse against the Marist Brothers between 1980 and 2015.

- The average age of claimants at the time of the abuse was 12.

- 89% of these claims identified one or more religious brothers as a perpetrator.

Founded by the French priest St Marcellin Champagnat in 1817, the Marist Brothers religious order has run 95 Australian schools, including 12 boarding schools, since 1972. Over this period, Marist brothers trained hundreds of male teachers who were posted to its schools across the country every year. Among these Marist Brothers were many fine teachers who didn’t abuse children. But there were many who did.

To try to comprehend how a single religious order could produce the scale of human devastation revealed at the royal commission, Inq went to Denis Doherty. A former brother now in his 70s living in Sydney, Doherty was a tall, stocky 18-year-old when he first arrived at the large farmhouse known as The Hermitage in the mid-1960s. This teacher’s college, or novitiate, located in Mittagong in the idyllic, misty NSW Southern Highlands, was run more like a boarding school than a vocational training centre. Its prevailing culture was punitive, prone to favouritism and outbursts of violence. Doherty remembers once being grabbed by the ear by the deputy master for failing to sweep his room properly. He said “it was so violent and so sudden” that the incident instilled in him a culture of fear.

Doherty was typical of the young, fresh-faced teenagers who arrived at The Hermitage between the 1920s and ’70s. It was a rite of passage for hundreds of Australian boys, mainly from devout Catholic families, who left their friends, families and schools to join the Juniorate of the Marist Brothers. Many of them were spotted by “vocation teams” of senior Marist Brothers who visited schools to bolster the numbers joining the order.

The recruits lived in a furtive environment. As one Marist Brother told the royal commission, it was a culture of “don’t ask, don’t tell.” Another brother, Ambrose Payne, described the prevailing sense of secrecy as “part and parcel of the culture,” citing advice given to him as a young brother: “Never ask a brother where he’s going, where he’s been, and where did he get that from.”

The boys at The Hermitage lived in a cavernous dormitory with rows of iron bedsteads on either side, a wooden locker per student, and a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary standing in the centre of the room in a niche in the wall.

These young boys had minimal contact with their families. On the days they weren’t working in the boiler room or the laundry, cleaning, or picking vegetables, they were schooled in the inappropriateness of certain songs and books, participated in “The Great Silence” where they were forbidden to talk for hours, and given lectures about the holiness of celibacy.

This was where they grew up and where their ideas about sexuality were formed and moulded. They were discouraged by their teachers to have any intimate relationships, snatching whatever affection they could get in secret, starting a pattern that continued throughout their lives as Marist Brothers. And if they were one of the unlucky ones, they were preyed on by their superiors.

From this cloistered culture, graduates were dispatched to schools across Australia that were totally controlled by the Marist Brothers, with very little scrutiny from the state.

After decades of this kind of life, the emergence of the Vatican 2 reformation in the 1980s brought the church into relative modernity — postulancies, including those run by the Marist Brothers, began to evolve into institutions that offered more normalcy and contact with the outside world — but by then it was too late for the victims. That’s because decades of repressed life inside the Marist postulanices had already taught and enabled numerous terrible offenders.

From loyal brother to ostracised whistleblower

Denis Doherty’s first teaching role was at a school in Kogarah in the southern suburbs of Sydney. He began teaching grade four, where there would often be more than 50 kids in the class. The pressure was intense: the brothers woke up in their tiny bedrooms at 5.30am, went to chapel at 6am for mass, then spent a full day in the classroom. “There was a lot of unhappy people there,” Doherty told Crikey Inq. “We were supposed to be living in a community, there was this emphasis on community, of the Marist family, but it just didn’t exist.”

Because the brothers had taken a vow of poverty, chastity and obedience, he said they felt dependent on the church for their livelihoods. “There was a feeling … that you would end up in dire poverty if you left. You were always dependent on the people who held the purse strings, that’s how it worked. People who were totally unsuitable stayed because there was nothing else they could do.”

Doherty remained a devoted brother to his order for more than a decade. Then, in 1973, he turned whistleblower against one of his own.

