Is Australia dependent on China? Or is China dependent on Australia? At a time of increased geopolitical tension, the growing trade relationship between the two countries is now a burning political issue.

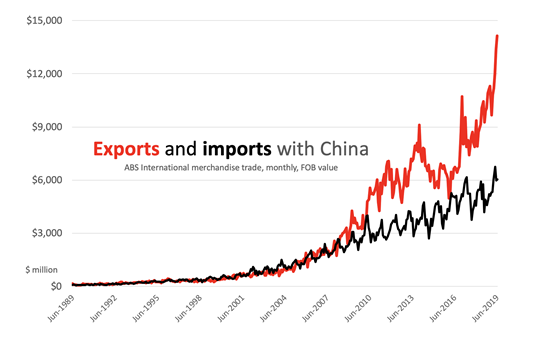

Australia’s iron ore exports to China have always been strong but, with the trade war between the US and China turning red-hot, they have strengthened further. The trade imbalance between Australia and China is now at a record high.

The shifting narrative

This development led to a fascinating story in The Australian Financial Review last week that upended a popular trope: it is China which is reliant on Australia, argued author Angus Grigg. He claimed the steady northward stream of boatloads of iron ore and coal were “crimping Beijing’s ability to penalise Canberra for its tougher stance on national security issues”.

Australia is now the major source of Chinese iron ore imports, providing 74% of that country’s supply during June. Iron ore remains central to the steel-making that drives China’s infrastructure-led economic growth.

It is doubtless true that China depends on us — we control a mighty share of iron ore supply globally. However it’s not as if we are giving away iron ore for free. They pay for it, and handsomely. This year iron ore prices leapt back over $100/tonne — levels not seen since the heady days of the mining boom.

Seeing trade through a lens of winners and losers, power and weakness, is a Donald Trump move. Trade is an inherently interdependent relationship. Both sides gain from trade. We forget that at our peril. And focusing on a single commodity in which Australia has some market power may miss the bigger picture.

The iron ore narrative could just as easily be flipped: after all, Australia’s giant mining industry depends heavily on a single major customer. Goldman Sachs issued a research note this week showing that our economic growth would be halved if China trimmed its imports from Australia.

The narrative of Australian dependence on China was also advanced in a different recent media storm about higher education. Australia’s universities are highly dependent on China, and a downturn in Chinese students, the pieces argued, would be “catastrophic”.

All of these articles are a disappointment for those who abhor Trump’s trade war. The use of trade as a political weapon is now coming back with a vengeance, and the old rules-based trading order is looking wobbly.

That rules-based trading order — carefully tended since the end of World War II — has been vital to Australia’s growth, and arguably to its security. The golden arches theory of global conflict, which claims two countries with a McDonald’s have never gone to war (the theory can be defended only if you rule out various small wars, skirmishes and NATO bombings), illustrates the idea that once two nations’ interests are sufficiently intermingled, conflict becomes unimaginable.

But the power of the World Trade Organisation is in decline as tariffs come back and the fragile consensus for free and non-discriminatory trade crumbles.

The opposite of free trade is a mercantilist approach that exploits power, favours friends, pays little heed to the will of the market and is historically terrible for mutual economic growth.

China and unavoidable politics

Of course, trade has never been without a political dimension. We keep foreign affairs and trade in one department for a reason. And, in dealing with China, the link from the economic to the political is even tighter.

Communist Party control of state-owned enterprises means the distinction between trade and everything else is never that clean. Banning Huawei from Australia’s 5G network is a great example of how muddy the situation can get. Where is the line between China’s economic interest and its political ambitions?

The AFR story mentioned above emerged in the aftermath of extremely strong comments by Liberal backbencher Andrew Hastie over how Australia should work to control the threat of China. With China appearing set to roll armed police into Hong Kong, that threat has never looked more concrete nor more immediate.

So, can our trade relationships and the wealth they have created survive the threat of a rising China?

