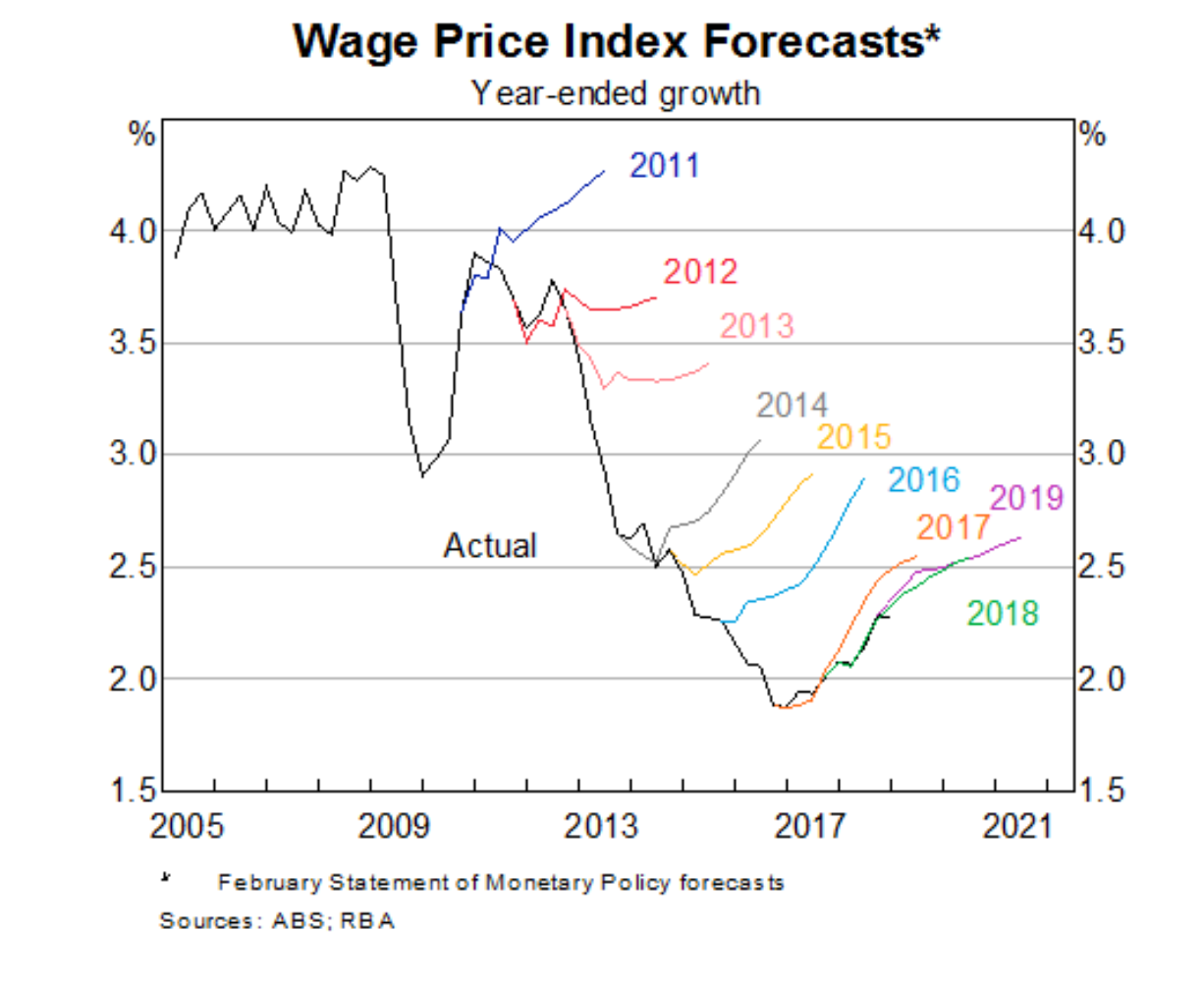

Last month the Reserve Bank of Australia dedicated its major annual conference to low wages growth. We all know it by now: the big problem in the Australian economy is a tremendous shortfall in wages growth. So, the RBA flew in experts from around the world to dissect the issue forensically.

Many hypotheses were put forward; too many, in fact. And the long summary of proceedings was this: we don’t have a clue what’s causing low wages growth.

That’s not a non-story. That’s a hell of a story. The implication here is as clear as it is terrifying: if we don’t know the cause of low wages growth, we are ill-equipped to address it.

How bad is this problem?

After years of wages lifting 4% annually on average, we’re stuck in a terrible rut. Wages go up by 2% now, if we’re lucky.

