The widely reported battle between Djab Wurrung people and the Victorian state government over the construction of a highway in western Victoria has given insight into the failure of established practices, which require the government to seek the free, prior and informed consent of the Indigenous people whose land will be impacted upon.

The plan is to duplicate the Western Highway to make a freeway near Ararat, to save motorists about two minutes driving time between Melbourne and Adelaide. This will see the destruction of more than 3000 trees thought to be up to 800 years old — including birthing trees, which have hosted the delivery of an estimated 10,000 Djab Wurrung babies in their hollow trunks, and have ties to 56 family groups.

For months, the traditional owners of this land have faced a battle on multiple fronts to be heard on this issue.

The first battle: misrepresentation

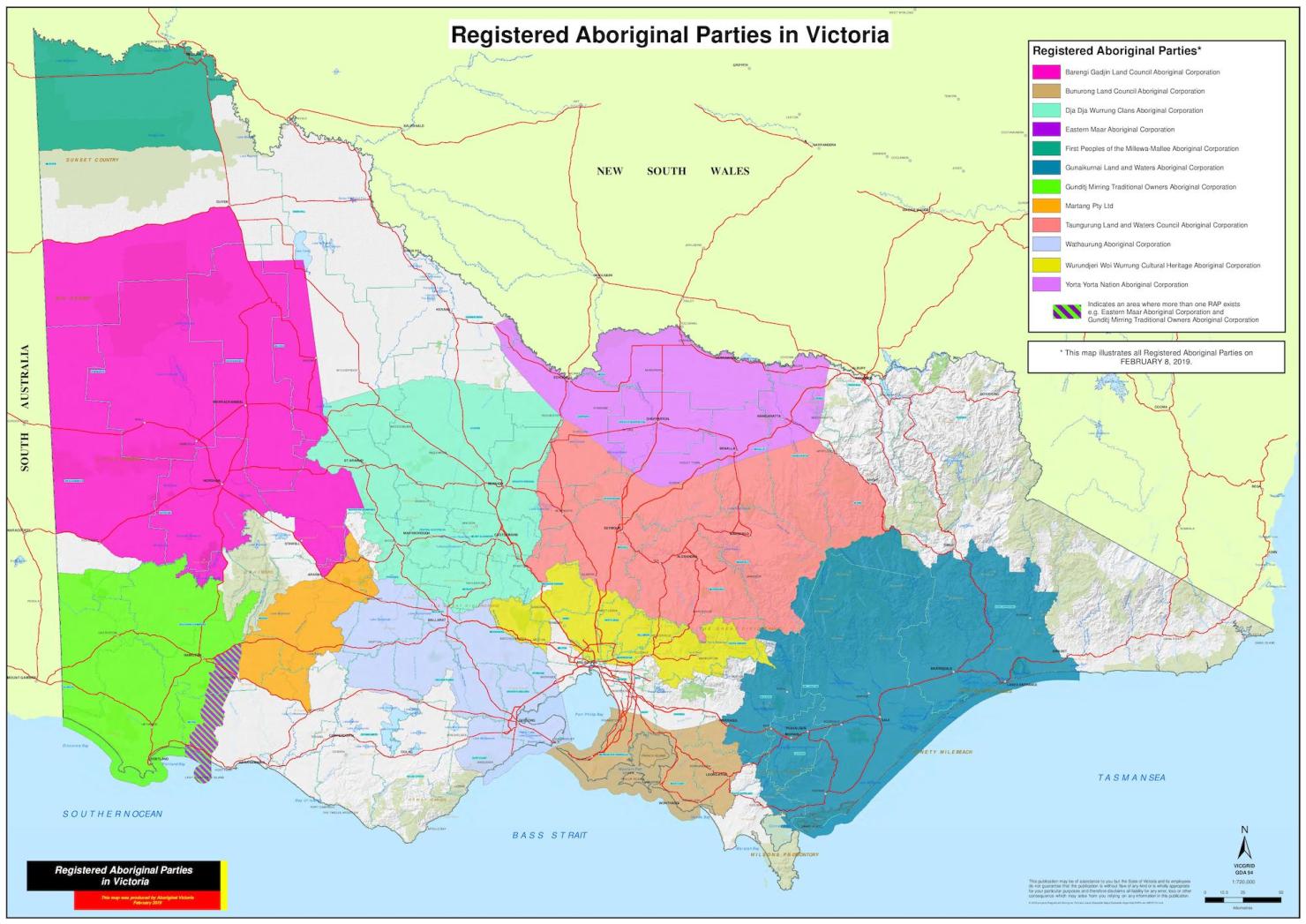

Instead of having a direct line to decision-makers, Djab Wurrung people have been represented by two Registered Aboriginal Parties (RAPs) — Eastern Maar and Martang — which are appointed by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council (VAHC) to officially oversee areas of land.

RAPs are tasked with developing a cultural heritage management plan, and identifying areas that require cultural heritage mapping before any development can take place.