At the time, he was the principal at a primary school in north Queensland. He became concerned about the actions of one of his teachers, brother Gregory Sutton, who was showing signs of predatory behaviour. Doherty says that when he raised the alarm he was treated like someone who had a personal grievance against a colleague. And Sutton would go over his head to complain to a more senior figure at the school.

Doherty regrets he didn’t do more to sound the alarm, but said he was so overworked it was hard to pay attention to anything else. And, he says, Gregory Sutton was clever.

“Sutton had a train set and the boys that he liked, he would get them to come down and look at the train set. And he would go down there and leave his class vacant,” said Doherty. “And because I was teaching full time, even though it was happening in the same building, I didn’t know it was going on.”

Sutton’s behaviour became more brazen as the year went on. He would make preparations to take children away with him on weekends. When Doherty tried to stop him, he would go over his head for approval from a more senior brother. Sutton, he said, “didn’t just groom the victims, he groomed the people around him.”

Doherty became ostracised by the other senior brothers. He was seen as a troublemaker. “The more I thought we were on the wrong track and the more I tried to change it, the more resentment I caused from the others,” he said. “They also had an enormous compassion for people who had faults. So if someone was an alcoholic, for example, they would be compassionate and thoughtful about that.

“If a brother was accused (of child sexual abuse), there was an automatic pack response to protect him. You had this sort of feeling, well this brother is someone who gets along well with children and likes children, and likes them in a platonic sense, and is popular with kids. Then there’s this suspicion. So there are a lot of factors going on, trying to figure it out.”

This “pack response” was on display when he raised concerns about Greg Sutton to one of the most senior brothers at the time brother Charles Howard, the Sydney provincial, during one of his visits to the school in 1974. “When he came in 1974 I said I was very worried about Greg’s behaviour and his propensity to have teacher’s pets,” Doherty said. “He said to me that they would send him to Sydney to get counselling.”

Howard even wrote Doherty a letter the following year, in an attempt to calm his concerns. “Don’t worry too much about the Greg situation,” the letter said. “We will be able to handle that for next year. Thanks for what you do for him, despite the difficulties.”

But when Doherty followed up the issue in 1976, the response was swift and stern. Doherty was “rudely and savagely told … to mind my own business,” the commission heard.

In 2014, Doherty told the counsel assisting the royal commission he was “extremely angry that I had told the brothers in the 1970s and they did nothing and Greg went on to do some of the most dreadful things”. As he put it to Inq: “We were so fucking naive. There were some very serious suspicions that arose from his behaviour and nobody chipped him, except me.”

The royal commission found Doherty had not specifically defined the behaviour as child sexual abuse in his complaints to the hierarchy, but concluded in any case that they should have acted on his concerns of inappropriate dealings with children, including Sutton “wrestling” with children and taking them for rides in his car on his own. “We are satisfied that Brother Doherty conveyed his concerns about Brother Sutton to [another superior] Brother Holdsworth,” the commission said, “but do not conclude that those concerns were expressed as ‘interfering’ with children.”

Doherty said he personally knew some of the 154 Marist Brothers accused of child sexual abuse: “There were brothers who I got along quite well with, and suddenly they’re in jail.” He said he believes the culture of celibacy, alongside the protectionism provided by the church, helped the behaviour to flourish — but he rejects notions that there was a “paedophile ring”.

By 1989, the net was closing in on Sutton. Knowing that police were investigating Sutton for sex offences, the provincial of the Marist Brothers Alexis Turton put Sutton on a plane to Canada to receive treatment and counselling, in the process removing the suspect from the legal jurisdiction of his crimes. It would be several years before Sutton was extradited back to Australia. But after he was, in 1995, he was convicted of 67 sexual offences against 15 children, which included performing oral sex on girls as young as five. Of the 21 complaints made to the order by Sutton’s former students, 18 were sustained. He was sentenced to 12 years in jail, and in 2017 he was convicted again for offences committed in Canberra.

