Is Sydney’s golden age as Australia’s premier city over?

It took me less than 24 hours into a Melbourne/Naarm holiday to realise I had to move here.

I’d tagged along with my sister at Edinburgh Gardens, and it remains one of the most delightful days of my life. Friendly, hip 20-somethings were chatting about their arts/media jobs and playing pub footy in dopey unicorn costumes. The weather was warm without choking you in humidity. Of course, Brisbane/Turrbal had all of those things (minus the weather), if in much smaller quantities. Still, something snapped that day, and three months later, I’d moved.

My journey was a carbon copy of hundreds of frustrated young creatives, a form of internal migration that, if World Population Review is to believed, helped Melbourne eclipse Sydney as Australia’s largest city in late January.

Sorting the stats

Let’s get the figures sorted. World Population Review has Melbourne at 4.87 million, compared to 4.85 million. But those population figures, based on UN World Urbanization Prospects, differ significantly from the ABS’ recent estimates for June 30 2018. The latter put Melbourne at 4.96 million and Sydney (which also includes the Central Coast) at 5.23 million.

Going off the ABS’ latest figures and growth rates, Melbourne won’t officially become Australia’s largest city until 2026.

But regardless of where you draw the line — the ABS also excludes Geelong from the Greater Melbourne Area — Melbourne has been on track to overtake Sydney since the early 2000s, and an exponential growth rate over the past decade has meant it arguably got there 10 years early.

Professor of Demography at Macquarie University Nick Parr argues that Sydney would still be considered larger with or without the Central Coast but, with a growth rate of 1.8% compared to Melbourne’s 2.5%, has suffered from an exodus of retirees and families.

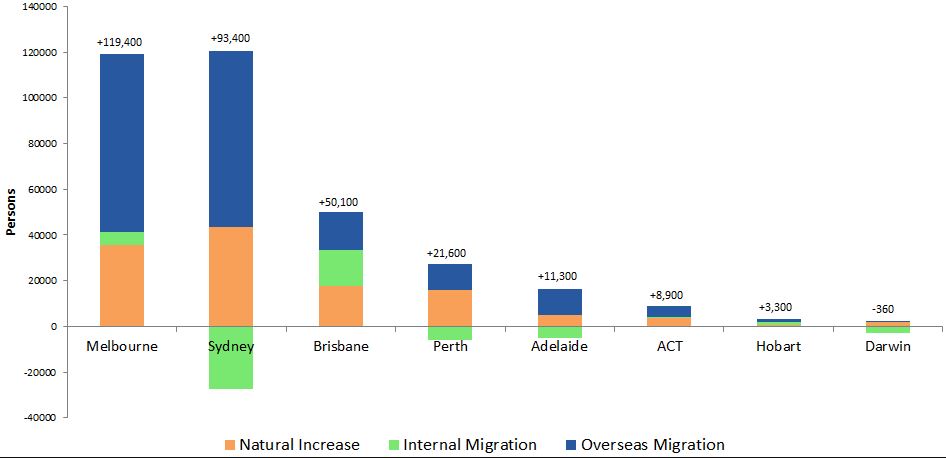

Melbourne, on the other hand, saw a net internal gain of 5971 from 2017 to 2018, while experiencing Australia’s largest international migration gain (77,624) and the second highest natural increase (35,826).

“In the mid-1990s, Melbourne was actually losing people elsewhere, while in the 20th century they’ve turned that around,” says Parr. He argues that an improved economy, job prospects, relative housing prices to Sydney, and the end of Western Australia’s mining boom have drawn people from other states. International migration, he says, has benefited from the Victorian government’s being “far more proactive” with Australia’s skilled migration programs.

Sydney still hit Australia’s total highest birth rate and second-highest international migration gain, but saw a net loss of 27,300 people to other states in 2017-18. Parr believes they mostly left over housing prices or to retire in Queensland (Brisbane, either due to housing or that aforementioned heat, hit Australia’s highest internal migration rates).

The other capitals tell their own stories, of course. Darwin’s net exodus of 2800 people more than offset its natural increase of 1800 and net overseas gain of 640 for a total loss of 360 people. While obviously complicated, Charles Darwin University’s Northern Institute found last year that work and family issues dominated reasons for leaving the Territory.

Demographers speaking to the ABC early this month also found Hobart’s net internal migration gain a surprise considering its unemployment levels, while anecdotally conceding that culture and housing prices are likely drawing people to the state.

Population pressure

The question now becomes how Sydney and Melbourne cope with these changes going forward. Demographers note that, without geographical barriers, Melbourne will continue to sprawl, while the Sydney Basin — formed in part by the Blue Mountains — will necessitate a rise in vertical communities.

