The addiction of Australia’s universities — particularly its major ones — to revenue from foreign students is creating an array of problems that make it unsustainable for the economy, for our security, for taxpayers and for universities themselves.

A new report from the Centre for Independent Studies — that’s like the Institute of Public Affairs, but with credibility — strongly makes the case that universities are now at serious risk from any shock to the flow of Chinese students into Australian universities. The report, by Salvatore Babones, details the extraordinary dependence of major universities on foreign students, the ways in which academic standards have been systematically lowered to accommodate it, and the threat that such dependence poses to those institutions.

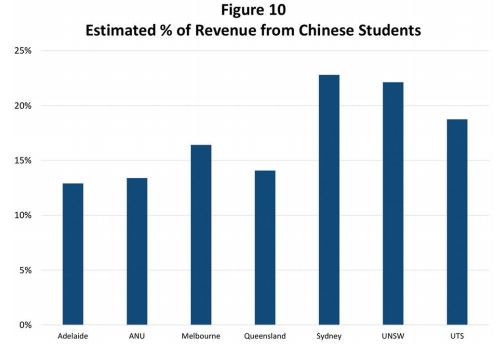

Australia is, per capita, easily the world leader in educating foreign students: our number of foreign students per capita is more than twice that of the second-highest country, the UK. International students make up more than 25% of all enrolments at Australian universities, but ten universities, including most of the major institutions, have between 35-40% of enrolments from overseas. They are particularly dependent on Chinese students — at more than 10% of all enrolments, Chinese students form a much higher level of enrolments here than anywhere else. The specific location of our addiction is business schools, where at five major universities more than 40% — and in two cases closer to 70% — of enrolments are of foreign students.

Babones demonstrates how, to facilitate this, major institutions not merely waive basic English language requirements but actually turn the lack of English language skills on the part of foreign students into a money-making opportunity. They charge tens of thousands of dollars for enrolment in English language courses offered by university-linked, private providers that mean students are never required to meet enrolment standards. They have also lowered their academic standards: the University of Sydney accepts Chinese students with low Chinese domestic examination scores, using the same scores at middling regional universities elsewhere.

Babones argues against the claim put forward by some of us, and by universities themselves, that this dependence has been driven by lack of government funding. In fact, he shows, universities have dramatically increased their reliance on foreign students at a time when student-related government funding was increasing — a view backed by Grattan Institute’s Andrew Norton and Ittima Cherastidtham last year, although they pointed out research funding has fallen in recent years. Universities have dramatically increased revenue over the last decade, and generated sizeable profits during that period.

This heavy dependence on Chinese students, Babones argues, means our biggest institutions are exposed to major financial risk via either an economic or political shock that significantly reduces the number of Chinese students coming to Australia.

He notes their efforts to diversify by trying to source students from India, but argues that India cannot even begin to match the revenue available from Chinese students — and universities would have to further lower their standards to attract it. As a result:

At these levels of exposure, even small percentage declines in Chinese student numbers could induce significant financial hardship as universities struggle to meet the fixed costs of infrastructure and permanent staff salaries in the midst of a revenue shortfall. Large percentage declines could be catastrophic.

The risks identified by Babones are only one sub-set of the problems created by our dependence on foreign students. The nearly-five hundred thousand foreign students currently in Australia provide a rich resource for employers to exploit, with wage theft and other forms of exploitation rampant among industries that rely on visa holders, such as hospitality and retail. This in turn provides downward pressure on wages for others workers, adding to wage stagnation, and harms the image of Australia in the eyes of exploited students and their families.

The growth in foreign student numbers also makes a mockery of government claims that it is reducing permanent migration to reduce pressure on infrastructure in Sydney and Melbourne: instead, the rapid rise in student numbers has added to congestion on key transport routes and put further pressure on urban housing markets. The presence of large numbers of Chinese students, and the thirst of universities for foreign funding, has also provided a mechanism for the Chinese regime to exert its malignant influence in Australia, both directly via Confucius Institutes and other platforms for propaganda and academic intimidation, and via intimidation and surveillance of Chinese students in Australia — especially those tempted to take advantage of university traditions like free speech and protest.

It’s not just universities that have made a Faustian bargain — far greater than any other higher education sector around the world — in pursuing revenue from foreign students. Business and governments have also benefited as education became our third highest “export”. There’s no managing this array of problems: the only solution is a reduction in foreign student numbers and ending our universities’ addiction to the revenue generated by them.

The really stupid thing is that we mostly getting the 2nd & 3rd tier students. The smartest stay in China.

No, no, all that matters is their capacity to pay the fees. Students completely lacking a brain are equally acceptable given their boost to university executive remuneration.

