In late 2017 Peter Dutton introduced a small, seemingly trivial change to the bureaucracy governing companies seeking to sponsor foreign workers, on what were formerly 457 visas. He proposed that, where previously sponsors contributed 1-2% of company payroll to train people to fill a skills gap, businesses would now simply give Home Affairs that money.

The plan was that over four years, money raised through this scheme would then make up $1.2 billion of the Department of Education’s $1.5 billion Skilling Australians Fund (SAF). It was known as the SAF levy.

It seemed like a win-win: companies could still hire international workers, the federal government would collect the money and distribute through existing state training schemes, and Australians could develop the skills we are, for whatever reason, currently lacking.

The most potent change, however, would come in the fine print. The SAF levy paid by businesses to sponsor a foreign worker can range between $1200 to $7200 depending on company turnover, visa type and length of stay, and must be paid at the point of nomination. But in the case of refused nominations, the fee cannot be refunded. And once rejected a second application and a second fee is required.

Home Affairs, in effect, gave itself a licence to print money; it could charge fees at its discretion, while also being in control of who does and doesn’t get approval to work in our country.

This bureaucratic trick allowed the department to rake in more than $7 million from rejected sponsorship nominations — and that was only the first four months of the levy being in place. However, linking an apprenticeship funding scheme to a migration levy raised immediate flags with states.

After a year of negotiation, Queensland and Victoria ultimately refused to sign on to the scheme, largely out of fears of funding certainty. This robbed the SAF of vital support.

To add insult to injury, these fears have played out: the SAF, as predicted, failed to meet its funding projections. Home Affairs declared in March that the fund had received a total $90.3 million from the levy between August 12 2018 to January 31 2019, significantly short of its first year target of $243.4 million and $1.2 billion over the forward estimates.

Strangled by red tape

According to an FOI lodged by an agent at the Migration Institute of Australia (MIA), Temporary Skill Shortage (TSS) visas were refused or withdrawn 2,324 times between August 12 to December 31, 2018. With refunds overwhelmingly hard to come by, MIA’s president John Hourigan believes “the vast majority of that would not have been refunded, and businesses were then required to pay the SAF again”.

“Some of the decisions to refuse were just silly reasons a simple phone call with the department could have resolved,” Hourigan explained, adding that the upfront nature of the levy means that even successful nominations can become “fees for no service” if an applicant withdraws. “If you’ve lodged the application and someone dies, and that actually has happened: no refund.”

A subsequent FOI submitted by INQ found total rejections of TSS visas grew to just 2,954 by June 3, 2019. This drastic decrease in refusals suggests either: a) fewer applications; b) applicants are making fewer errors; c) a combination of the two; or d) another factor entirely.

Applicants for TSS visas can be remarkably diverse, with the top four primary occupations granted visas in 2018 being:

- Developer programmers

- ICT business analysts

- University lecturers

- Cooks.

The levy applies equally across all occupations, but does vary according to length of stay and business size.

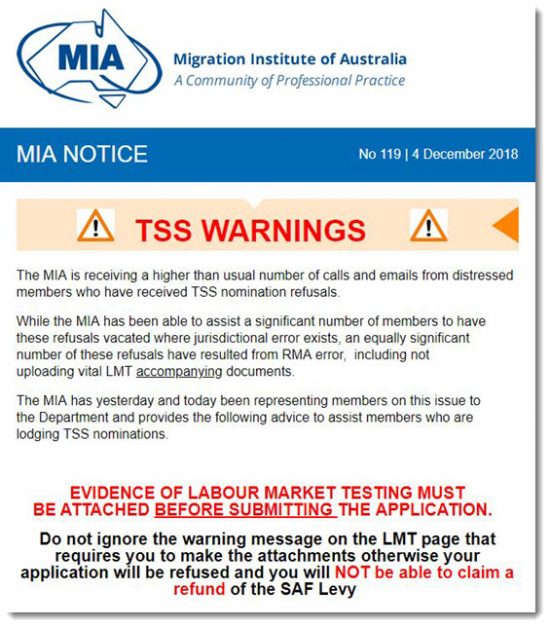

Just two months into the scheme, the MIA had issued internal warnings citing calls and emails from migration agents looking after Australian businesses, over increased TSS refusals. The refusals were largely born over confusion about new, stricter rules governing the advertisement of job positions known as labour market testing (LMT) — a process of demonstrating local applicants were either not qualified or interested in the role and demonstrating that there was no one locally to fill them.

Mired with the new levy provisions and increasingly less tolerant case officers — Hourigan argued in a Senate inquiry that the SAF levy’s introduction saw visa processing officers move away from issuing “requests for further information and refused TSS nominations instead of seeking clarification on matters or asking for missing documentation” — the new LMT rules led directly to some of the most extreme examples of lost money.

