As the Catholic Church attempts to reinvent itself as a safe place, the roots of that reinvention will almost certainly be found in seminaries like Missionaries of God’s Love. A series of unprepossessing brick buildings tucked away in a quiet suburb in Melbourne’s east, this is where 18 young men live for seven or more years as they train to become priests.

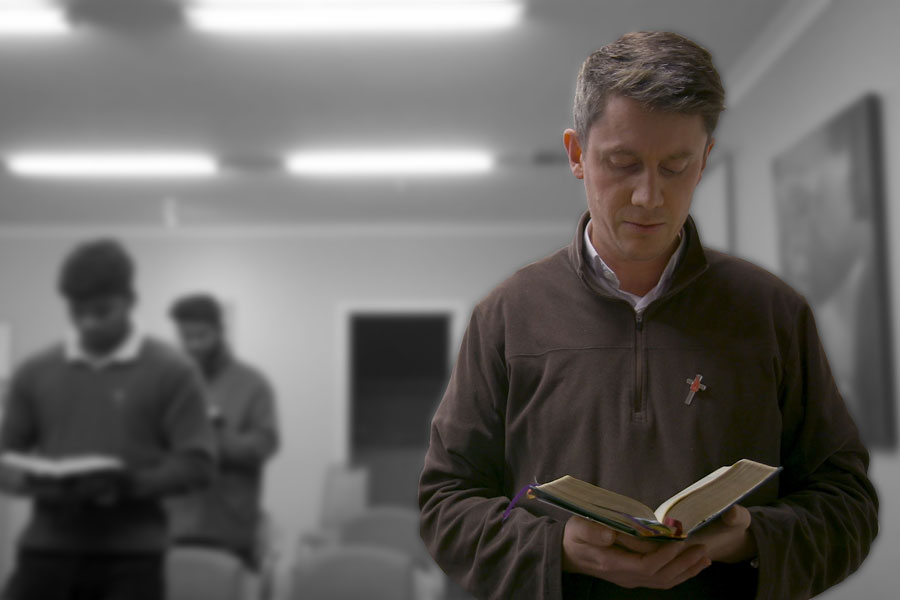

And if the church ever does achieve that reinvention, its culture change may be guided by priests like Father Daniel Strickland. Behind friendly brown eyes and a soft voice is one of the youngest Catholic priests in Australia’s religious history. He looks a decade younger than his 41 years. Originally from Perth, he was ordained in 2008 and today is the director of Missionaries of God’s Love.

Historically, seminaries have been isolated places that demanded obedience and conformity, shunning interaction with women and the mere mention of sex. These factors, the 2016 Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse found, led many priests to commit offences against children. 7% of all Australian Catholic priests have been accused of sexually abusing a child.

“It’s been disastrous,” Strickland told INQ. “There is a whole shame around the Catholic church. I joined 20 years ago and this has been my whole entire experience, going through that. It’s been hanging over us.”

As Strickland welcomes us to his ‘home’, he carefully steps over a puddle to avoid splashing his uniform leather sandals. It’s a dreary winter day, but he showcases his warm smile. “It’s warmer inside, come on in,” he says, leading the way through a labyrinth of neat rooms toward the chapel. He sees himself as a mentor, guardian and coach for the seminarians. They all wear brown pants, brown jumpers and white shirts paired with leather sandals which stay on even when the temperature dips to single digits. Toes turn blue in the cold.

Laminated sheets of how to report child abuse are tacked to the wall at Missionary of God’s Love. Seminarians are encouraged to talk about their concerns and feelings daily. Psychosexual maturity is routinely discussed.

At the same time, the seminary is bound by Vatican documents that dictate the way it is run and the moral code that must be taught. Despite scientific evidence of intersex people and Klinefelter syndrome, transgenderism, according to those documents, doesn’t exist. Homosexual acts are sinful. And celibacy is compulsory for Latin Rite seminarians.

We are here at Strickland’s seminary because it’s more welcoming than the 11 other seminaries contacted by INQ. It’s an unusual and distinctive quasi-monastic, Catholic Charismatic order. Most others either rejected our requests for an interview or ignored our calls. One offered us restricted access, but with a media escort.

Strickland’s approach to formation — the Four Pillars of Priestly Formation are based on four aspects of life: human, spiritual, intellectual and pastoral — appears to be almost defiantly compassionate and understanding. The students say they feel they can genuinely raise their concerns or troubles with him, that he’s trustworthy and honest and wants to fix the church’s problems.

Students are chosen for their devotion to “the call” to priesthood. They train for two years in Canberra before being accepted to the seminary and undergo psychological testing, as well as getting police and working with children checks, which we are told have become more stringent since the Royal Commission.

