Australia’s services industry is booming. But the transition away from traditional industries (manufacturing etc) is making some people extremely nervous. The old good jobs are going, they say.

This idea is the prime focus of a 2018 book by Jennifer Rayner, titled Blue Collar Frayed. Rayner argues: “For blue-collar blokes, work has a meaning and social context that simply isn’t found in many of the other jobs our economy is now creating. However incorrectly, teaching and caring are seen as lacking expertise or art, belonging to the domestic realm of women’s work. Retail and hospitality is what your kids do for video game money, not serious work for grown-ups. Driving is respectable enough but there’s no finished product to stand around at the end of the day, no bit of work that testifies to your skills.”

I’m a fan of Rayner’s other work but this is a patronising depiction of male rigidity. It’s also wrong. A simple example is professional kitchens — the hospitality sector she derides. Anyone who has worked in kitchens, or even just read Anthony Bourdain, knows they drip with testosterone and pride. Men take pride in all sorts of jobs.

But Rayner is on to something more generally: the jobs our economy is now creating could be a hell of a lot better.

What is a ‘good’ job?

Don’t get confused. Those manufacturing jobs were not good because they were in the manufacturing sector. Manufacturing was once a horror show. After all, its dark satanic mills were what inspired Marx to try to tear down all of capitalism. But what made those bad, dark, dangerous jobs so good was a long and persistent effort to improve them. If we fail to learn this lesson we will ruin the quality of work for everyone.

If we want great jobs, effort must not be directed at trying to resurrect dying industries in which China, Bangladesh and Vietnam outcompete us. Effort needs to be directed at making service jobs into good jobs.

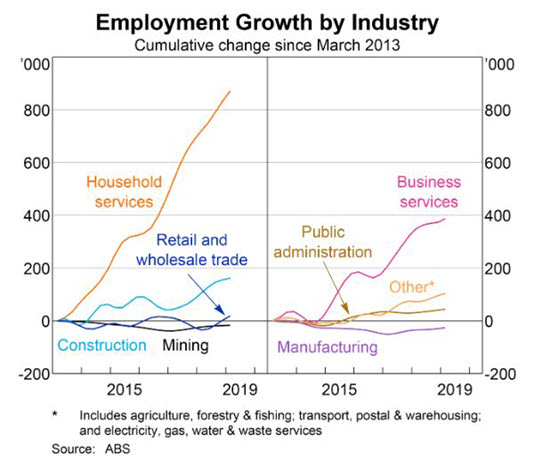

In the chart above, there are two major classes of jobs that are booming. You have business services, which consists mostly of lawyers and consultants and IT people. Those are terrific jobs, safe and well-paid and with career progression. Jobs you’re proud if your kids get into. We can be happy that sector is booming. We don’t need to worry too much about those jobs.

The other kind of service job is household services. This includes doctors, nurses, and teachers, but it also includes jobs like Uber Eats drivers and the kind of franchise workers that are paid full rate on the books but then forced to hand back part of their pay. Not all service sector jobs are precarious, but (almost all) precarious jobs are in the service sector.

How to make bad jobs good

The market, let’s face it, is not up to this task. Business will always offer next to nothing to poorly-educated desperate people without options, and the supply of such people will generally be sufficient that next to nothing will be minimum wage if market forces are left alone.

In the past, unions were instrumental in making bad jobs good. But union membership is in major decline. Australia’s workforce is now just 13.9% unionised (2016 data) down from 35% in 1994. And the unions are most represented in big industries with good conditions, not in the precarious industries. Education and training is 35% unionised, accommodation and food services is 2.4% unionised.

Successive federal governments have made life hard for unions, while unions have also calcified, serving their existing members rather than urgently trying to organise new industries. High-profile corruption cases have undermined unions’ public image in Australia, but the decline of unions is a global phenomenon.

It’s a tough ask to imagine a resurgence of traditional unions. Organising a big factory where all the workers are in one place is hard. Organising a dispersed workforce of contingent workers who take their orders from an app sounds even harder. However, organising all the workers over again might not be so important this time. The lessons of the union movement’s victories remain embodied in a lot of employment law. The challenge is getting that employment law to apply to precarious jobs.

In that context, it is very much worth keeping an eye on the appeal being launched by an Uber driver with the Fair Work Commission (FWC). Amita Gupta was sacked by Uber Eats for showing up late, and lost her case because she was deemed to be an independent contractor. Gupta claims she was paid the equivalent of $7.85 an hour (well below the minimum wage for employees).

There can be no doubt that this kind of job is inferior to an old-fashioned blue-collar job. But the answer is not in trying to get Gupta a factory job. It’s in making sure our employment law protects her. If the FWC bench rules on appeal that she was an employee, that will be a major step.

Recent comments to an audience of principals at a conference I attended (made by a well known futurist) suggest that lawyers and accountants might well fall off the tree with AI, whereas maintenance and repair is just too tricky for non human intervention.

There’s a world of hurt coming to the labour market in the not too distant future. A paper named ‘The Future of Employment’ from Oxford University has outlined just how serious an impact AI will have. Its appendix lists 702 job categories and the probability of their disappearance due to computerisation. 171 categories are listed above 90 percent.

Andrew Yang, US Democratic candidate talks about this at length in a very interesting interview with Joe Rogan on YouTube. He also supports a universal wage concept which he calls “the freedom dividend”. Well worth a listen.

Hoping for the government to do that benevolently doesn’t seem easier or faster than organizing atomized service workers. Why would they ever do that without pressure from an organized movement?

Why do ‘China, Bangladesh and Vietnam outcompete us’ in manufacturing? Cheap labour. Global inequality delivers losers in both rich and poor nations.