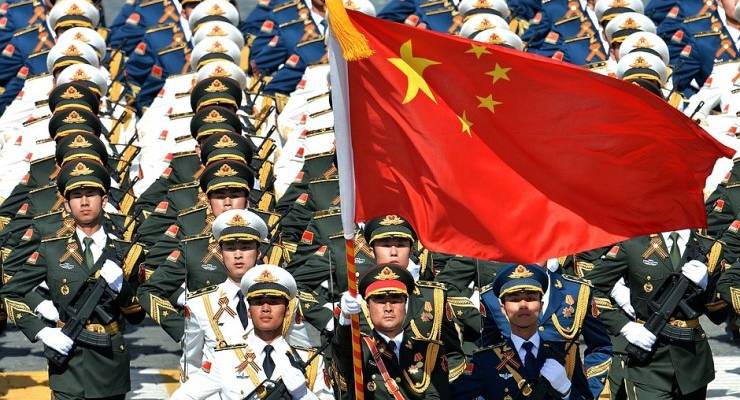

The 70th anniversary of the founding of modern China passed with an impressive (i.e. terrifying) old-school military parade before the balcony on which Mao appeared in 1949. The spectacle was no doubt intended for the world. But it was also tilted more than a little at Donald Trump, the would-be strongman who had insisted on a July 4 parade, and is now facing impeachment — or, to put it in Mandarin, a purging.

This was the moment that China announced to the world that it could no longer be taken merely as an economic powerhouse under the thumb of US unipolar dominance, but as an emerging global military power in its own right; switching to a faster track of arms production and eventual parity.

In the Anglosphere right, the anniversary produced the usual response to any Chinese achievement: they went into conniptions and ran around in circles. Six months ago, Xi Jinping affirmed his own cult of personality and restated Marxism-Leninism as the basis for Chinese development, at which point everyone started brushing off their aged copies of various collected works to see what China would do next.

This anniversary produced the equal and opposite reaction. According to many — Greg Sheridan and Henry Ergas were the local representatives — China was a totalitarian state controlling every aspect of its citizens’ lives. But, they said, the rule of the Chinese Communist Party had nothing to do with the country’s galloping success over several decades, which was due either to the generic East Asian model, or just dumb luck.

It’s a pretty funny totalitarianism which has nothing to do with the economic life of its citizens. The conclusion is, of course, bunkum. Some on the naive right, the chino-pearls-Hayek-fanboy squad, are angered by the stubborn refusal of China to correspond to the idea that demands for political freedom shadow economic freedom. China has shown the opposite: give people a chance to improve their lives within a fairly stable framework, and such rewards will actively defer demands for political pluralism for decades upon decades.

For them, China essentially refutes a philosophy they have based their life on.

For those who cherished the idea that the West had all the answers, China’s surge has been particularly upsetting. Its post-1978 rise was achieved without injection of foreign capital. The “East Asian miracle” that benefited other nations was based on billions in US capital given as a political tool to offer a post-colonial alternative to socialism. When that tap was turned off, some small states — Singapore, South Korea — fared well, others less so. Thailand and Indonesia have been relatively stagnant for decades, remaining rural and semi-underdeveloped, while China has entirely reconstructed itself.

The reason for that has been Marxism. Mao was unquestionably a Marxist revolutionary, though his regime, to 1976, was mostly un-Marxist in its ideal of a collective will to “leap forward” followed by the cultural revolution’s commitment to the nation-as-commune. When Marxism really arrived in China with Deng Xiaoping’s leadership it did so in the form it had taken in the USSR’s 1921 New Economic Policy — a sector of the private market was retained, special economic areas were introduced, but one-party rule was maintained.

The importance of having a mixed economy, with 60% in state hands, was that funds could be steered towards infrastructure, and the country could bootstrap itself and build an urban working and middle class. Compare India, which has lurched from village socialism to neoliberalism, resulting in a “missing middle” between a rich elite, a residual working/rural poverty, and absolute poverty. Or compare Nigeria, which never managed to free itself from the capitalist world-system, with whole regions being as poor as they were at decolonisation. Or for that matter compare the Anglosphere West, which has talked its way into stagnation by allowing capital to starve demand by crushing wages and evading taxes.

For the Chinese, the goal of socialism remains. But it is not the slightly hippy, weave in the morning, seminars in the afternoon type thing of the 19th century. The CCP is clearly preparing for an era of nationalist post-capitalism, one in which automation and cybernation reduce capitalist accumulation in key sectors to a level that makes private reinvestment impossible. At that point the nation acts like a unit, with a retained but limited private sector, surrounded by a system of universal basic income and universal basic services.

The economy is not centrally planned, but steered by real-time qualitative feedback between production units. As far as one can see, the purpose of the country’s new universal social credit system is to lay the basis for a post-wages form of social control and reward.