In 2014, Sutton gave damning evidence to the royal commission. He accused the order of blatant cover-up, claiming that in August 1989 Turton had called him to a meeting and told him he was being investigated for offences at a school in Campbelltown, outside Sydney. Within four days, Sutton says, he was put on a plane to Canada.

The commission heard that after his treatment, he was given a job as an administrative officer in a school in the US city of St Louis. He told the royal commission that in 1992 he received a call from Turton informing him that an arrest warrant had been issued but that he “should stay over there and live your life”. Inq approached the Marist Brothers to verify this conversation however Provincial Head Peter Carroll declined to comment.

Meanwhile, Turton, the man who was responsible for decisions that helped move Sutton overseas, and who interviewed many suspected child sex offenders, remains a senior brother within the Marists, an order that is now trying to wipe its slate clean.

What are the suspected paedophile Marists doing now?

So what is the status of the 154 suspected or confirmed Marist Brothers child sex offenders who appeared on a list produced by the royal commission after it received data from internal documents provided by the order itself? The internal records covered all cases from 1980 to 2015. Brother Alexis Turton was asked to amend the document and put an “A” next to any name that had admitted child sexual abuse to him. At least 10 brothers had admitted their criminal behaviour to him. Under cross examination, Brother Turton told the commission he had talked to 52 of these brothers over a period of about 17 years as Provincial from 1989, and in his professional standards role from 2002 to 2012.

This list remains secret and has not been released to the public. Whether any of those brothers remain in senior leadership positions in the order, or are in locations close to children, is unknown

The list is not subject to freedom of information; the only way it would be released is if the Marist Brothers decided to do so. Many orders and dioceses in the United States have decided to release all the names of offenders, for transparency.

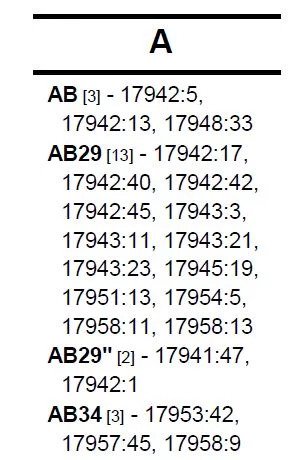

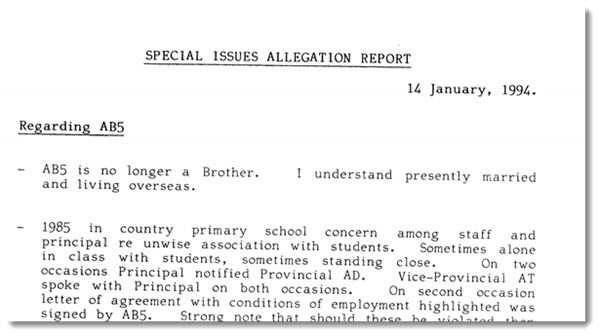

During the 2016 royal commission, documents were also produced that revealed the Marist Brothers used special codes for offenders in their internal communications. Each one was allocated a number. AB29, for example, was the code for brother Dominic O’Sullivan, now a convicted child sex offender. The code was like a special language used by the hierarchy, making it harder for anyone outside the inner circle to know who they were talking about.

A despicable past, but what of the future?

The Marist Brothers have apologised for their behaviour. The order’s Provincial, Peter Carroll who has been in the role since 2015, is working hard to repair the damage. As part of this reinvention, most schools have removed clerics from teaching positions.

Carroll was unambiguous and deeply contrite in his mea culpa statement to the royal commission:

We cannot deny the unpalatable truths that have been revealed about the Marist Brothers’ responses to child sexual abuse, vulnerable young people were sexually abused by Brothers, criminal activity look place, our response was entirely inadequate, the serious effects of sexual abuse were unrecognised, leaders failed to take strong decisive action, victims were offended against by means of aggressive legal processes. Our responses were naive, uninformed, even callous at times.

