Australia’s human rights watchdog has raised concerns about child safety with senior Jehovah’s Witnesses leaders, as the secretive sect faces scrutiny over its handling of sexual abuse claims.

INQ can reveal that Australian Human Rights Commissioner Edward Santow met with senior leaders in the organisation in April to discuss religious freedom and concerns it had been made aware of regarding child safety.

The meeting came after abuse victims appealed to the commission to investigate the group’s practices.

But a spokesperson for Santow played down the meeting, saying it doesn’t have the power to investigate claims of child abuse.

“The commission is committed to protecting the rights of children in all contexts. The rights of the child do not stop at the doors of any religious or other institutions,” a statement said.

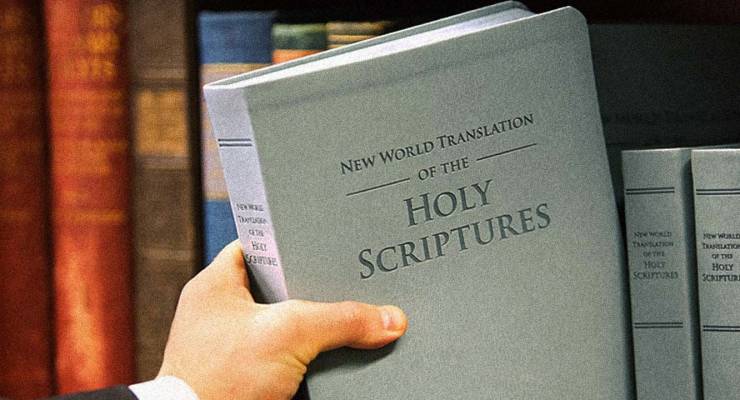

A spokesperson for the Jehovah’s Witnesses Australasia declined to respond to questions about the meeting or concerns of child safety. Instead he referred to a recent article in The Watchtower magazine denouncing child sexual abuse.

Advocates against sexual abuse within the secretive religious group say they are disappointed that the commission hasn’t taken further steps to address what it says are dangerous and discriminatory practices inside the organisation.

“You would think the Human Rights Commission would take a strong stance against these types of issues, but they haven’t,” said Lara Kaput, a spokesperson for victim advocacy group Say Sorry.

“They need to take action where human rights are being abused.”

The Human Rights Commission in its current design cannot take organisations to court in relation to human rights abuse issues. But it can investigate complaints of abuse and develop policy to promote the safety of children. There is currently no public body assigned to regulate religious groups on behalf of children.

The royal commission found that children inside the Jehovah’s Witnesses were not safe from the risk of abuse.

“We do not consider the Jehovah’s Witness organisation to be an organisation which responds adequately to child sexual abuse,” the commission found. “We do not believe that children are adequately protected from the risk of sexual abuse.”

It said the organisation still relied on “outdated policies and practices” that left “perpetrators of child sexual abuse at large in the organisation and the community”.

One practice that was singled out was shunning, where Jehovah’s Witnesses are warned against associating, fraternising or conversing with a person who has chosen to disassociate from the Jehovah’s Witnesses. The commission found the practice prevented child sexual abuse being reported.

“Since a survivor’s entire family and social networks is likely to comprise members of the Jehovah’s Witness organisation, a survivor of child sexual abuse may therefore be faced with the impossible choice between staying in an organisation which is protective of their abuser in order to retain their social and familial network and leaving the organisation and losing that entire network as a result,” it found.

Say Sorry says it wants the Human Rights Commission and other authorities to conduct a full investigation into policies like shunning, which they say are designed to cover up allegations of abuse.

“The Jehovah’s Witnesses haven’t changed their practice of shunning,” Kaput said. “We expect a body like the Human Rights Commission to have a voice on behalf of our children who are being abused.”

Last week INQ reported that a body representing the Jehovah’s Witnesses in Australia had written to all elders in the organisation ordering them to destroy confidential records, including notes taken by elders investigating child sexual abuse, in an instruction that has enraged survivors of abuse inside the secretive Christian sect.

In a letter obtained by INQ dated August 28, a body called the Christian Congregation of Jehovah’s Witnesses (Australasia) instructs elders to destroy so-called judicial hearing records and certain congregation notes.

A spokesperson for the Jehovah’s Witnesses declined to answer questions about the letter on Monday, but said in a statement that records relating to child abuse were “retained in harmony with all legal requirements”.

But during a 2015 hearing, the royal commission heard that it was normal practice for the Jehovah’s Witnesses to destroy notes about child sexual abuse allegations.

Jehovah’s Witnesses elder Max Horley said at the time he destroyed notes from a meeting about a particular sexual abuse case despite it being of “very serious nature”. He also told Justice Peter McClellan he would have destroyed any notes about the incident to protect the congregation and individuals involved.

“That’s our practice,” he said.

Do you have information about this story that you’d like to share? Get in touch: gwilkins@crikey.com.au or confidentially here.

Crikey encourages robust conversations on our website. However, we’re a small team, so sometimes we have to reluctantly turn comments off due to legal risk. Thanks for your understanding and in the meantime, have a read of our moderation guidelines.