In 1932, at the peak of the Great Depression, Australia’s unemployment rate hit 20%. Today, that’s about the unemployment rate in Fairfield, where around one in five people who want a job can’t find one.

When we hear about unemployment, the picture too often focuses on the national rate, currently 5.2%. This hasn’t changed much over recent years, so it’s easy to miss the fact that other countries are doing much better. When she visited Australia, Jacinda Ardern was polite enough not to mention that New Zealand’s country’s unemployment rate is around 4%. That’s also the rate in Britain and the United States. Countries that underperformed Australia during the Global Financial Crisis are now outperforming us — and by a significant margin.

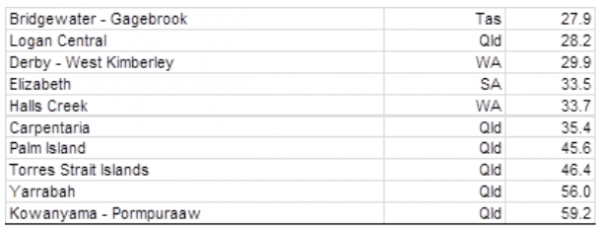

But when we look across regions, it becomes clear that averages can conceal as much as they reveal. Fairfield’s unemployment rate may be the worst in NSW, but it isn’t the worst in Australia. In Victoria, unemployment in the Geelong suburb of Norlane is 22%. In Queensland’s Logan Central and the Hobart suburb of Gagebrook, unemployment is 28%. In South Australia’s Elizabeth and Western Australia’s Halls Creek, it’s 34%. On Palm Island and the Torres Strait Islands, unemployment is 46%.

This means that there are communities across Australia where more than a quarter of those who want work cannot find a job. That’s a national scandal.

After Australia came through the GFC without a recession, some conservatives bemoaned the fact that our economy had missed out on the cleansing fires of a “good” recession. Under this way of thinking, severe downturns clear out the “dead wood”, and make way for new growth. It’s an approach that sees recessions as bushfires: painful in the short-term; necessary in the long-term.

But it’s hard to share that view if you’ve spent time with people who struggle to find work — who find themselves on the margins of society, hoping for a job opening that fits their skills. The reason that many of us on the progressive side of politics are concerned about the red flashing lights right now is that we see the waste of human potential that comes with excess unemployment. Joblessness isn’t just another economic indicator; it’s a marker of how many people are missing out.

Highest unemployment rates in Australia

The cost of unemployment falls disproportionately on some of the most vulnerable Australians. Among those with a mental illness, unemployment is at 8%. For those with profound disabilities, the jobless rate is 9%.

For anyone who doesn’t speak English well, or didn’t finish year 10, the unemployment rate is 13%. This means that for low-educated Australians, the labour market today is worse than it was for the average person at the height of the early-1990s recession.

For Indigenous Australians, the jobless rate is 21%. Consequently, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people face a job market that’s worse than the national job market was at the peak of the Great Depression, in 1932. Is it any wonder we’re struggling to close the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians?

Rather than patting themselves on the back, members of the Morrison government should heed the alarm bells that are ringing about our underperforming job market. In 1945, prime minister Ben Chifley committed Australia to achieving full employment, and for a few decades, the nation succeeded. But today, the jobless rate is again too high — inflated by inadequate infrastructure investment, a flawed education system, excess monopoly power, and a lack of start-ups.

The cost of unemployment is never borne by the most advantaged citizens. Instead, the pain of joblessness is felt most acutely by communities in Fairfield, Norlane and Halls Creek, by people with worse health and fewer skills, and by Indigenous Australians. Unemployment is a social justice issue, exacerbating inequality and undermining the social compact. Unless everyone who wants work can find it, the economy isn’t working for everyone.

Andrew Leigh is the Shadow Assistant Minister for Treasury and the federal Member for Fenner.

Those QLD results really speak to why Adani is such political poison for the ALP. Even though the jobs are pathetic, they are jobs. Something is better than nothing, even if that something has consequences.

I do wonder how low the result must be in some regions for the ‘average’ to offset such high results or is it just more Government cooking of books.

The unemployment figures used by this politically and economically corrupt government are lies and pure fiction, during the depression those unemployment numbers were accurately based on people not having paid work, todays figures are percentage seasonally adjusted bullshit( including someone who has only worked an hour in a fortnight but then classed as employed and based on that ridiculous calculation), and the very low amount paid by new start is cruelly designed to force people to take extremely low paid jobs or starve, and the 20 applications a month stipulation to qualify for that newstart pittance is impossable to achieve because they cannot afford a phone or fares and transport to apply either, what is being foist upon a dumbed down populace is akin to the old British fuedal system of master and low paid servant.

If two thirds of the workforce in Elizabeth has a job, what are they doing right? Presumably some jobseekers have left Elizabeth and found work elsewhere – just as the grandparents of many of today’s residents of Elizabeth left the UK to find work in Australia. The economy is changing and jobseekers need to adapt. Not all can as readily as others, but what’s missing from Andrew Leigh’s numbers are accounts of people who adapted by leaving Elizabeth (etc.), starting their own businesses, branching out into new occupational areas over the last decade or two and how they fared. Surely thousands have done this.

And why head this article with a picture – albeit an iconic one of Al Capone’s soup kitchen – from almost 90 years ago?

Andrew is not usually such disempowered a hand-wringer.

On the statistics, generally not successfully. As always, the eager blame, plus the pretence of choice, the aim being to deny the problem thus denying the need for action.

Well, a 2018 analysis of ABS data by the Centre for Future Work revealed that for the first time, it is only a minority of workers who enjoy permanent, full time employment with access to sick leave and holiday pay.

An employment vulnerability index developed by three academics from Griffith University, Charles Darwin University and Newcastle University found not only that brutal austerity (such as no benefits for the first six months of unemployment) would make the situation worse for unemployed people in already-vulnerable suburbs, but also that trades training is crucial to countering spatial patterns of unemployment. Spending cuts generally plus State and Federal cuts in trades training cause a “double whammy” of job market inefficiency and a lack of region-specific information about job opportunities for already disadvantaged areas. Just like Japan, where since the early 1990s the proportion of temporary workers has doubled to nearly 40%, harming wages, skills, productivity and aggregate demand.

The growth of part-time employment – which overwhelmingly is women – means that there are more people aged 25-64 in employment now than at any time in our history. But they are nobly under-employed. No choices there.

The true figures leads one to consider the political expediency of labelling all people on so-called “Newstart” as dole-bludgers. The reality is that if our government actually understood economics, they would know that an extra dollar in the hands of someone living week to week is circulated throughout the economy in full – leading to more jobs and more opportunities. If you starve out those without work, the economy shrinks and no-one wins. It’s not just about human dignity and the right to meaningful employment, it’s also about the betterment of society for all.

These figures comparing current unemployment numbers with the 1930’s ignore the modern invention of underemployment – people who might have an hour a week of work in some BS casual/gig ‘job’ and are therefore magically excluded from the ‘unemployed’ total. (Was little Johnnie the creative magician who started this?) Estimates usually put the number of underemployed as greater than the number of those (totally) unemployed. This means we need to more than double the above figures to arrive at a true comparison.

Andrew usually has more depth than this – or am I missing something?

Marcus L’Estrange used to be a regular contributor here on the issue of unemployment data. It was his specialty and he really knew the field and understood the politics involved – over a fifty-year period. Marcus, are you still around?