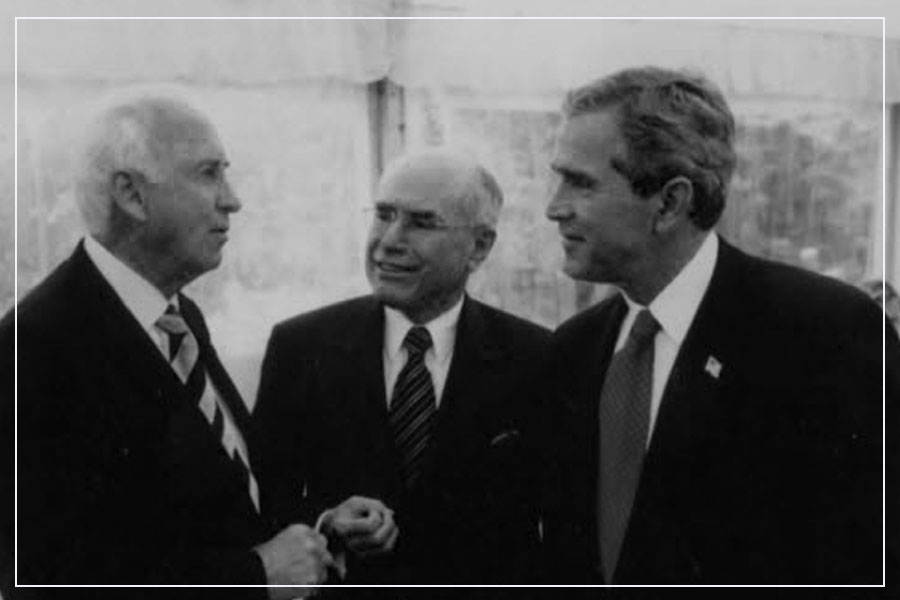

In a video tribute released shortly after his death, Paul Ramsay — known to his close friends as “Ram” — posed with a gentle, slightly off-kilter smile in picture after picture, standing alongside John Howard, Tony Abbott, Barnaby Joyce, even George W Bush and the former Indonesian president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

While Ramsay was incredibly influential and lived, in many ways, an extravagant life, he was invisible to most Australians. When he was occasionally mentioned in the gossip pages, it was usually alongside more high profile celebrities, like the time Elton John enjoyed a harbour tour on his yacht, or when Ramsay donated $300,000 to the Kevin Spacey Foundation at a charity dinner in 2011. But mostly he went by without recognition. This was how he liked it.

In a rare TV appearance in 2014, shortly before he died, he told TV presenter Ray Martin that as the chairman of one of the country’s biggest companies, he had never sought the spotlight. “Everyone would be after us,” he said with a wry smile, wearing, ironically, a bright pink sports jacket that would make even Gatsby blush. “I like to keep private, a low profile.”

Despite his taste for the finer things in life, Ramsay was far from your typical billionaire. For one thing, he was genuinely liked by almost everyone who met him, a rare accomplishment for a businessman who spent his entire life making deals. Even long after his death, most described him as a gentleman, someone who genuinely cared about his employees and colleagues, with the same friendly persona on the golf course as he had in the boardroom.

Speaking to INQ, Ray Martin described Ramsay as someone who, despite his incredible business success, came across as gentle, decent, almost softly-spoken. “His bedside manner was like a good country doctor,” said Martin. “He was more like the local priest than the local megalomaniacal billionaire.”

It was his belief in relationship building that underpinned his business mantra — look after people and the rest will follow. Etched in the walls of his company, it was known as the “Ramsay Way”.

The road from Burradoo

Ramsay was born in Sydney in 1936 and raised in Burradoo in the NSW South Highlands. A devout Catholic, he was educated at St Ignatius’ College Riverview in Sydney, where he would meet many of the people who remained alongside him throughout his entire business life: Tony Clark, Michael Siddle and Peter Evans. In one of his rare interviews, Ramsay insisted that “loyalty is far more important to me than intelligence”. After finishing school he started studying law at Sydney University, but left before completing his degree.

Ramsay did his first business deal shortly afterwards, asset stripping a small publicly-listed company he had acquired for less than its real estate value, according to a 1995 Sydney Morning Herald profile. A decision to buy Warrina House on Sydney’s north shore in the 1960s would set in motion a series of events that would make him extremely successful. It marked the beginnings of what would become not only the largest private hospital company in Australia, but a global group with 151 hospitals across the world. It would also make him extremely rich — his fortune rising by $1.04 billion to $2.7 billion the year before he died, putting him at number 11 on the BRW rich list.

But billionaires aren’t made by accident. The profitability of the private health sector depends heavily on government policy, and it was thanks in no small part to a series of reforms in the 1990s that Ramsay was able to go from business to empire.

In the early 1990s, the Keating government began selling off veterans hospitals. At the same time, Ramsay was keen to diversify his business and avoid an over-reliance on psychiatric hospitals. Hollywood Repatriation Hospital in Perth was the first to go in 1993, snapped up by Ramsay on a $500 million contract, resulting in redundancies for about 60% of the hospital’s 1200 staff and an industrial dispute with the Australian Medical Association. A year later, Ramsay acquired Greenslopes, another veteran’s hospital in Queensland.