“The capacity here is 22 people … we don’t want to go more than that because then it can start to take on an institutional feel,” says Strickland. Six students are Australians, the rest come from abroad.

The students wake up at the crack of dawn. Mass begins just after 6am, followed by prayer and an hour in silent contemplation. No phones buzz and there are no digital distractions. The time drags. They eat breakfast together, catch up and discuss their schedules, followed by classes in theology, philosophy and ministry at the nearby University of Divinity, a private collegiate university of specialisation which receives Commonwealth Government funding.

The curriculum is governed by the Australian Qualifications Framework, with council members appointed by six Christian churches. Students can gain diplomas, bachelors and masters in ministry, theology, leadership and philosophy. When they return, they pray, cook on a rotating roster, then have a few hours free to study or relax before praying again and heading to bed. Every second Monday is reserved for the Brotherhood, to discuss personal development and struggles.

“They don’t have a lot of time off, actually,” Strickland says, adding that one Sunday a month the men have an “unstructured day” where mass is the only obligatory event. While the students are free to spend their time as they choose, they don’t have funds of their own. They can’t go to the movies, catch public transport, or buy a meal without requesting funds from the common purse, controlled by a senior brother.

“I just don’t want money being wasted on things,” says Strickland.

They can use shared computers and social media, but filters and restrictions are in place. Calls home are limited to a couple of times a week — less, for the international students, to save on costs. They freeze their bank accounts following first vows and, when they are ordained to the priesthood, give away their money and assets to the church, charity, or family. None of this is unusual for life in a seminary.

It’s all part of the three vows each student takes when they join Missionaries of God’s Love: chastity, poverty, and obedience. But the seminarians don’t see these vows as restrictive, each echoing the same phrase — “it’s a gift.”

* * *

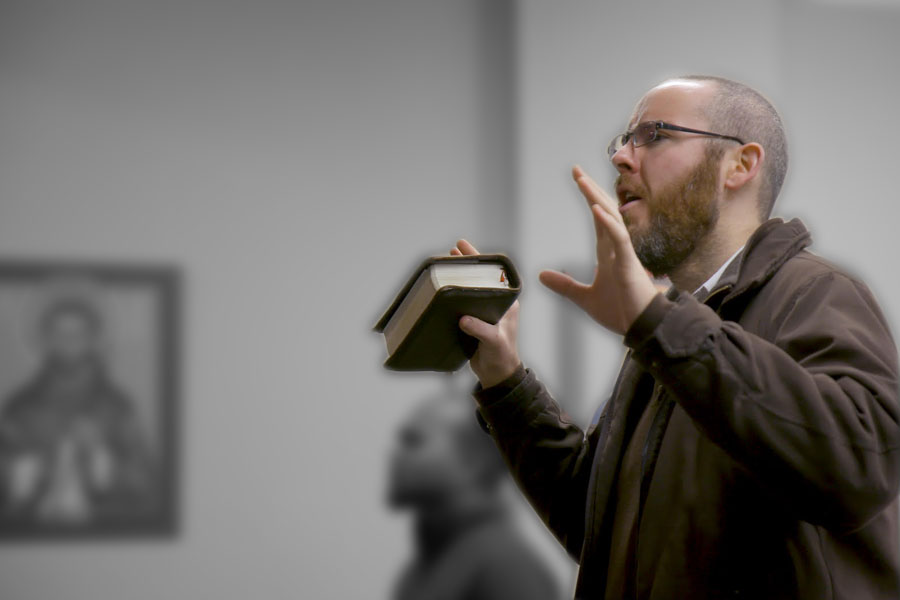

Cameron Smith is 29, in his final year of training, soon to become ordained to the priesthood. He grew up in a devout Catholic family in Melbourne’s suburbs. He’s tall, with brown stubble, glasses, and a friendly face. He looks like he could easily envelope you in a large bearhug, but unlike Strickland, refrains from anything more intimate than a handshake. Like the other men, he said he joined because of “a calling”.

Smith completed a science degree at Monash University in Melbourne before becoming a seminarian. Like all of the other students, he has experience in the outside world and an air of confidence, but his hands tremble. He’s had some short term relationships. “I guess you could say I had a few flings,” he says.

Celibacy wasn’t attractive to him initially — he wasn’t even sure if he could commit himself to it — but now he feels it is a gift. “I have a call to give myself to the Lord in the fullness of my sexuality,” he said. But he acknowledges it’s normal to slip up, and while masturbation is a sin, it’s one of the more common sins.

