Australian governments have always been fond of talking up our Asian “neighbours”, “old friends”, “good friends”. But their track record of walking the talk is frankly embarrassing. At the highest level, Canberra has all but ignored its south-east and south Asian neighbours — except Indonesia, Singapore and India — for decades and, in some cases, 50 years or more.

This represents a potentially significant problem for Australia, especially strategically, given the US-Australia-Japan alliance’s chief rival China — as well as other regional mid-sized powers like Japan and South Korea — has taken the time to be neighbourly and friendly. China’s leader Xi Jinping and his No. 2 Li Keqiang are regular visitors to the capitals of even mid-sized countries in the Indo-Pacific region.

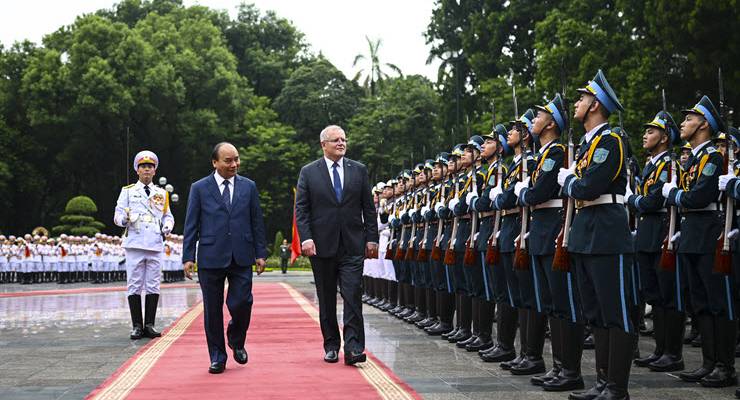

Australia’s shocking track record was inadvertently underscored by Scott Morrison’s surprise bilateral visit to Vietnam last week — the first by an Australian PM in 25 years. The last such visit was by Paul Keating was in 1994, the PM whose foresight on the importance of Asian countries being Australia’s friends and neighbours, not just transactional trading partners, has been unmatched since.

It’s not just Vietnam, a country that has clearly been a rising south-east Asian power economically and strategically for the past decade. The same treatment has been meted out to pretty much every other one of our much ballyhooed, publicly praised friends in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) — and further west, as well. ASEAN collectively is Australia’s second-largest trading partner, after China.

Thailand, the second-biggest ASEAN economy after Indonesia, has not received a standalone prime ministerial visit since 1998, when John Howard visited. This is despite Thailand being Australia’s 1oth-largest trading partner (it now makes more cars for Australia than any other country) and the second-most popular Asian holiday destination for Australians after Indonesia (driven by Bali).

The Philippines, which ranks as the No. 4 ASEAN economy, has likewise not been graced by an Australian PM visit outside the summit season for 16 years, when John Howard visited in 2003.

Malaysia, ASEAN’s No. 3 economy and Australia’s No. 11 trading partner, has fared quite a bit better, with Tony Abbott making a visit in August 2014, but this was an outlier and a lightening visit only due to the missing airliner MH17, which Australia had been searching for.

The smaller countries in the region have been basically ignored and forgotten. Myanmar has not had a standalone visit by an Australian PM since Gough Whitlam visited in 1974. For Laos it was also Whitlam in 1975, and for Cambodia it was Paul Keating, way back in 1992.

Even Timor-Leste — a country that Australia helped to gain its freedom from its Indonesia between 1999-2002 — has been ignored by prime ministers since Kevin Rudd visited in 2008, no doubt embarrassed by Australia’s now torn-up treaty, thanks to the UN’s Permanent Arbitration Court. The 2004 treaty robbed the tiny nation of undersea oil reserves and was later followed in 2012 by allegations the Howard government spied on the Timorese cabinet office during treaty negotiations. Scott Morrison will visit Dili this week to ratify a new treaty that gives Timor-Leste a greater share of oil and gas revenues.

