On one unremarkable day in April this year, just over a third of news stories were about issues likely to impact young people, such as policies to address climate change, school teacher training, the impact of automation on future employment and proposed social media regulation.

Our snapshot study analysed the television and newspaper news in Australia on April 1, 2019. And our aim was to critique how young Australians aged four to 18 were included and represented in these traditional news forms that remain influential and popular, despite the rise of social media.

In total, we analysed 276 news stories across eight national, state and regional newspapers and four national and state television news bulletins.

Of all the news stories we examined, only 11% included the views or experiences of young people. Usually, their inclusion was via adult mediators like parents, police and experts. Just 1% of news stories directly quoted a young person.

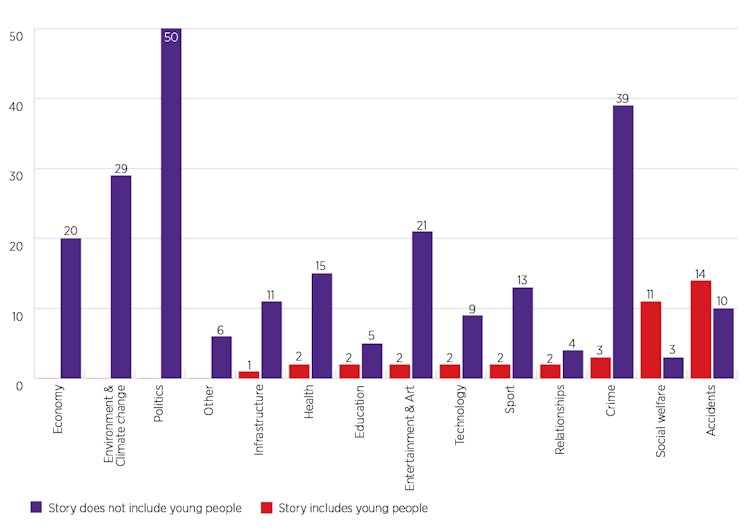

When young people were included in the news, we found it was most likely related to accidents and social welfare. They were absent from stories about the economy, politics, the environment and climate change.

Young people used as visual props

We also found young people were ten times more likely to be seen rather than heard in the news.

Of the news stories we analysed that day, 11% included a photograph or video footage of a young person or young people. Television news included images of young people almost twice as often as newspapers.

However, our analysis of these images finds young people are usually only peripherally included in the substance of the story, often acting as visual props to introduce colour or emotion, rather than being an integral part of the story itself.

In this way, young Australians are not being given opportunities to speak about themselves and their experiences, with journalists not consulting them or taking them seriously.

The Australian news media provide an important lens through which we see ourselves and our nation: they both reflect and influence public discourse and priorities. So young people should be meaningfully included in the news to ensure we are all better informed of their views and experiences.

A trust crisis affecting the future of news

We’ve been hearing a great deal about the future of news media in recent years. Usually these public conversations focus on how news organisations survive in the digital age; the role of whistleblowers and journalists in a global news environment; and the issue of so-called fake news and its impact on democracy.

These issues are all urgent and complex. Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that they have been the focus of our efforts in Australia to address problems associated with news. This includes through two ongoing parliamentary enquiries: one by the ACCC focused on news and digital platforms, and a second focused on press freedom.

But surely the crisis in trust of the news media is just as urgent as these other issues.

The Australian 2019 Digital News report found just 44% of adults trusted Australian news. And our own 2017 survey of 1000 young Australians aged eight to 16 found just 23% have high levels of trust in news media organisations.

This lack of trust is important to consider since many of the young people who responded to our national survey said they felt passionate about the role news played in their lives.

For instance, a boy in our study, aged 12 from Queensland, said:

Kids need to understand the world around us and not to just get scary news like murders and hurricanes [but] more news about jobs of the future and things that will be more helpful for our age group.

And a girl, 10, from Tasmania said:

[News] helps me understand the world and know what’s going on and how it might affect me and my family and friends.

The way forward

It’s likely young people’s lack of trust in news organisations is closely linked to their lack of representation.

One clear way for news organisations to begin building trust with young people is to start including them in news stories in meaningful ways.

It doesn’t have to be complicated. For example, in the many instances where young people are photographed, but not quoted, they could be asked to give their opinion or relay their experience.

News organisations could also direct resources to undertake research about stories involving young people. They could build connections with youth-focused organisations who are well connected to young people, familiar with their experiences and with current research.

And they could track who they include as sources, experts and witnesses (considering gender, age range, race and ethnicity) to support organisational reflection on representation and bias.

This will take time and resources, but it seems prudent at a time when news organisations are trying to rebuild the public’s confidence in news integrity and support their own future viability.![]()

Tanya Notley is a senior lecturer in digital media at Western Sydney University and Michael Dezuanni is an associate professor in the creative industries faculty at Queensland University of Technology.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

I’m delighted to hear that young people are smart enough to distrust mainstream media. Since it is principally a vehicle for capitalist propaganda, any relationship “the news” might have to the truth is surely coincidental.

I’d distrust a piece such as this that tries to draw a link between the rate at which people are quoted and their ‘trust’ in the media. The writers didn’t bother to examine how such a link might be provably made and, as a comparison, didn’t bother to check how many times ‘working people’ were quoted and whether they trust the mainstream media.

Our maonstream media is complete crap. The survey result is only reflecting young peoples good judgement.

I find myself wondering how much of that 1% figure is left if Greta Thunberg’s media appearances are removed from it.