Over the last 12 years, only 12 RAPs have been created for the 38 Aboriginal nations across Victoria. The VAHC is meant to be independent, but the board is appointed by the Victorian minister for Aboriginal affairs, who then determines whether an applicant gets RAP status.

There’s an alarming lack of transparency and due diligence around the VAHC’s decision-making process to accept or reject applications for RAP status, which is concerning considering that achieving RAP status is big business. Aboriginal Heritage Centre-endorsed RAPs get millions in government funding.

Martang — whose jurisdiction covers the highway expansion — was first appointed RAP status in 2007. At the time, and for years thereafter, it was a closed shop — a private company consisting of only two directors and four members, all from the same family. Applications by other members to join were rejected for years.

During all of this time, Martang had the authority to make land-use decisions over Djab Wurrung country — approving, in 2013, the Western Highway extension plan. That plan — which has not been made publicly available, and Department of Premier and Cabinet has refused to release under FOI for Inq — failed to identify the now-famous and sacred Djab Wurrung trees adjacent to the Western Highway as culturally significant.

Separately, in 2011, a second RAP, Eastern Maar, would begin native title claims over a large area of south-west Victoria after being recognised, along with Gunditjmara peoples, over a smaller patch. This extension would overlap with Martang’s area, sparking a public war of words between the groups attempting to discredit each other’s validity. In 2012, Eastern Maar member Geoff Clark stated that Martang exemplifies how “nepotism and cronyism operates in Aboriginal Affairs”. Clark noted that one of the four members — Tim Chatfield — worked as both an adviser to the premier and a chairperson on the VAHC. The body that approves RAPs.

In 2014, Martang and the Victorian government struck a deal that delivered Martang hundreds of hectares of land and an initial $90,000 instalment to assist with planning for the new road. Since then over $1 million has been dished out to the group, and the most recent deal includes hundreds of thousands of dollars to conserve a separate patch of land as part of VicRoads’ obligation to offset the Western Highway expansion.

Jump forward a few years, and public pressure over the Djab Wurrung protests saw VicRoads extraordinarily claim both groups had approved the project (Eastern Marr denies this happened).

Following the confusion and the battle over native title, Martang was deregistered as a RAP in August this year when, for still unexplained reasons, it ceased to be a body corporate.

In this vacuum (with considerable assets now “up for grabs”) Eastern Marr has since stepped up as a defacto second RAP, and, after the state government promised to save a handful of sacred trees from destruction, eventually did give the tick of approval in May this year to allow the Western Highway expansion to proceed anyway.

With Martang gone, Eastern Maar has angled to increase its jurisdiction to cover Djab Wurrung country and beyond. If successful, that would mean it has the authority to approve land use and development decisions over no less than four nations in western Victoria.

But still. Neither of these groups represent Djab Wurrung people.

The second battle: the alternate route

Despite the side-show going on between Martang and Eastern Maar, I, along with other Djab Wurrung people, have been championing our own solution to the highway expansion: an alternate route. The alternative plan would take the highway further north, closer to a power line easement, and save a number of trees. It has the support of local landowners, Djab Wurrung elders and a former VicRoads engineer who detailed in an affidavit that the alternate route would save the government around $20 million.

After months of on-site protest, demanding a say in the matter, we were granted a mediation with Major Roads on October 3. We sat in three separate rooms, as lawyers darted between the parties and hashed out a long-awaited deal.

We agreed to allow 2.5 kilometres of the 12 kilometre expansion to continue, stopping short at the point where the alternate route would divert — with the caveat that no heavy machinery would be used. Documents seen by Inq state that only a hand shovel may be used for excavation works. The government agreed and arranged to meet for part two of negotiations on December 1.

However a week later, the truce was broken when it was alleged Major Roads moved in with heavy machinery. Major Roads has provided Inq with a statement saying that “MRPV is conducting works on the Project in accordance with the agreement”.

This process, and the lack of understanding about how to work with traditional owners, has meant that the highway project is two years behind schedule and has cost the government almost $40 million more than it should.

Lidia Thorpe is a Djab Wurrung traditional owner and the former Victorian state MP for Northcote. Additional reporting by Chris Woods.

Yep, best wishes from me on this. Despairing that a ‘friendly’ government is being so asinine about something where an alternative solution has been found that won’t cost any more.

My experience is that main roads type departments, being full of engineers, are a little hard headed and inflexible in their thinking (knowing better than everyone else) and they don’t take kindly to other people pointing out that their solution rides roughshod over human beings.

When governments get a bug up their arse over a Big Project, logic, fairness and especially truth go out the window. (Look at Snowy Mark Two). You’d expect the Andrews government would be better than this, but then a Big Project must never be seen to be stopped by small scale protests; there’s a principle at stake, and large governments don’t like small groups telling them off. Keep up the good work; hold them to account.

What BS — Who uses hand shovels for excavation works these days ? Even small holes on suburban blocks are dug by small bobcats.

You really picked up the essence of this story, Desmond.