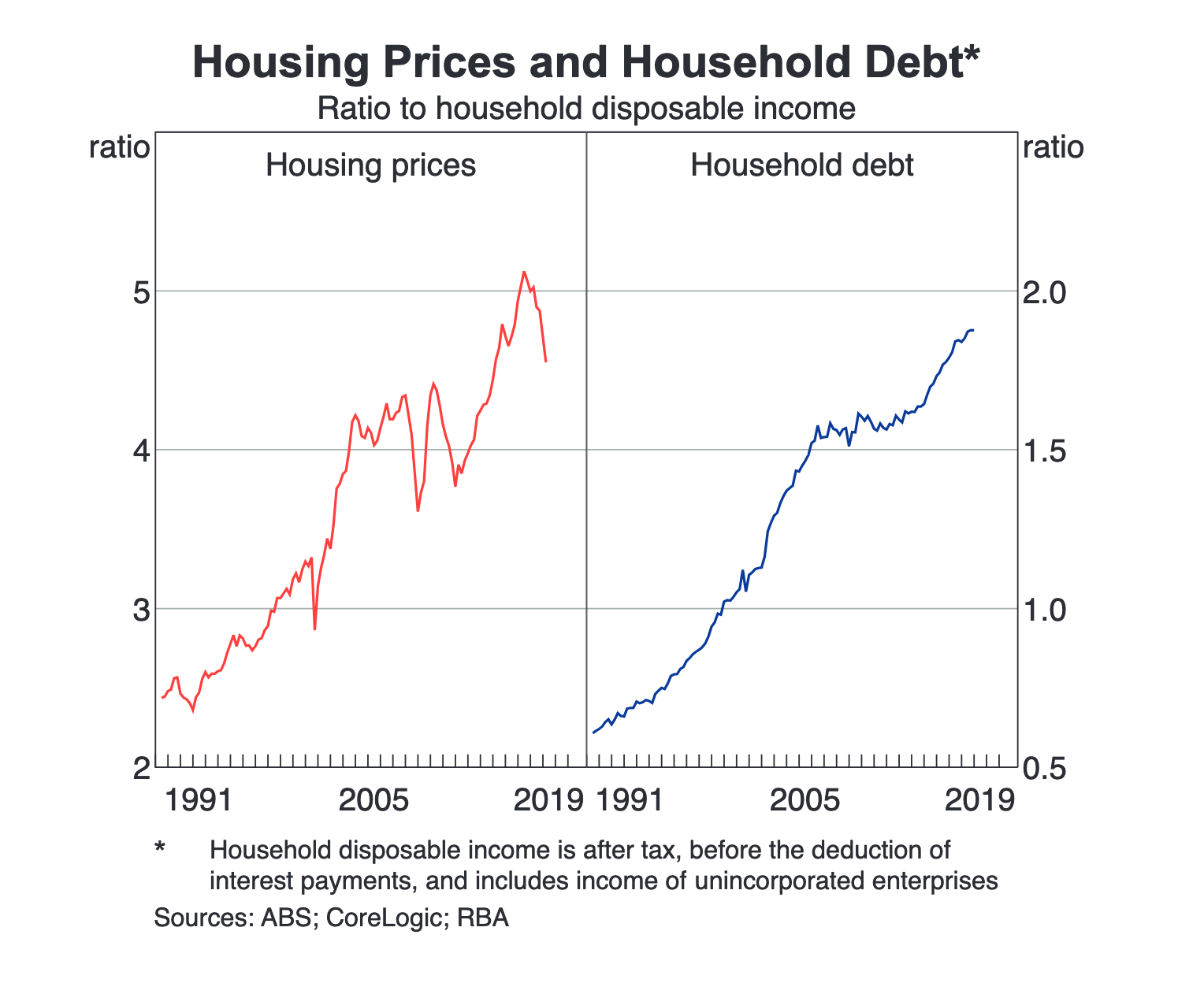

The only thing preventing negative inflation-adjusted wages growth in recent years is the fact inflation is also at record lows. Dismal wages growth is a big problem — Australia took on a record level of household debt in the past decade. Take a look at it:

Historically, debt has proved quite easy to pay off. Sums that seem large when borrowed grow less staggering each year as wages growth compounds. For example, a two-person household that borrows a spine-tingling $150,000 for a mortgage in 1990 might find themselves earning that much in a single year by 2010.

But such wage-inflation debt relief seems unlikely to arrive any time soon. Wages are growing very slowly in nominal terms, leaving us to deal with a very substantial household debt situation the hard way.

Wages growth also keeps Australians spending. Household consumption represents 57% of Australia’s GDP. If consumption stalls or sinks, the whole economy sinks or stalls with it. That would put people out of a job, and a negative feedback loop between lack of wages growth and the lack of consumption would turn into a vicious whirlpool draining the life from the economy.