In a June briefing note to Immigration Minister David Coleman, the MIA notes that an accredited government agency lodged eight TSS nominations and visa applications for healthcare professionals, but all were rejected in part because job advertisements placed on Seek were considered inadmissible. One of the requirements for LMT is that you do more than place a job ad on your own company website. In this case, the Seek ads linked back to the company website (as most Seek job ads generally do) and therefore, on a technicality, weren’t accepted.

“Conservatively, this is a potential $60,000 cash grab by the government from a publicly owned government agency,” the MIA reported.

While limited, refunds for the SAF levy are possible for departmental mistakes, visa applications rejected on either health or character grounds, rejected concurrent business sponsorship fees, or when workers either do not arrive in Australia after visas are granted or cease employment within 12 months. Religious bodies are also exempt from the fee entirely, a point Home Affairs would not clarify to INQ.

It’s currently unknown how many people have been successful in obtaining these refunds, only that, according to agents blowing off steam in online forums, time constraints have meant that some businesses have opted to simply start from scratch and pay the levy again, rather than spend months explaining that a signature could be found on a separate PDF.

Hourigan, a Canberra-based migration agent, has consistently fought against the levy. At a Senate inquiry into visas and skills shortages in March, he was joined by the Law Council of Australia and the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI), which also voiced concerns.

Home Affairs told the inquiry that payment of the levy “at the time of lodgement of a nomination, seeks to minimise the administrative cost to sponsors and the Department of Home Affairs, by removing the need to go back to the sponsor for collection of any payable fees during the assessment process”.

However, Hourigan points out that collecting fees after a case officer has approved initial documents is already common practice amongst other kinds of visa applications. When pressed on why refunds weren’t available to all failed nominations, the department told INQ:

“Prospective sponsors should consider the requirements, including costs, when deciding to lodge an application seeking to access overseas workers [and] are encouraged to undertake due diligence before nominating overseas workers (in effort to reduce risk of refused nominations or visa applications).”

The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industries director of employment education and training Jenny Lambert is candid about why she thinks the government is unwilling to issue refunds.

“We can only assume to maximise the revenue collection,” she said. “We achieved some success in having the levy refunded in some circumstances (which was evident in the federal budget 2018 as a cost to budget of changing the policy), but those circumstances are too narrow.”

The Skilling Australians Fund flop

The SAF is a Commonwealth initiative that gives money to existing state training bodies, who were then expected to meet the funding provided. However, state Labor governments were critical of tying funding for apprenticeships and training to a fee paid by business, as opposed to traditional government revenue.

Federal Labor was similarly critical, slamming the shift to make a skilled worker levy almost the sole source of Commonwealth revenue for skills development as “astounding” even while supporting, and planning to increase, the levy itself.

Western Australia joined the scheme after initial reluctance and South Australia elected a Coalition state government more supportive of the plan, but Queensland and Victoria refused to take part. This meant that even if the SAF received its projected funding, the federal government would have found itself with $463 million with nowhere to go.

Their rejection, and unofficially the levy shortfall, saw total funding for the SAF downgraded from $1.2 billion to $573 million in the April budget, while money allocated for Queensland and Victoria was redirected to another new $525 million skills package, this one aimed directly at the VET sector.

While the government flaunted their “Delivering Skills for Today and Tomorrow” package at budget time, redirecting $400 million initially meant for the states and simultaneously gutting the SAF by at least $649 million saw even beneficiaries hit out.

TAFE Directors Australia chief executive Craig Robertson told the AFR in April that funding 75% of the scheme with SAF money amounted to “robbing Peter to pay Paul”, and warned it could compromise state and territory governments’ ability to work with employers.

Considering the SAF raised just $90.3 million over more than five months with an annual target of $243.4 million, INQ approached NSW, WA and SA education ministers to find out if any of them had been short-changed, or expected to be. Western Australia’s Education and Training Minister Sue Ellery, at least, assures us they have not.

“Western Australia chose to sign up for $110 million,” Ellery said. “The recent federal budget reflects a forward estimates total of $110 million for WA, which means there should be no change to the total funding negotiated with the Commonwealth under the national partnership.”

With the SAF levy only a year old, it’s perhaps too soon to determine what impact the funding shortfall has had. An education spokesperson tells INQ that the government provided almost $150 million to the six state and territory signatories in 2018-19. It assigned almost $160 million through the 2019-20 budget.

Pointedly, the department also notes that “since the Skilling Australians Fund was established, the government has been clear that the funding available through the program is subject to revenue collected through the levy”. Essentially, the government has given itself a get-out-of-jail-free card should its own program fall short of what was promised.

This is handy considering the SAF has shown to be underfunded, rejected by various states and now gutted in the last budget.

The best that people like Hourigan can hope for is some expansion of the refund provisions come budget time.

“Now that will be a very long and slow process,” he said, “and I think the Treasurer and the Finance Minister probably will be reluctant to actually give up a great deal of money given that they are not achieving the actual revenue from it that they thought they’d get.”

So the SAF is actually SFA

So whose cunning plan was it?

Sorry, but it’s hard to imagine Spud coming up with something like that.

And no can be bothered to call it corruption, falling back of the old faithful, incompetence.