While more houses are easier to build than skyscrapers, Melbourne’s horizontal growth will create challenges with commutes. Initiatives like that $50 billion suburban rail loop, announced last August, are designed to connect outer suburbs’ commercial, educational and residential hubs.

Parr notes more will have to be done in both cities to foster suburban hubs, where transport to the city centre is not as vital for work or lifestyle, but save for some “bravado” on urban planning governments have failed to follow through on planning research.

Finally, he notes that, with “the number of lower house seats allocated to state populations, more members of parliament drawn from Melbourne will foster some electoral consequences”. These would presumably relate to both federal spending and, as many artsy Melburnians would have it, culture.

This change has been a long time coming, but are both cities ready to deal with the consequences?

Crikey will be publishing stories all week on the Sydney/Melbourne rivalry: the facts, the figures and the fallout. NEXT: What makes a successful global city?

Just to add to applet’s comments on “rivalry”. I don’t know anyone in Sydney who thinks anything but fondly about Melbourne when they think of it at all, but I don’t know anyone who wants to move there. Melbourne people feel insecure, and need to reassure themselves that they’re hipper, funkier than anyone else. This is fine for them. Whatever helps them get through the grim months when no AFL is being played. Sydney’s faulty in all sorts of ways. It’s had some state governments of both shades that have been real stinkers and the mates have far too much power. But the climate’s nice, the harbour and associated rivers and beaches are very beautiful, people can have conversations in which football is never mentioned, the food and the coffee is no worse than Melbourne’s and most people enjoy their lives without worrying about anywhere else. Of course Crikey, being utterly Melbourne-centric, sees this as a competition, but people in Sydney don’t. Why bother?

“Of course Crikey, being utterly Melbourne-centric, sees this as a competition, but people in Sydney don’t.”

Ever wondered why Crikey (and much of Australia’s alternative media) arose in Melbourne rather than Sydney?

Because the rent was cheaper and there is bugger all else to do?

This is old news, I think. There was a time when Melbourne was down in the doldrums and was jealous of Sydney. It’s not like that now, and hasn’t been for nearly 20 years.

In some ways this is going back to the way things were; from the aftermath of the 19th century gold rush to the early 20th century, Melbourne was bigger than Sydney.

The real question, as the article implies, is how you react to these increased numbers. Melbourne has a strong civic tradition that responds well to maintaining public amenity, but of course money talks when it comes to building approvals and there’s always pressure to sell off more green space on the city’s edge and let it sprawl further.

At least we now have a Victorian Government that’s less obsessed by budget surpluses and is willing to borow money to get infrastructure built which should have been constructed decades ago. The bad news is that much of it is wasted on new/widened roads which will only induce more congestion.

I’m cautiously optimistic that Melbourne will handle its growth well; certainly the inner-city and CBD are still pleasant places to live with good public transport, even with the inevitable increase in medium and high-density housing. Perhaps Sydney’s problems with dodgy apartment blocks will act as a wake-up call across Australia about the dangers of privatising the approvals process, and that hazard will be wound back.

Though the Melbourne CBD is absolutely chockers with people all the time now, it does have a wonderful multiculutural vibrancy as a result. There’s a great sense of fun and activity in the air, and the big international student population adds to that. The city is wonderfully improved since the grim recession days of the early 1990s.

As a former long time Melbourne resident, now a long time Sydney resident, I don’t ever recall anyone in Sydney giving a rat’s arse about the elitist concept of ‘rivalry’.

Prior to leaving the Melbourne I was thoroughly over I went elsewhere in Aus to live before ‘trying out Sydney’. Upon instantly liking the ‘negatives’ of Sydney, I realised the ridiculous lie about rivalry that had been spun. We choose a balance of what we want, every city has its share of shitty and fabulous features.

Australia’s modern city issues all stem back to state governments having no control over immigration, and federal government class that has sold their responsibility to the corporate and educational sector.

Amid a word-rage attack may I rise from my hardscrabble bed and reach out to ask why “going forward” is so consistently thrown into sentences where it doesn’t belong, like reins on a car. Look at this: “The question now becomes how Sydney and Melbourne cope with these changes going forward”. Did anyone imagine that we were interested in them coping with these changes going backward? Put the word “will” between “Melbourne” and “cope” and leave out the absurd “going forward”. Go forward to your merchant bank, you bastard.

10+

With you!

Well you can keep both of these ‘mega-cities’, as far as I’m concerned. Just visiting to see family in Melbourne a couple of times/year, always makes me relieved to be back home.

VERY happy living in a much smaller, and more civilised, ‘small capital’ in OZ, thank you!