The royal commission has recommended introducing voluntary celibacy for diocesan clergy to minimise risk of harm to children, stating, “All Catholic religious institutes in Australia … should implement measures to address the risks of harm to children and the potential psychological and sexual dysfunction associated with a celibate rule of religious life”.

As Missionary of God’s love is monastic, celibacy isn’t an option even if changes to Canon law are changed. But Strickland believes that risk is minimised in his seminary.

“What celibacy can create, if it’s not lived well and supported, is a culture of secrecy,” he says. “So part of the reason for regulating smartphone usage is the accessibility of pornography. And the fact that it can kind of become a private world with a smartphone.”

Thinking about sex is not taboo at the seminary. One student explained that when he was struggling with intrusive sexual fantasies, Strickland arranged for him to see an external psychologist. “Our main focus now with chastity and celibacy is that we don’t want this seen as an imposition,” says Strickland. “If you don’t want to do this, you’re free to walk out the door. If you can’t live it maturely and responsibly, you’re going to hurt people. And we’re seeing that time and again in the church.”

Celibacy is a “discipline” of the church, which means it can be changed, not a “dogma”, which is set in stone, divinely revealed, truth from God. Universal compulsory celibacy dates back almost nine centuries, when the church decreed that priests were banned from marrying, in part to prevent their wives or children from making claims on a priest’s property so it could be retained by the church.

The students at the Missionaries of God’s Love seminary still believe celibacy is an important aspect of their religious devotion. Fourth-year student Suraj Mattappalli-Jose says even if the Pope amended the canon law, he would remain celibate because otherwise “it would mean that I’m divided in my availability to be there in my ministry.”

Mattappalli-Jose joined the seminary from India six years ago following a messy relationship break-up. Feeling lost and unfulfilled, he attended a retreat where a priest told him he had been chosen. “I experienced a heat on my head,” he says. “It was a very warm feeling and I was kind of overwhelmed with that experience.”

For Mattappalli-Jose, the sacrifices and risk are worth the reward. “If you hold onto your past, it doesn’t let you go forward. But once you let go of things of the past, it releases you to go much further.”

The vow of poverty is taken seriously and incorporated into every element of the seminary. The living room consists of six saggy green couches arranged in a circle, pointed at each other instead of a TV. The students shop at Aldi, choosing items on sale and taking turns cooking for everyone. Every week, they pick up leftover bread from the bakery. Dinner is chicken drumsticks, potato and beef stew, rice and powdered curry. It’s served in the dining hall on mismatched floral plates and wobbly tables.

Obedience, the third and final vow taken by the prospective priests, is problematic, admits Strickland.

“Obedience is a funny thing in the Western world because it can seem to be seen as oppressive,” he says. “But for us, it’s what holds us together. It’s a sense that ultimately we do want to be surrendered to what God wants for us.” But as he acknowledges, “the church has seen terrible abuses of leadership in the name of obedience.”

Conformity, the royal commission found, increased the risk of child sex abuse, with “segregated, regimented, monastic and clericalist environments … based on obedience and conformity” producing clergy who were “cognitivley rigid”.

For Smith, obedience at the seminary is an internal pressure, not an external one. “Obedience is something that needs to be a personal decision and we make that vow ourselves. A person can only kind of give that consent and be obedient if they have possession of themselves. Obedience requires certain personal freedom.”

It’s this level of individuality and personal choice, he believes, that separates modern seminaries from their troubled past.

Strickland sits at the head of the table, cracking jokes and facilitating conversation, turning beetroot red whenever he laughs — which he does often and freely. Over dinner, the men joke and jostle with one another. One student explains that for him, leaving his job as a political communication advisor to join the seminary was a “road to Damascus moment”. When another student asks over the murmur of conversation “What’s that?” Smith shakes his head with a smile. “We’ve been meaning to buy him a bible.”

Mass is celebrated daily in a simple chapel, emulating their vow of poverty. The room is devoid of anything intricate. The altar is a simple wooden construction draped in green, the colour of the season, and white satin. Prints of balding saints line the walls.

Smith picks up a guitar, peppering the sermon with acoustic psalms. The confident students belt out the lyrics. The shy ones sing under their breath, knowing they’ll be teased for not singing later on. At the end of each song, the men bellow in tounges, singing gibberish and letting the euphoric feeling they call God flow through them.

* * *

Kevin Peoples hated his experience at the seminary. He found it antiquated, cultish and extremely worrying. “It’s amazing that there weren’t more paedophiles,” he said. “It was a dysfunctional organisation producing people unable to form relationships.” Older than most students by almost a decade, he joined when he was 25. He’s now 82 and retired.

