I’m at Varuna, the National Writers House in the Blue Mountains, when I get a message that the manager of the Bendigo Writers Festival wants to speak with me. I have a sinking feeling I know what the outcome of this phone call will be, and sure enough, several hours later, I find myself agreeing to withdraw from my appearances at the festival in August.

While all it takes is a laptop, or a pen and a piece of paper to write, one also needs encouragement, space, time and, most crucially, the acknowledgement that engaging with and interpreting the world around you is a worthy, even necessary, project. Varuna, the big yellow house in the mountains, is that acknowledgement made bricks and mortar.

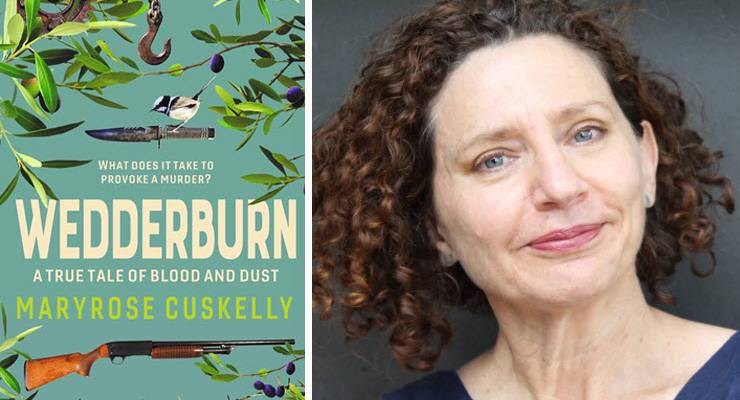

Given that I was only a couple of days into what I hoped would be a week of discovering the shape of my next book, it was unnerving and distracting to be confronted with the reality of being excluded from the festival on the basis of objections to my last, Wedderburn: A True Tale of Blood and Dust.

I did have forewarning. Late last year, following the publication of Wedderburn, I accepted an invitation to appear at the festival. Bendigo is the closest regional centre to Wedderburn, where the triple murder at the centre of my book occurred. Given the blowback that had come my way through social media and in a pretty relentless email campaign that my publisher bore the brunt of, I suspected there might be those who would be less than happy to see me invited to the festival, but it was months away and I hoped the furore would have abated by then. And it had.

Most writers, I think, embark on a writing project seeking to understand, rather than create a stir. At least, that’s what I did. Through an accident of knowing someone who knew someone, I became interested in the terrible events of October 2014, that ended with Peter and Mary Lockhart and Mary’s son Greg Holmes losing their lives at Wedderburn in Central Victoria.

I began tentatively attending pre-trial hearings concerning the accused murderer and testing the water as to who in the community and among the victims’ family and loved ones might be prepared to speak with me.

I became aware, early on, that there were differing perspectives on motive, the characters of both the victims and the man who admitted to killing them. It was plain, too, that in any community, particularly one as small as Wedderburn, that such a horrifying act of violence would be a destabilising and sometimes polarising event. In addition, of course, the grief, shock and trauma of the those who loved both the victims and the perpetrator would be immense.

I understood all this; only a fool would not. I persisted as gently and carefully as I could in my research, interviewing and writing, because understanding what drives people to commit acts of extreme violence and the ways individuals can become isolated within their communities, and building empathy with those who suffer are, I believe, worthwhile and important aims.

Following its publication, I promoted Wedderburn through numerous speaking engagements in regional Victoria and met only respectful and engaged discussion about the tensions in some rural communities, the darkness that lies in all human hearts and the possibility of rebuilding shattered lives.

As the Bendigo Writers Festival approached, I was feeling more confident that my appearance wouldn’t cause a fuss, particularly as none of my sessions were discussing the book directly. Then I was alerted that the festival had received complaints from some of the victims’ family members about my inclusion. There were demands that I be dropped from the program.

The campaign then became relentless. Vociferous attacks and threats to disrupt the festival escalated. State and federal representatives were contacted, Bendigo councillors were lobbied and pressure brought to bear in ways that were, I’m led to believe, intimidatory and aggressive.

In retrospect, I capitulated more quickly than I would wish. But I think it was also inevitable. I was asked to withdraw, and I acquiesced. I hate to think of other festival participants and attendees being intimated or made to feel unsafe because of my presence.

At the time of Wedderburn’s publication, and in the process of writing it, I had to confront the question as to what right I had to tell this story which, it could be argued, was not mine to tell. It’s a question that many writers, and certainly, all true crime writers must answer for themselves.

I believe, as do my publishers, that the intent of literary true crime is to generate empathy and to contribute to discussions that we are already having in our society including questions about the role of gender and power in violence; about our capacity to recover from trauma; and the difficulty of establishing objective truth.

Writers festivals must remain places where divisive and difficult topics can be debated with nuance and respect. I am disappointed that I will not be able to contribute to discussions on some such subjects at this year’s Bendigo Writers Festival and dismayed that festival organisers and members of the Bendigo Council have been subject to intimidation.

I still have a few days left at Varuna and I will cherish them, because I continue to believe that writing and the ongoing quest to understand and interpret the world matter.