The pessimistic conclusion that could be drawn is that rather than supporting decades of global peace, the rules-based trading order was merely facilitated by it. We lived through a dreamlike period of growing trade and growing wealth because there was no major non-Western threat. Between the US, Europe and a demilitarised Japan, consensus allowed trade to be decoupled from great power politics.

In this pessimistic view, the rise of China changes that — and expecting free trade to continue unabated denies the importance of major geopolitical powers in world history.

The more optimistic conclusion would be to look at the role of Donald Trump in setting the narrative by scapegoating China. His insistence that America’s trade imbalance with China is a major political issue is echoed in recent media reports about Australia’s trade imbalances with China.

With a different president in the White House, a different story could be told — one that returns trade to its rightful role in the background.

What do you think of the current narrative on Australian trade? Send your comments to boss@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name.

I honestly don’t understand how arrogant you can be to announce those figures and not realise how fucked you are. Like imagine being in Mugal official in around 1740 and thinking “we have figures that show that our calico and spice account for a huge part of the Britians imports, so all we need to do is tell the East India Company to play by the rules after all they need us a lot more than we need them.” now imagine instead of talking about a 3rd rate pirate island on the other side of the world your talking about the country that for almost all human history has been the paramount regional (if not global) power.

Seriously ask any peripheral state how the supplier of a economically crucial commodity to a much larger power worked out for them…

We are so fucked.

…ssshhh…!

It’s rather like surfing, one only pretends to control the ride.

Ah yes, “free” trade. “Free” trade snake-oil merchants promote an ideology supposedly promoting individualism, free enterprise, lowered taxes, deregulated economies and labour markets, and small government, the idealisation of “free” (actually meaning unregulated) markets, a servile State, and privileges the profit-seeking sector at the expense of public interests and welfare.

The World Inequality Report 2018 – co-authored by the French economist Thomas Piketty – showed that between 1980 and 2016 the poorest 50% of humanity only captured 12 cents in every dollar of global income growth. By contrast, the top 1% captured 27 cents of every dollar.

Why should we the 99% here care about “free” trade, when 90% of the profits are pocketed by the corporate sector?

“Free” trade has never been explicitly intended to benefit ordinary people; it was and is always done to expand and enrich the capitalist class. Today’s ever greater polarisation of global wealth and incomes is exactly the result intended by the global capitalist class when it revitalised its class warfare against us the 99% from the early 1980s.

As Marx so rightly suggested, government is never neutral. Governments are rarely a tool for social good, instead are the mechanism owned by the ruling class through which it further enriches itself. Enforcing plunder has for centuries involved a remarkable range of viciously anti-social policies.

As is highlighted by nostalgia for the American Camelot, the long post war boom was working very well for the masses but not working so well for the big corporations. So from about 1980, transnational companies allied with national ruling classes promoted an ideological framework that would achieve that end through its network of politicians, businesspeople, academics, the media, and other agents of influence. Globalisation and financial deregulation globally (here, by Hawke Labor from 1983) were added to the mythology of “free” trade to further enrich the rich by impoverishing the rest.

So today, eight people have the same wealth as the poorest half of the world’s population. That attracts less media and political attention than the small group of homeless camped in Martin Place, to which decision-makers (with the honourable exception of Sydney Lord Mayor Clover Moore) reacted with the customary weapons of the ruling class – threats, further oppressive laws, and the police.

The average working Josephine sees very little advantage from free trade when weighed against the transfer of jobs to the cheapest world labour markets. The is very little to cheer about when you look at the smoking ruins of Australia manufacturing sector.

So, it was a ‘rules-based trading order’ since WW2 whereby ‘the US, Europe and a demilitarised Japan, . . . . allowed trade to be decoupled from great power politics’? Really? And what and whose rules would they be?

So Vietnam, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, Israel-Palestine and a host of other power-plays at the point of a gun had nothing to do with economic imperialism? And the protectionist rules were OK for all the Western countries to develop their huge capital stock, but were suddenly changed to create the ‘level playing field’ that allowed these developed nations to trade ‘freely’ with the developing nations – a bit like letting the Year 12’s play rugby on a level playing field with the Year 1’s.