The great difference in Chinese transitional capitalism/proto-socialism is that it is conceived in national terms and anticipates future war — with India, Russia or the US. Hence patriotism and military expansion accompany the steady revolutionisation of production — robots, 3D printing manufacture — applied with a focused rapidity that the West cannot, at the moment, match.

If the right is scared for what this does to its pathetic fairytales of history and the West, they should be. And as the cannons and hypersonic missiles parade by, they shouldn’t be the only ones.

Whilst I oppose the social oppression and repression of the CCP, the fact is that China has raised more people out of poverty in the past 50 years than all the other nations on earth combined. Why is that never mentioned by the critics that hold so dear to the notion of ‘Western Civilisation’?

China has raised nearly as many as many people out of poverty as the U.S and Australia has put into poverty.

Good comment about China but I disagree about Indonesia and Thailand having lagged behind. I lived for several years in Indonesia in the early 1970s and have been back for visits many times since. They have advanced hugely, not only in Java but in the remote regions. Even restless Papua has a highway across its mountains now and widespread electrification of its villages is proceeding. I lived in southern Thailand for two years in the late 1990s and visiting recently I could see a lot of positive changes despite the low level Maly nationalist (not Islamic, nationalist) insurrection. Thai soldiers sat bored at checkpoints around Muslim Malay Yala reading newspapers while cranes rise above the town.

I have no idea how you could characterise somewhere still undergoing electrification as not ‘lagging behind’. How is that not literally over a century behind?

It is a long way behind what we are accustomed to. Whether you call it lagging behind depends on your reference point. There is development compared with what it was, and compared with other places in the same region. It’s getting facilities it never had before. When I was living in rural Java in the early 70s villages there didn’t have electricity and in the cities it was limited and unreliable. Even in China today the great rural hinterland is very unlike the shining cities. By the way, when I was a kid on the farm in WA in the 1950s we didn’t have electricity. When we got it, it was via a diesel powered generator and a bank of batteries. I think the grid was extended that far only in the 1970s.

Yes. We didn’t have sewerage in Laverton, Melbourne in early 80’s. We were still getting the “night carts”.

“Lagging Behind” is a relative concept.

Yes, lag does tend to be relative to a reference point. Not sure why you point this out? Seems like that means they are lagging behind?

Rais

China was way behind Indonesia decades ago. It is so far ahead of it now that the latter neoliberal kleptocracy disappears in the rear view mirror. A highway? Electrification? China has built 200 cities, key major centres linked by maglev 400km/h trains. Djakartas main station is still the one the Dutch built, into which ancient carriages wheeze in. Development? Please.

It would be good if other Crikey writers followed your example in responding to comments Guy. Thanks for that. In support of your argument I have to admit: GDP per capita past and projected, Wikipedia: 1989 China $409, Indonesia $697. 1999 China $872, Indonesia $830. 2009 China $3838, Indonesia $2465. 2019 projected China $$10153, Indonesia $4319. So in the absence of China, Indonesia’s growth would look very good but it is, as you say, far outpaced by China. In support of my argument, the other great Asian power India’s GDP per capita in 1989 was about half that of Indonesia and in 2019 it still is.

It is a remarkable acheivement and the country has shown amazing restraint toward Hong Kong. The grinding halt Australia has come to which by my reckonoing seemed to have happened in the time of Howard, sits in stark contrast to the development of China. The last 7 years have been worse…we’ve actually gone backwards in many regards.

What seems to have disappeared from Australia and possibly other Western countries is a sense of national vision and civic pride. We no longer do things to build the nation. We only do the things that are of benefit to the sliver of the population that consists of the most wealthy. No better illustration of this can be found in the very first and so far only accomplishment of the current Morrison government. When they won the last election, did they follow the victory with some grand plan of accomplishment that would make Australia a better place of which we could all be proud? No. They did the only thing that really matters to them. They cut taxes, primarily for the ultra wealthy.

It wasn’t always this way. Drive through any of the grand old gold towns of central Victoria, for example, and you will see magnificent architecture both public and private that serves as monument to the time and to the dreams of the people who built it. Admittedly, their vision was far from perfect. It was racist and exploitative and built on the myth of the colonial white male who conquers the wilderness with no thought of what he is destroying in the process. In other words, it was just as flawed as the vision driving today’s China. For all of that, it gave the country a sense of purpose and direction.

We’d never build buildings like that today.

Morrison, Trump and Johnson are the same in one respect. They embrace and make a virtue of mediocrity. They lack the intelligence and the imagination to inspire. As it is today, so shall it always be.

China will devour them, with us in their wake.

To neoliberalism there is no nation, state or society – just a game called ‘the market’ where we all play as competing individuals. To the neoliberalistas this is not a failure to address the health and progress of the nation/overall society, but a deliberate refusal to believe that these things even exist (cf Margaret Thatcher: ‘There is no such thing as society’).

“The 70th anniversary of the founding of modern China passed with an impressive (i.e. terrifying) old-school military parade..”

The Mad As Hell producers will be so pleased to have some updated video to use.