Peoples joined St Columba’s seminary, an impressive sandstone building surrounded by 1200 acres of bushland in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney, in 1965. He stuck it out for three years before he left because he found the teachings too concerning to continue — “I was introduced to a different God in the seminary than the one I knew.”

A few years after Peoples left St Columba’s, Father Joseph John Farrell joined. In 2016 he was convicted of nearly 100 child sex offences against 12 victims.

According to Peoples, the seminary was built on a culture of fear of sex and women. Contact with women — even thanking the nuns who cared for the 200-odd students — was forbidden. Sex was never discussed and “no-one talked about celibacy … no-one mentioned how lonely it would be.” The church, he said, “produced inadequate people who didn’t know how to fit into society.”

The royal commission found the factors contributing to offending by Catholic clerics was immaturity, sexual identity confusion, lack of peer relationships, alcohol abuse, and personality vulnerabilities. The report found religious figures and teachers are the most common perpetrators in institutional settings.

A US survey in 1971 of nearly 300 randomly selected priests who were evaluated for development to psychosexual maturity found that just 6% had the sexual maturity of an adult. And a recent research project by Dr Olav Nielssen and three other Australian psychiatrists which supported the theory that celibacy, church culture, and the need for intimacy were important causes of paedophilia amongst clerics.

Nielssen says:

All but one of the offenders entered the church as teenagers and did so for a range of reasons including confusion about sexuality as well as the influence of charismatic church figures and altruistic ideas, at a time when the prestige of the Catholic Church was very high. Many were starved of affection and were not prepared for lives of celibacy, and received little in the way of guidance. Some of the offences did not involve obvious sexual gratification, and appeared to be seeking physical affection.

Isolation, as well as the banishment of sex, was a huge part of Peoples’ experience at St Columba’s seminary. Students could write letters to their families, but weren’t permitted to seal the envelopes themselves. “We had no personal friends,” he said. “We could never even walk with just one other man, we always had to walk in threes. You couldn’t walk into another student’s room. The atmosphere was that homosexuality could break out at any moment.”

Sociologist Frederic Martel interviewed over 1500 priests, bishops and cardianals, estimating 80% of Vatican staff are secretly gay. “The Vatican has one of the biggest gay communities in the world,” he writes in his book In the Closet of the Vatican, adding there is a “system built, from the smallest seminaries to the holiest of holies — the cardinal’s college — both on the homosexual double life and on the most dizzying homophobia.”

“If you were a Catholic boy in central Italy, or Australia or around the world in the 1950s and you suddenly realised you were attracted to other boys, what would you do?” says Noel Debien, a religious specialist, former seminarian, and ABC journalist. “You’d think you know what, well I can’t do that ’cos that’s wrong — it’s evil. If I become a priest I don’t have to deal with that. If I remain celibate, I don’t have to deal with it.”

In the US, there is a growing acknowledgement of the presence of gay clergy at every level of the church. “There is a homosexual culture, not only among the clergy but even within the hierarchy, which needs to be purified at the root,” Cardinal Raymond Burke said last year. Bishop Robert Morlino of Wisconsin reinforced that view: “It is time to admit that there is a homosexual subculture within the hierarchy of the Catholic Church that is wreaking great devastation.”

Gay priests, bishops, and cardinals are “caught in a whiplash of relative toleration embodied by Francis and hostility exemplified by his conservative predecessor, Pope Benedict XVI,” wrote the respected gay Catholic journalist Andrew Sullivan in a milestone piece in New York Magazine earlier this year. “The 2005 ban on gay priests and seminarians is still in force and, in fact, was affirmed by Francis in 2016. As a result, almost all gay priests are closeted, for fear of being targeted or terminated, which makes them uniquely barred from entering the discussion. They listen as they are talked about and scapegoated — often in deeply offensive ways and always as if they were not one of the church’s key ramparts.”

Another attraction to students to become seminarians is the spiritual change that purportedly occurs when they are anointed to the priesthood. Priests have the ability to consecrate bread and wine into the body of Christ, can forgive people of horrendous wrongdoing and, upon ordination, will metamorphose into apparently superior beings.

Once anointed, they are “ontologically changed”, transformed spirituality, set apart from the laity. This practise and approach can be adopted by both clergy and lay people, and is known as “clericalism”. The royal commission found clericalism increased the risk of child sex abuse, finding the “culture of clericalism … on the rise in some seminaries.”

Noel Debien trained for six years before leaving the seminary and sees this attitude in significant numbers of recently-ordained students. “They want to wear collars. They want to wear birettas. They want to celebrate the old, Tridentine mass in Latin and push the altar against the wall. Whatever the reform is,” he said, “it seems to be going the opposite way in some places.”

