A long-term shift to a more female-oriented workforce in Australia has accelerated in recent years, with Australia’s jobs boom heavily favouring women as female-dominated service industries expand rapidly.

In the year to August, according to ABS data, 1.4 jobs for women were created for every one for a male, with over 182,000 new jobs taken by women compared to less than 130,000 jobs for men. That’s a significant acceleration in female job creation compared to the five years to August 2019, during which 713,000 female jobs were created compared to 573,000 for men.

That, in turn, was a faster rate of female job creation than the five years to 2014. In February this year, the number of employed women topped 6 million, and they now make up 47% of the workforce, up from 46% in 2014.

And while women continue to dominate part-time job creation, they increasingly dominate full-time job creation. The traditional male dominance of full-time jobs switched gears in the three years to August 2019, with new full-time jobs roughly equally split between men and women, 326,000 to 316,000. In the year to August, however, 116,000 new full-time jobs went to women compared to 70,000 men.

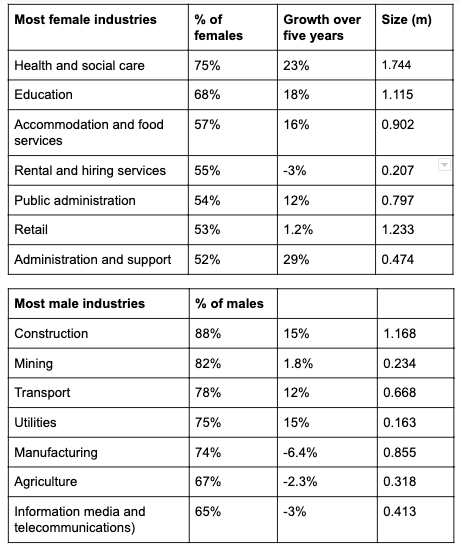

Why? Our five fastest-growing industries are administration and support, health and social care, education, accommodation and food services and construction. The first four of those are either predominantly or, in the case of health and social care and education, heavily female.

Only construction is male dominated, and construction employment is already contracting as the residential property boom disappears in the rear-view mirror.

The list of slow-growing or shrinking industries is topped by manufacturing, a heavily male industry; followed by information media and telecommunications, another male-dominated sector. Utilities has been growing fast, but is relatively small (like mining, which has been static); only transport, 78% male, is a major and fast-growing sector.

Professional services, which is 59% male, also grew strongly — 24% over five years. Rental and hiring services and retail, both slow-growing or shrinking sectors, are predominantly but not heavily female.

Our ageing population is a major driver of the expansion of our most female industry: health and social care. But the Turnbull government’s embrace of Labor’s spending plans for health and education turbocharged this. Within some sub-sectors, the phenomenon is even stronger.

Preschool and school education, which at over 660,000 employees is bigger than most industries, is 73% female and grew by 25% in the five years to 2019. The residential care workforce, which is 80% female and has over a quarter of a million workers, grew 26%.

The outlook for male-dominated industries, however, is bleak. Manufacturing has collapsed in recent years; its current level of 855,000 is its lowest ever. (It isn’t the closure of the car manufacturing industry; the transport equipment manufacturing sub-sector has been stable or growing in the last couple of years.)

The cyclical nature of construction means it will eventually bounce back but it is unlikely to provide the kind of strong growth of recent years again until the 2020s. Mining is too small and is unlikely to see strong growth again given the rising level of automation; male-dominated agriculture is small and getting smaller as an employer.

This shift in jobs growth has flow-on effects. Health and social care and education are the two sectors with the strongest wages growth in recent years. But in construction — despite the Coalition’s hysteria about the “militant” CFMMEU — strong growth hasn’t translated into wage rises. Women aren’t merely getting more jobs, they’re getting bigger pay rises than men.

This feminisation of the workforce is a long-term story, driven by an end to formal discrimination against women, rising house prices that demand two incomes, more access to child care and the switch in western economies to service industries traditionally dominated by women (and traditionally underpaid and undervalued).

The concomitant decline in traditional blue collar jobs in western economies has been blamed for the alienation of older blue collar white males and the rise of populism, though the benefits for society of women having greater opportunity and economic empowerment (and why men won’t enter certain professions) have received less attention.

At a time of relatively high employment, an acceleration in the level of job creation for women may have no side effects. In a prolonged construction downturn and rising unemployment, however, a pivot to a female-dominated workforce might prompt more of the kind of alienation and bitterness that marks sectors of the electorate here and in other western countries, especially if men remain reluctant to enter service industries.

My favourite negative correlation example – PISA Maths literacy in 2000 was 533, in 2015 it had dropped 37 points to 496. Simultaneously, the number of female high school teachers has increased from about 50% to 68% (or more). The correlation is almost a perfect -1. And whilst there’s no study determining whether the two relationships have causation, perhaps there should be one…

Or maybe its because participation in maths has been dropping over that same time period. Because studying maths and your mathematics ability are probably causally related in someway, you know maybe!

This was obviously a deliberately sexist comment to get a response but that doesn’t mean its not worth responding too. If you’re sexist, you will always find a way to put down women.

My other comment on this article is women are working more because they want to – so they have their own money, independence, sense of agency and are not dependent on a partners income.

With the decrease in demand for brawn and belligerence, perhaps we should be selecting for female babies. A higher proportion of fertile Australians might solve our population crisis too.

Population crisis in Australia ?..l like your satire..Any female with half a brain would be thinking more than twice about breeding..

How does one define a “job for a woman”as opposed to a “job for a man”?

That employment growth is stronger in jobs where female participation has, historically, been higher, doesn’t mean they are jobs for women. More likely, male job seekers are buying into the same stereotype as you Bernard, and not seeking opportunities in those industries. We can only hope, for their own sake and for the sake of the community and the broader economy, that male job seekers will wake up to this and develop skills which make them employable in the areas with greater employment growth.

I’d also note that, in the past, some parts of manufacturing were dominated by female employment, they being textiles, clothing and footwear. However, those industries were hollowed out and destroyed by unilateral tariff reductions, long ago. The higher dollar (of the last decade) and higher energy are now eating away at the remaining areas of manufacturing. Of course, one shouldn’t forget vehicle manufacturing, the demise of which can be laid squarely at the feet of the current Coalition Government and its indifference to a more diverse economy.

A lot of the jobs in health-care are low-paid, hard work and thankless. i am thinking specifically of aged care. Many men regard this type of work as beneath them somehow, especially when compared with the money that can be made in some manufacturing, but it is a growing area and needs serious industrial action to improve wages and conditions. I hold out little hope that the Royal Commission will do anything to address this.

Quite. “Traditionally underpaid and undervalued”, and currently, still underpaid and undervalued.

Goodness mary your words sound rather like someone who’s never worked in manufacturing. Low paid, hard work and thankless to which I’d add mind numbingly dull. Also women were long preferred for fine assembly work and probably still are.

I like your lines Bernard about jobs created for women. Better be careful some self important agency doesn’t tick you off. There’s another article here today about a long named Peruvian agency fining a restaurant for having payer and guest menus which of course they can only interpret as men’s and women’s.