So what’s happened since then to address the structural problems within the Marist Brothers’ ecosystem? At the royal commission, Carroll outlined the reforms he has put in place to make their schools safer:

Every Marist Brothers school must have a child protection policy and a code of conduct, compliant with the relevant standards … those standards require that there is ongoing training and professional development, and an ongoing review of child protection strategies.

To understand how these reforms have changed the Marist Brothers, Crikey Inq put a number of questions and a request for interview to it’s Provincial, Peter Carroll. He declined to answer those questions, but supplied the following statement:

“I appreciate your invitation for an interview but must respectfully decline at this time. There are some points I would like to make. A number of matters you raise relate to Case Study 43 of the royal commission. The royal commissioners decided to delay the public release of this report to avoid prejudicing any current or future criminal or civil proceeding and as such it is not appropriate to make any comment on any related matter at this time. The Marist Brothers are committed to ensuring any person abused in our facilities receives justice and open acknowledgement of what they and their loved ones have endured. To this end we are a participating institution in the National Redress Scheme. My apology on behalf of Marist Brothers to those who experienced abuse is unreserved and enduring. That any child could be so harmed and failed when in the care of the Marist Brothers is a matter of profound sorrow. Today our mission is supported by mandated and voluntary policies and procedures to protect children. Central to this are the provisions of mandatory reporting legislation which applies to all individuals, religious and lay alike.”

This year and next will be a hard one for the Marist Brothers with several senior brothers before the courts for either child sexual abuse or cover up. These men held senior positions inside schools, including that of principal. These trials will reveal much more about the historical inner workings of an order, now desperately trying to improve its image with the public.

Inq would like to acknowledge additional research contributed by Anne Worthington, for this article.

Anyone seeking help after reading this article can contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 and Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636.

I’m a former student, Marist brothers Kogarah in fact during the 70s.

It was widely rumoured and generally accepted part of going to school that it was best not to find yourself anywhere alone with 1 other brother or lay teacher.

The vast majority of brothers and lay teachers were good, or at least reasonable people. Still, apart from paedophiles they housed some vicious souls, barely containing volcanic anger, a few desperately mentally unwell people who on occasions threatened to jump off roofs and balconies, during school hours.

It was a clusterfuck, no two ways about it. School was something I survived.

Could have been worse. Could have gone to Marist brothers Penshurst, as a number of friends did, where the notorious ‘Dolly’ Dunn was working his evil with a couple of accomplices.

I know some of the victims.

The Marist Brothers should be outlawed like the motor cycle gangs. They have barely done less harm.

Peter Carrolls letter doesn’t fill me with confidence. He pays lip service to being sorry, but not being able to discuss anything at all just because a case is before the courts seems to be way these days to avoid scrutiny in business, politics and religion these days. Religious leaders have become masters of obfuscation, but the truth will out eventually even if justice is evaded.

And of course they will all answer to God on Judgement Day… He(she?) won’t accept any obfuscation. Besides he(she) knows the truth already.

Excellent reporting bar one major error, Vatican 2 Ecumenical Council occurred in the sixties not the eighties. 1962-1965 to be precise. Perhaps it took the Marists until the eighties to take on some of the requisite changes, as indicated, on board. That would not have been abnormal, regrettably.

These articles provide a sound and helpful analysis of clerical child sexual abuse in Catholic institutions. However, the elephant in the room in all these cases is the failure of Catholic institutional leaders to respond to knowledge of the abuse of children in accordance with the Christian principles to which their very lives were supposedly dedicated. They hid the evil and allowed it to continue. Why did leaders not apply their fundamental values to such apparent evil? The answer lies in an examination of the ‘clericalist’ culture of status and the lack of accountable, transparent and inclusive practices in the governance of the Church. This culture and dysfunctional governance is further illustrated in the failure of the Church to even address that key question today: “Why did leaders not apply their fundamental values to such apparent evil?” Apologies, regrets, and new processes go so far but also serve to distract from demands for answers to that key question.

Why, also, do we always talk in the past tense. Even now religious leaders know damn well who the, as yet unexposed, perpetrators are and are actively protecting them. As i’ve mentioned before, these are not honourable men or institutions.