But three years on from the royal commission, a national protocol for screening seminary candidates has not been established. Each seminary in each diocese implements teachings in different ways. At the Missionaries of God’s Love seminary in Melbourne, Strickland has tightened the already-strict admission process and is trying to improve identification of early warning signs of child sex abuse. “We need to have training in that kind of area,” he says.

“We try to get some objective feedback about what [the applicants] are like, rather than just our subjective experience of them,” Strickland says, though refrains from divulging specifics

“Thee big checks are psychological testing, working with children checks, police checks … then a lot of it is just around conversations, really.” Strickland says he looks for resilience, capacity for personal growth, and sexual traits. Those with either promiscuous or “deep-seated homosexual tendancies” — a phrase used in Vatican documents — are weeded out.

In her testimony to the royal commission, psychologist Sister Lydia Allen (who in 2017 was investigated by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency and allegedly practiced while unregistered) said, candidates with “deep-seated homosexuality” consider their sexuality to be part of their identity, and therefore are unwilling to be “formed” or to be “in one heart and one mind” with the church. On that basis she believed seminarians should be rejected.

“I have not heard of [deep-seated heterosexuality] being a problem,” she says.

Heterosexuals with an active sexual past would also be rejected from the seminary, Strickland said.

“If you’ve lived a promiscuous way of life, well there’s a value system underneath that. It would raise a serious warning sign.”

“I was super grateful for the royal commission,” he said in a spirit of glass-half-full. “It’s given us a chance for external objective regulation, feedback and accountability, to say your processes are pretty hopeless.” Whether they are still pretty hopeless, and whether that brings, in his words, “cultural change in the long term” to seminaries, “is still to be seen,” says Strickland.

The world is watching.

“Once anointed, they are “ontologically changed”, transformed spirituality, set apart from the laity. This practise and approach can be adopted by both clergy and lay people, and is known as “clericalism”. ”

The details of this aspect of Catholic belief and practice really need widespread public examination. It just seems totally pernicious. It is one thing to train a group of people to be spiritual leaders and to give them status and respect. It is entirely another to pretend that such training confers an “ontological” difference (i.e. superiority) on the graduates. And only men, celibate men at that, are eligible! How can such a doctrine withstand the light of day? Do other denominations and religions practise anything similar?

The broader community looks askance, rightly, at sects led by charismatic leaders – but at least in such cases the charismatic “superiority” is conferred by the followers, and can be withdrawn if and when the penny drops. Not so with “clericalism”.

And on a lesser point, how can this “practice and approach” be “adopted” by a lay person? How does that work?

It’s a complete no brainer. A quick look at the Gospel accounts and epistles will reveal that at least 75% of the deciples and apostles of Jesus were married men and women.

Celibacy may have been a personal choice for some, but it certainly was never an OT or NT doctrinal requirement.

In the mid-70s my first job at 15 was working in a catholic bookshop in Brisbane. They sold both catholic religious odds and ends, such as communion wine, religious icons and theology books but also secular text books for catholic schools. Every Christmas period we would get a bunch of burly seminarians to help out with the Christmas and New Year rush. Probably five or six of them and they were always good fun, these trainee priests.

You see, in the year before their final vows these guys were released into the community to see if they wanted to push on with the program. So, after five or six years in what amounted to a closed male community they were pretty much freed for a period. What I saw was a bunch of young men let lose. They got on the grog, they went to the footy and the races and most had “girlfriends”, or if not girlfriends then facsimiles of such relationships. More than once I covered for these young blokes hiding about the building sleeping off hangovers. Mostly they seemed normal and fun. Then by February they were gone never to be seen again, and next November a new bunch would arrive and it was on again.

I’ve often wondered about all these young men and the schizophrenic life they chose for themselves. Years and years of monastic life, a short year going to restaurants, movies, beer and family and then a professional emotional recluse for however they could stand it. Sometimes forever. What a life….?

It would seem that the less inviting the institution, and it would appear to be the case amongst most religious organizations, the greater the appeal. If mouldy bread and rancid water were the obligatory rations, membership would quadruple.

“Despite scientific evidence of intersex people and Klinefelter syndrome, transgenderism, according to those documents, doesn’t exist.”

May I just point out that Klinefelter’s is a form of intersex variation, and neither have anything to do with being transgender. Most intersex people (people whose bodies are not clearly exclusively female or male) report their gender identity as female or male. Transgender people are usually clearly male or female biologically, but their gender identity does not align with their biological sex. Transitioning to live as their self-perceived gender may or may not involve changing the body to better align with the gender identity. And neither biological sex nor gender identity determine a person’s sexuality: sexual/romantic attraction, behaviours and/or identities (e.g. gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, etc.)