The big shrug

Is this caused by a lack of demand in the economy? Poor productivity growth? Low inflationary expectations? Migration? Automation? All these may or may not be the answer, the RBA is unsure.

The wrap up from the conference contains this nugget of a sentence, which encapsulates the overarching uncertainty rather well:

As noted by John Simon, Head of Economic Research at the RBA, in his concluding statements, there is clearly not enough evidence to single out one cause “beyond reasonable doubt”; even on a “balance of probabilities” standard of proof it would be challenging.

It is possible we will unlock the mystery of low wages growth later, after it has ended. Alternatively we may never figure it out. Wage stagnation could be a side effect of a multiplicity of factors each subtracting a little from wages growth — none of them sufficient to be considered a major culprit.

While the answer is not in, the RBA thinks they can rule out a few suspects. Papers presented at the conference tended to suggest that declining trade union membership and the rise of the gig economy are unlikely to be the cause of declining wages. Of course, and in keeping with the overall theme of doubt and uncertainty, the conclusions of those papers were disputed.

One thing that is clear is that low wages growth is not a peculiarly Australian phenomenon. The UK and the US are also experiencing the kind of wages growth that gets called “tepid”, despite unemployment rates that are at record lows.

Can interest rates help?

The RBA would dearly love to spark wages growth in the Australian economy.

Several months ago the bank said the “natural” rate of unemployment was 4.5% and it would be necessary to reduce unemployment below that level to cause wages growth. It cut rates, which might make you hope it now expected unemployment to fall to that level.

However, following its most recent board meeting this week, RBA governor Philip Lowe suggested the unemployment rate would be above that key level for years to come.

“The unemployment rate is expected to decline over the next couple of years to around 5%,” said Lowe. “Wages growth remains subdued and there is little upward pressure at present, with strong labour demand being met by more supply.”

At this gloomy juncture the only hopeful thought to hold in mind is that uncertainty cuts both ways. The bank’s grim outlook could be unwarranted.

After all, it might be as wrong about wages growth on the way back up as it was on the way down.

I’d be interested to learn why stagnant wage levels is not at least partly due to low union membership + legislation weakening workers’ rights to take industrial action.

I agree. Especially as history suggests both that strong unions = strong industrial agitation = strong wages growth and that weak unions = weak industrial agitation.

Hmmm. I wonder where/how weak wages growth fits into that picture?

I agree totally with the two contributors who have posted comment so far.no unions, no wage rises, it’s very simple.however, as unions are demonised more every day, the anti-worker media are spreading the line that it is the unions who are the cause of the low wages, and not the solution to the problem.i know that if I try to bring the subject up all I get is,”Oh, I’m not interested in politics”.when this government finally succeeds and unions are no more, what will the average worker have to rely on for improvements to wages and conditions? We are fast going down the American road where 40 % of the workforce have been relegated to the position of helots and rely on food stamps and charity.to praphrase Bonhoffer,”First they came for the communists and I said nothing, because I was not a communist. Then they came for—–“.

Thank you for your first graph about wage rates and price index. Because the vertical axis goes all the way to zero, the absolute values of the quantities are displayed, allowing the reader to eyeball the curve to see the proportional changes. Indeed, wage rates growth drops to one third and the growth in the price index halves. Good material for thoughtful readers to study.

The next graph fails to go to zero. Consequently the casual reader infers that the housing prices have shot up tenfold and debt has gone up fourteen times. False! Unless your intention was to deceive, this is not what you want the reader to infer. I think you’ll agree that this graph was not prepared by ABS at all, but by professional illustrators. If you consider that professional illustrators’ main customers consist of salesman and axe grinders, it is almost inevitable that they will distort the data that they have been paid to display, with an honest intention to please a dishonest paymaster.

I urge any journalist to get the relevant data direct from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and graph it up yourself (from zero, etc), so that a thoughtful reader can study the graph to follow your argument and make further inferences from it.

You left us hanging on the vital explanation of who these supposed experts flown in were. Birds of a feather would be my guess but perhaps you could elucidate.

Wages are still about the age old class struggle between buyer and seller no matter what post modern post truth varnish you care to apply.

Strikes are now all but illegal and any industrial action must be “protected”. Maybe younger workers don’t register the insult but I sure do.

FFS I have never seen such a glaring example of the ‘expert problem’ (see Taleb). It is so bloody obvious that these useless boffins cannot see it under their noses: The power of labour to negotiate with capital has been deliberately suppressed. The undeclared policy of this bunch of muppets in government is to maintain, not reduce, a large pool of unemployed and under-employed. Management of Australian companies is substandard, exemplified by the appalling rate of R&D, hence the shit productivity growth.

The RBA did not need this bunch of clueless ‘experts’. They only needed to ask Wayne Swan, Richard Dennis etc.

It really, rilly is that simple.