“… major institutions not merely waive basic English language requirements but actually turn the lack of English language skills on the part of foreign students into a money-making opportunity.”

These are not the only language related problems. Many business and finance studies courses used to require students to read and demonstrate knowledge of relevant legal cases. Reading legal decisions is not a simple matter and few non English speaking students have the necessary language skills to understand the importance of any decision. So the requirements were removed from the courses.

Well, Bernard, you have got some of the problems caused by over-reliance on foreign students. For Universities, the pressure to lower standards is huge. As you point out, a source of illegal cheap labour undermines living standards for Australian workers.

To say though that CIS has credibility is a bit much. Of course funding has increased but it has not increased at the rate Universities need to support research time for the large number of research active academic staff, who do not win decreasing research grants. The neo-liberal response, of course, is that such research time be taken away. They don’t realise that, if that happens, students won’t generally be taught by staff that are at the cutting edge of new work in their fields.

This will reduce the international standing of Australia’s leading universities and thus tend to dry up the flow of overseas students, at least those who are not simply looking for residency.

The problem has its origin in the neo-liberal belief that endless productivity improvements are possible in all fields, whereas they are possible only in some, which should be obvious to anyone not in the grip of economic ideology.

Funding growth should have been greater. That is the only way to avoid “addiction” to having foreign students.

Then, as part of the manifestation of the dominant American influence in our institutions, we have the obligatory bit of China bashing, into which Bernard joins with some enthusiasm, although he should know that Chinese influence is very small compared with US influence and that there a US push to have Australia line up with the US confrontation of China, when our own national interest is not to get involved.

All foreign students should be free to speak freely in favour of what they think is right. It will be useful for them to see that the Australian government’s restrictions on public discussion don’t extend to shutting up foreign students. We, of course, have to judge what anyone says in public and make up our own mind on issues.

It is a pity that the 5 eyes intelligence system we belong to has only 4 brains. It is a pity too that US influence in Australia is so established and so strong that we might be led by the nose to joint the US attempt to block China’s technological progress.

Australia should disagree with China’s claim on the South China Sea and on other issues but we need not go all the way with Trump DJ.

I agree with most of what you say Ian, however the winning of research grants tends to mean the academic stops teaching for the terms of the grant, and farms that out to casual academics.

The only way research active academics do teaching is when they don’t win research grants, sort of a perverse outcomes situation.

Thankyou for naming the neoliberal gorilla in the room – something the (?’credible’) CIS is congenitally unable to recognise.

Wow! Who could possibly have foreseen a decade or so ago that transforming our universities from educational institutions into profit centres might have adverse repercussions? I mean, it’s not like strategies based on rampant greed ever caused problems.

I blame John Dawkins.

Ya but also linking education to earning points needed for permanent residency has also turned up the demand side…extra points if you study in regional areas or SA.

>Babones argues against the claim put forward by some of us, and by universities themselves, that this dependence has been driven by lack of government funding. In fact, he shows, universities have dramatically increased their reliance on foreign students at a time when student-related government funding was increasing — a view backed by Grattan Institute’s Andrew Norton and Ittima Cherastidtham last year, although they pointed out research funding has fallen in recent years.

To coin a phrase: ‘Well they would say that, wouldn’t they’. Not sure how we allowed the funding debates in higher education to be run by these various neo-liberals, who have never believed in any basic way in our universities as public insitutions deserving of major investment and support. This is all chickens coming home to roost – after Howard government realised they could continue to cut funding throughout late 1990s and 2000s and to have this replaced with international student enrolments, all promoted with the carrot of permanent residence.

No doubt the next brainwave from the free-market fanatics – after it is now accepted that overreliance on internationals students is a disaster – is renwewed calls for privatisation of the sector. And this would be in the face of the recent catastrophe in the VET sector, when the privatising fanstasies were briefly given free rein.

PS Why BK accepting the funding line so readily? His contortions around the virtues and vices of neo-liberal paradigm a marvel indeed.

The issue of Chinese student numbers at Australian tertiary institutions has clearly become more extreme lately, but it was a factor even back as far as far as the 1980’s. At that time I was doing engineering at UTS, where students from all faculties shared a common, fairly large computing centre. My cohort would travel in to UTS at odd hours over the weekend or go after night lectures (we were largely mature age, part-timers) to hop on a machine for half an hour to see if our bridge beams would work, or whatever. No luck, every machine was permanently surrounded by a scrum of 6 or more mostly Chinese students who appeared to live in the computer centre! The rumour was that they were all running family businesses from there; if not the case load from the Faculty of Business must have been horrific! Gaudeamus igitur!