It was the election of the Howard government in 1996 that created an incredibly fruitful environment for the private health sector. After Labor introduced Medicare in 1984, the number of Australians taking out private health insurance had been steadily declining. Private health providers frequently bemoaned a heavily regulated system that made it difficult for the sector to experience the kind of stratospheric growth and investment that was happening in the US at the same time. Even Ramsay, generally reluctant to make openly political statements, spoke out about the need for Australia’s health system to look more like the American model — one where the private sector played a greater role in managing service delivery and where Medicare operated “only as a safety net”.

The more limited role for Medicare was consistent with the Howard government’s preferred healthcare narrative. According to a recent Grattan Institute working paper, the Howard years were characterised by a belief that Medicare was an unsustainable financial burden. In order to relieve a perceived crisis, the Howard government created a series of “carrot and stick” incentives to direct more people toward private insurance.

In 1997, the Howard government launched the Private Health Insurance Incentive Scheme, which introduced incentives for low income earners to take out private health insurance, and a 1% surcharge on high income earners who didn’t purchase it. Two years later, the government introduced a 30% rebate for people using private health insurance, and a year later, the community rating program was ended. In 2000, Lifetime Health Cover was introduced, which allowed insurers to charge higher premiums based on the age when people took up insurance. With the prospect of higher premiums kicking in, some 3 million people rushed to get private insurance, boosting the entire health sector.

On the eve of the 1996 budget, when the first of these schemes was set to be announced, Ramsay’s rival Mayne Nickless saw its share price hit a two-year high. Within a year of the introduction of the 30% rebate, Ramsay Health Care’s profits went from $6.62 million to $16 million. In 1997, Ramsay Health Care floated. It was the second time the company had been publicly listed. Ramsay Health Care had floated in 1987, but after a sobering four years plagued by hubristic poor planning, heavy losses and a financial crisis, Ramsay was forced to obtain a court order allowing the company to go private again.

But the Ramsay story is one of opportunism and resilience. Thanks to a painful, tough restructuring process, Ramsay’s businesses survived. Their second float was far more successful. Having learnt from earlier mistakes, and operating in a supportive business environment, the company surged. By 2007, Ramsay had joined the billionaire’s club.

The US connection

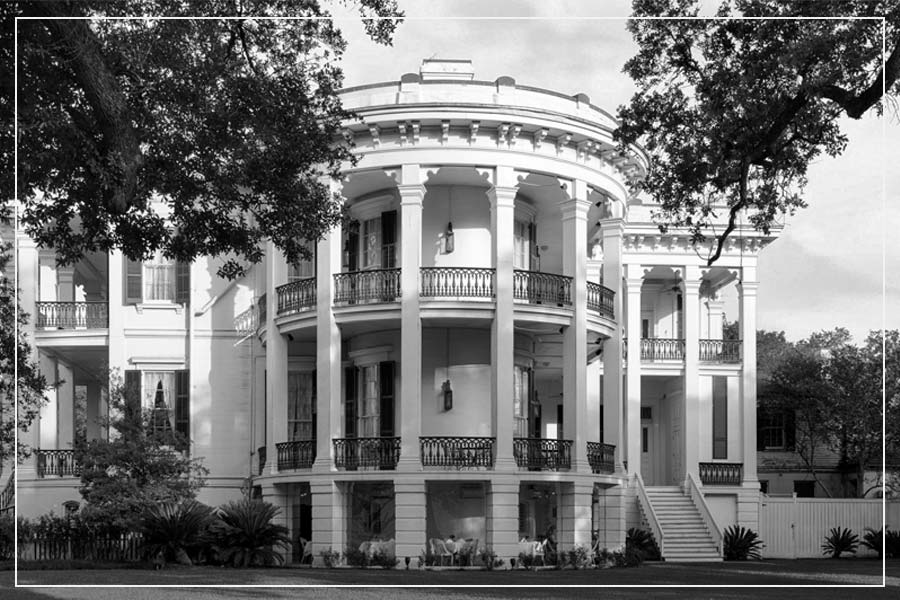

On the banks of the Mississippi River outside of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in one of the poorest corners of one of America’s poorest states, sits Nottoway Mansion, a sprawling Italianate plantation house, all gleaming white marble and manicured lawns. Built during the Antebellum era by one of the region’s most prominent slave-owning families, Nottoway, it is now the largest such mansion left standing in the South, and a grand monument to nostalgia and forgetfulness. Buses of tourists come for a dose of Gone With the Wind Southern charm, and leave with little acknowledgement of the plantation’s bleak history as a place which was built by, and housed, people owned like cattle.

One such visitor who fell for Nottoway’s charm was Paul Ramsay. In the 1980s, the Australian private health baron stayed there on one of his many trips through the South, where he was building a new arm to his empire. He was so smitten that he bought the place overnight for a cool $4.5 million, then spent up to $20 million over subsequent decades to turn Nottoway into the sepia-tinted luxury resort it is today.