Yes, the summits — ASEAN, the East Asia Summit and the Asia Pacific Economic Co-operation — present an opportunity to see other leaders. But everyone there is pretty much angling for the big guys — US, China and Japan — and trying to grab a photo op with them. The bilaterals are pushed to the sidelines, are rushed, and only a handful of other leaders can be met. Plus, summit visitors tend not to see much of the country they are in beyond the airports, hotels and function centres — and maybe a quick spin around in a bus.

Australia’s former ambassador to China Geoff Raby, who held the job from 2007-2011 used to insist visiting cabinet ministers take a trip somewhere apart from Beijing or Shanghai. It’s something German Chancellor Angela Merkel has been in the habit of doing as well.

Looking at the sorry list of neglect, undoing so much far-sighted work by Gough Whitlam and Paul Keating in particular, there is both an enormous amount of work to do and a sense that the obsession with China — now, as it was always going to, unravelling before our eyes — has come at a mighty cost for our ties with countries that, despite it all, still value us more than China.

“Australia’s shocking track record was inadvertently underscored by Scott Morrison’s surprise bilateral visit to Vietnam last week..”

I deplored Australia’s involvement in the war in Viet Nam and, as part of a personal expiation, after I retired I went to VN as an AusAID volunteer and worked as an English teacher for almost a decade.

Among PM Abbott’s first actions in 2013 was the closure of AusAID, the assets of which were systematically stripped out by the department of Foreign Affairs led by minister Bishop. It all went – scholarship programs, capacity building, language support, friendship links and ties, understanding of the culture of neighbouring countries – with the failure to recognise the value of so-called “soft diplomacy” being breath taking.

Now we do trade, not aid. But the teaching of Asian languages in Australian schools has declined so the traders and other dealers must rely on the English of the Asian peoples they are meeting with.

Stupid fella, my country.

I grew up in Canada so never faced the prospect of being conscripted, but in late 1992 I spent nearly two months in North Vietnam, based in Hanoi. I got to know a number of people like yourself, Americans in this case, who sought personal atonement for what their country had done to Vietnam. One was Barbara Cohen, a US Army psychiatrist during the war, who lived in Hanoi and wrote books about the country’s history and culture. Then there was big Jim. He had been a helicopter pilot during the war, and was living in Hanoi trying to set up a helicopter charter business by way of personal atonement. During one conversation he went livid and opined that “Nixon and Kissinger should have been hung back-to-back.” Then at the airport on the way home I met a group of American ladies in their 60’s who technically should not have been there as their government was sanctioning Vietnam. I asked one why she was there. She replied “I’m here because my government doesn’t want me to be here.” Pity there aren’t more like her.

Too long looking over their heads to the US and Europe …… wouldn’t have gone unnoticed.

Most of the countries named in the article have populations similar to or somewhat greater than Australia. Since they are all developing fast, they are destined to join Australia as middleweight nations in the United Nations. We share a common future, and are more likely to look to our region than the more global powers, China and India.

I work at a university in Bangkok that was a provincial backwater when I got a job here nearly 20 years ago. With the rapid application of new technologies, it’s quite clear that many sectors of Asian economies are leapfrogging Australia. My university now produces fantastic graduates in many fields. Now it is Australia that is starting to look like a provincial backwater.

Oh, don’t worry! The University of Queensland has covered itself in “glory” lately.

Firstly, its facial recognition technology was used to identify students taking part in the defense of Hong Kong’s political independence; whereby the student’s parents were contacted by police in the early hours of the morning.

Secondly; it has decided to partner with ” Ramsay Center” in producing IPA clones, or as someone called it, spaghetti BA’s in parts of western culture that Tony Abbott and John Howard find important.

Funnily enough, the only other University taking the money is the University of Woolongong. I am sure it will do wonders for its reputation on the world stage.

Bangkok University sounds like a far more prestigious and civilized place to be.

An arrogant patronising sort of “diplomacy” no better expressed than how “we” treated East Timor, in 1975 (sold into Indonesian bondage) and then Howard, Bunty “Nation Wrecker” Downer et al in the buggery of the government – to profit Woodside, a major donor to the Limited News Party?