Australia could soon enter the lucrative international high school education market, pawning its certifications, assessments and teacher training to institutions across Asia, the Sydney Morning Herald reports this morning.

A report from the NSW Education Standards Authority (NESA) in January highlights the economic opportunity for selling Australian education, with the English-medium school market in traditionally non-English speaking countries expected to generate almost US$95 billion by 2028 (nearly doubling from US$47 in 2018).

Australia’s curriculum is currently offered in just 89 overseas schools, representing 0.01% of the market. It generated just $521 million in 2017. This is compared to $20 billion made from tertiary education, the country’s third largest export.

But Australia lags in high school education compared to other countries. The system is more expensive and achieves lower academic results compared to international competitors. Just what would selling Australia’s education mean for our economy — and is it viable?

Market competition

The largest English-speaking curriculums offered worldwide are Switzerland’s International Baccalaureate (IB) and UK’s O and AS-A levels. Both have continued to grow in popularity, with the number of IB programs offered worldwide increasing by 39.3% between 2012-17.

Cambridge Assessment International Education offers the UK O, AS and A-levels high school education to 10,000 schools in more than 160 countries — charging fees for annual participation, exam entries, teacher training and publications.

The IB is offered across nearly 5000 schools worldwide. Despite being registered as a non-profit agency, the IB had US$124.8 million in assets as of 2017, generating a US$43.2 million surplus between 2016-17. Annual fees for a high school diploma program cost each school US$11,650 per year; assessment registration fees generate the most income, costing $119 and $172 respectively for each student’s registration and subject fee for assessments.

NESA notes that Australia could sell products including the HSC and VCE assessment materials, curriculum materials, and regulation products including quality assurance processes.

The Australian edge?

According to NESA, Australia’s key education markets exist in China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam. The IB, by comparison, is offered at fewer than 200 schools across India and China.

Australia’s secondary education system is one of the most expensive in the world, ranking eighth for annual expenditure by OECD and partner countries. Australia spends around $12,000 on each educational institution’s full-time equivalent secondary student, compared to an OECD average of $10,000. Despite the costs, the returns are low with education standards dropping.

Contrary to NESA’s report which states “Australia is at the forefront of international education … The quality of Australian education is highly regarded”, UNICEF’s latest Innocenti Report Card ranks Australian secondary education at the bottom third of high-income OECD countries, ranking 38 out of 41 for quality education. Reading rates have been in decline according to the PISA reading rate scale, with students struggling with phonetics.

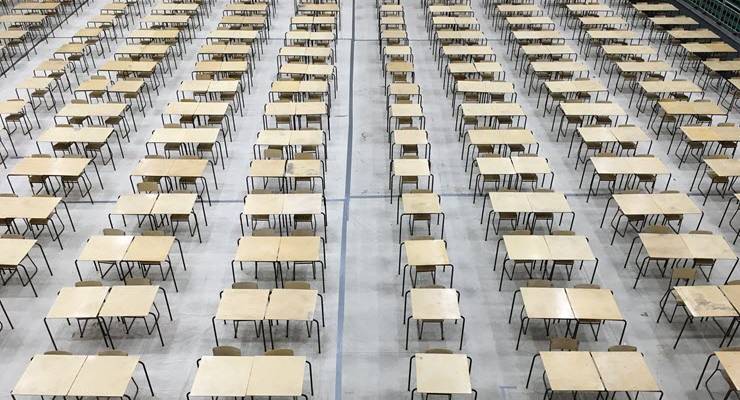

Australian high school students have some of the highest schoolwork-related anxiety in the world, according to a PISA wellness report, with 46.9% saying they feel “very tense” when they study compared to an international average of 36.6%.

What could we gain?

Exporting education, NESA reports, could raise revenue through fees and funnel international students into the higher education sector. Though the sample size of schools is currently extremely small, 94% of students who sat Victoria’s high school education certificate overseas went on to study at Australian universities.

Universities, however, have been struggling with international recruits. Foreign students have been failing courses, many with sub-par English language skills. Universities are highly dependent on the fee revenue of overseas students, sparking concerns over the country’s reliance on China (with Chinese students making up almost a third of the international student population).

Soft power is a significant advantage, with NESA noting “there is substantial potential for strengthening relationships and growing soft power across the [Asia] region”.

This certainly isn’t the last we’ve heard of the issue.

Do you think Australia’s secondary school curriculums should be sold overseas? Send your comments to boss@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name.

The only “advantage”, if you can call it that, that Australian education has over other international competitors, is that it has seemed, up until recently, to be a short cut to getting PR or Australian citizenship. As that illusion disappears, along with the realization it’s a con and international students are just being used as a TEMPORARY source of cheap labor, so will Australia’s “advantage” disappear and the disastrous consequences of the so-called Dawkins revolution will become apparent.

The Columbo Plan of the 50s was a boon, to both this country and the region because the education on offer was excellent.

Post Dawkin it became an commodity and since the Rodent allowed any spiv to claim to be a college or place of higher learning the standard ahve been in a race to the bottom, purely for the income.

As noted above, even the worthless degrees don’t matter much as the main aim is back door immigration.

This suits the employer class and the “students”.

Australia loses in so many ways.

Selling off high school spots to cashed up neighbours is a good way of teaching currency kids all about real heads down, socially anxious, in it for life grinding.

But will the first XI ever be the same?

I wonder if “Australia’s secondary education system is one of the most expensive in the world” simply because very high and unwarranted subsidies are doled out to the so-called private sector.

Politically, as much else in our politics, Education has been played as a wedge issue. At the more fundamental level has been its commodification, you can have as much education as you can pay for. As for anxiety levels these figures reflect the rise in youth mental health issues and as a society it behoves us to pay some attention as to what is going on here, there is something not at all right within our society.