Ramsay’s relationship with America, from his restoration of Nottoway to his business interests in the Deep South, is largely an unknown story that started in the late 1980s when his private hospital empire was steadily growing in Australia and Hong Kong. In 1987, Ramsay bought a controlling stake in Health Care Services of America, an Alabama-based company that ran psychiatric hospitals, and weeks later added a health maintenance organisation servicing Hispanic communities in the Miami and Fort Lauderdale areas.

While Ramsay’s Australian businesses struggled in the early 1990s, his companies in the American South were surging. For his efforts in reversing the fortunes of a once struggling and debt-ridden health maintenance organisation, Ramsay was recognised as Florida’s entrepreneur of the year in 1993. By then, Ramsay Health Care Inc. was running 16 psychiatric hospitals across 12 states.

When the psychiatric hospital business slowed later in the decade, Ramsay Health Care demonstrated the kind of business savvy that would make its namesake so successful, rebranding in 1998 as Ramsay Youth Services (RYS), and pivoting in a new direction. A Miami Herald article described the company’s “new mission” as providing counselling, education and other programs for troubled or at-risk juveniles. Paul Ramsay’s Wikipedia page still calls Ramsay Youth Services “a charity for young people”. In fact, Ramsay Youth Services operated private prisons for children.

Private prisons had been steadily expanding across America, and Florida was a particularly appealing epicentre for Ramsay Youth Services’ new focus. One of the prisons run by RYS was the Florida Institute for Girls (FIG), which opened its doors in 2000 as the state’s first maximum security facility for female juvenile offenders, after winning a $5.2 million contract from the state. The Institute was considered somewhat revolutionary at the time, supposedly providing a second chance for girls who had been betrayed and damaged by the system.

But the FIG story quickly took a dark turn. In 2003, a Grand Jury investigation began investigating the Institute over inappropriate sexual contact, improper use of physical restraints and excessively long stays in isolation units. When first questioned by reporters, senior executives at RYS said they knew nothing about the investigation.

Underpinning the controversy was the fact that the Institute was being run on a skeleton staff. Guards had been hired with little qualifications (usually a high school diploma was enough), minimal vetting and on meagre wages of $7/hour. It was a repeat of the cost-cutting measures that had been used so controversially in Perth, and stood in stark contrast to the “Ramsay way”.

When the Grand Jury report was released, revealing several instances of sexual abuse at the Institute, RYS had been sold to another company. As a consequence of the investigation, Florida cancelled RYS’s successor’s contract to run the Institute, and in 2005 it was shut down for good. The scandal eventually cost two consecutive state Secretaries for the Department of Juvenile Justice their jobs.

But the scandal didn’t seem to touch RYS’s directors, several continents away. It’s unclear how much Paul Ramsay knew about what was happening at the Institute. Still, at the time when the crisis was at its peak, Ramsay was Chairman of RYS, while Peter Evans, a lifelong member of the billionaire’s small inner circle, served as a director, according to Ramsay Health Care’s annual reports.

Generosity, and a small media business

Back at home, Ramsay’s involvement in the business he built from scratch appeared to be much more intimate. His loyalty with his executive team intensified and he went to great lengths to look after staff. This created a culture that was almost paternalistic.

The bond he forged with people was intense, according to his business colleague and friend Graham Rich. “Most people that you come across within his companies would walk under a bus for Paul,” he told the SMH in 1995. “He is not one of those intensive, hands-on owners and manipulators of the business.”

Ramsay also built a media empire alongside his health one. Through the acquisition of regional television networks, he controlled what would eventually become Prime Media, an affiliation of the Seven Network. This investment made him a media mogul of sorts, and added even more powerful names to his already crowded Rolodex: Kerry Stokes, Gai Waterhouse and Paul Keating to name a few. Then just months before his death, he sold his 30% stake in the business, earning him nearly $100 million.

Ramsay was generous in death, leaving more than $400 million to his friends and family, turning some into instant millionaires. Michael Siddle was the biggest beneficiary, with his family bestowed cash, shares and property worth $200 million, including $25 million for each of his daughters. Ramsay’s business development director Sam Savchenko received $50 million and a fully furnished Circular Quay apartment, while his personal assistant Chris Gunn received $20 million.

Ramsay left $50 million each to his brother Peter and sister Anne. His old school, St Ignatius’ College Riverview, received $1 million. Even his gardener was made a millionaire, according to the will, leaked to the SMH.

But the majority of his life’s wealth went to the Ramsay Foundation — administered by Siddle, Evans and Clark. The trio have declared the Foundation will remain a long-term shareholder in the company, in accordance with the will.

Speaking at his funeral, Siddle said Ramsay was not one to let bad blood come between friends, with “Ram” preferring to iron out any “argy-bargy” he had with people over a glass of red wine. “The right way to do it, eh, Mr Stokes?” he said, with a nod to co-billionaire Kerry Stokes.

Most interesting.

The media in general is so busy obsessing about celebrities that tall poppy stories such as Ramsay’s fly under the radar. I am curious to know whether his business nous thrived under a mentor or if he had a natural propensity for sussing out opportunities.