Maryrose Cuskelly is the author of Wedderburn, published by Allen & Unwin.

What is this about in five paragraphs?

Because Crikey automatically spikes comments with links, I have reformatted the link. Substitute a full stop for the word “dot” and read all about it.

www-dot-who-dot-com-dot-au/triple-murder-in-victoria

Thank you for writing about such difficult matters. I look forward to reading your book.

Yes sounds like quite read.

I reckon there’s a book looking at what drives true crime writers.

Money and ego

Looks like the Streisand Effect is now wide spread – try to excise something from the public sphere and attract all kinds of crazies.

Yet it is also of a part with no platforming and the general flight from Reason.

I find this to be an extremely disingenuous, passive-aggressive article! In the emails to the publisher that you refer to as, ” in a pretty relentless email campaign that my publisher bore the brunt of,” a question was asked that was never answered. Which ethical processes were followed during the creation of this book and to assist in the decision to publish? There was no answer, but instead a bland statement that you thought you were undertaking a “humanistic study of people and community and small towns”. In Australia, researchers undertaking human studies are expected to acquire ethics approval from an appropriate body. This crime had been solved and written about many times – the objection to this book is that it is unethical and the plot drawn together with salacious gossip. Which you admit to at the end of the book. This ‘dog and bone’ strategy may be legal – but is it ethical? Had an ethics panel been employed; or, MEAA Code of Ethics or the Press Council guidelines been appropriately followed, I believe, the situation we face today wouldn’t exist.

I think a fairer assessment of the situation would be that those complaining do not have a concern about a book being written (another book chapter already exists), but the unethical and unnecessary story concoction was inappropriate and dishonest to both the people you’ve written about and the reader. This perception of dishonesty seems to continue in this article. “I’m led to believe, intimidatory and aggressive.” … “I hate to think of other festival participants and attendees being intimated or made to feel unsafe because of my presence.” This type of statement is unfair, unfounded and unethical! On what grounds could you possibly make such an alarmist and defamatory statement – unless of course your goal is to once again use innocent family members to draw attention to yourself and your book in your efforts to make a career for yourself?

Are you implying, that anyone, without qualifications in psychology or social work can sneak around a town, collecting gossip, rely on interview of only 2 of the 10 children of the deceased, provide no extra information about the murderer that wasn’t already available, without qualifications to do so make extremely incorrect connections or assumptions about violence, (that in real terms is dangerous for many women – I have actual qualifications in this area that allow me to make this comment!) and then complain when family members try to say that’s not fair and what rights do they have to privacy and dignity when their private stories had nothing, whatsoever, to do with the crime?

I don’t know what the family members will do next – but I hope there’s a complaint (or several) to every relevant code of ethics panel and politician to ensure that this scenario is not thrust upon another innocent family member. I have observed that many True Crime writers, perhaps those with a journalism background, do a far better job of writing these stories. But, there are examples such as this one that cross the line of ethics and fairness. The True Crime industry needs to better regulate itself and if it can’t then laws need to be enacted to protect the vulnerable. I hope that all those that intend to purchase this book know that they are contributing to the unnecessary suffering and breach of privacy of persons (including children) who had no part in the commission of the crime in question. The family didn’t show up at your events, didn’t follow you around, but you complain when you intended to come to their town and to events that up until now they had enjoyed participating in. Why are your rights greater than theirs? Why do you see fit to cast yourself as a noble victim? The only ethical thing to do would be to pulp the book and let them live their lives in peace!

Streisand effect indeed. Looks it up, yes it’s available on Kindle

https://www.amazon.com.au/Wedderburn-true-tale-blood-dust-ebook/product-reviews/B07DX5JSW4

The Streisand effect is real – but how ethical is it of an author to try for it after causing her victims so much pain already? Given the complaints about ethics and the construction of this book I don’t find it surprising that this was the author’s tactic. The overall scenario is that victims of unethical crime writing processes have no options available to them – complain and the book is advertised – say nothing and the industry will never learn to regulate itself, or poor practice, and further innocent people become the unnecessary fodder of this type of activity. There are many in the industry with a good level of ethics but can’t say that I’ve seen it in this case – mmmmm what to do? I hope the family push every politician possible to ensure that something is done to regulate the industry if it won’t call out and regulate its own.

I’d be uneasy about the government legislating about the content of books, there’s too many things in such legislation that could be abused by the government themselves.

I agree – but if the industry won’t implement, uphold and monitor for ethical standards what is the alternative? Humanistic studies in other settings require an ethics panel – this should be developed as a minimum. What happened with this book shouldn’t be allowed to occur – suggestions to safeguard the private lives of the vulnerable, innocent and irrelevant to the crime?

.. umm, “what is the alternative? “.

Freedom, in all its untidy, unquiet exuberance?

I’m not going to comment further without actually reading it, which defeats the purpose of the argument in a way. Be back after I have

Right, I’m thinking some people in the town don’t like the book because it reveals things they would rather were not. And that’s really not a good enough reason. Don’t like it? Don’t read it. I’m not sure if I’m going to read past the sample or not, but that’s more because I don’t really get into “true crime” books.